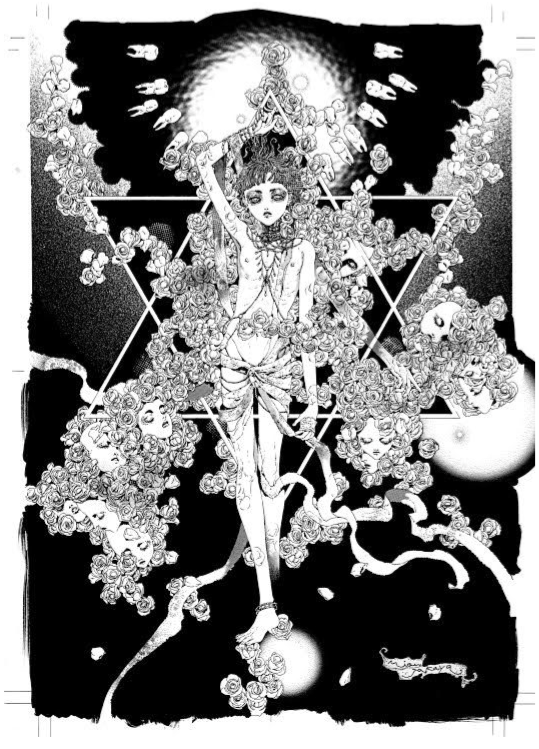

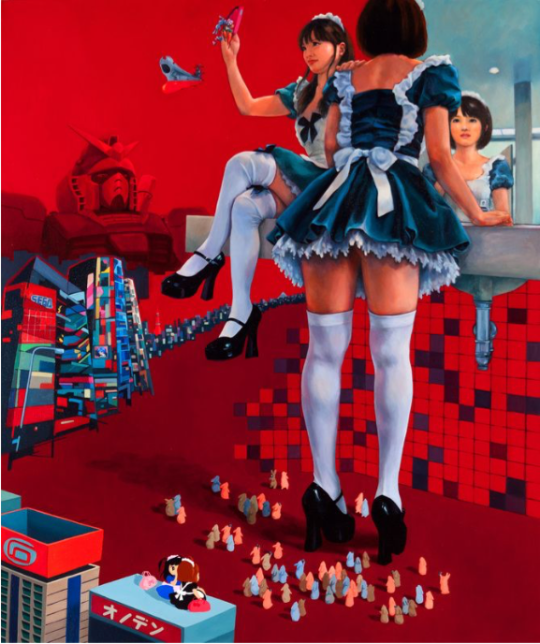

Takaya Miou, Love Thyself. Courtesy of the Honolulu Museum of Art.

The Honolulu Museum of Art is giving a facelift (and some goth eyeliner) to the stale, stuffy image of “High Art.” With one of the largest collections of Asian art in these Eurocentric United States, the HoMA isn’t willing to rest with the traditional canon that dominates many mainland museums. Rather, they are pushing boundaries to expand the notion of art to everything from erotica to Tokyo Street fashion.

Now on view through January 15, 2017, they present Visions of Gothic Angels: Japanese Manga by Takaya Miou, the first in a series of Manga exhibits. Last week, Sarah and Griff were lucky enough to sit down with Stephen Salel, Curator of Japanese Art for the museum’s Robert F. Lange Foundation, to talk about the exhibit.

“…as a museum, we feel a bit of a responsibility to help emerging manga artists.”

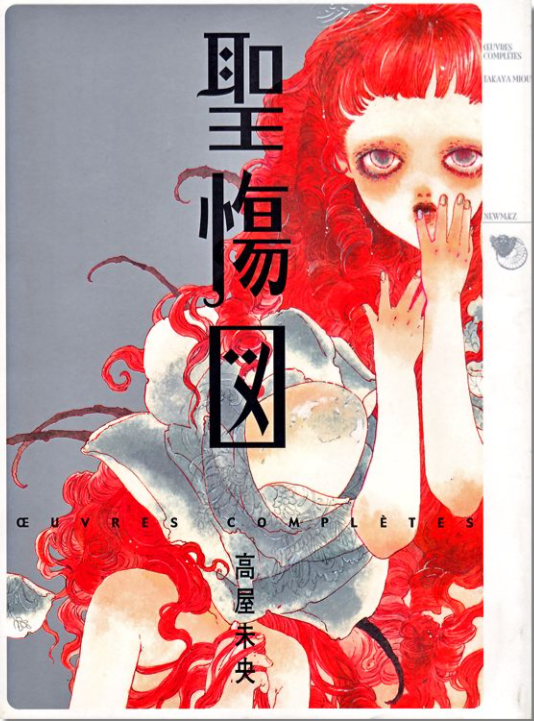

Takaya Miou, Map of Sacred Pain (Seisho zu)

Stephen: This exhibition, Visions of Gothic Angels: Japanese Manga by Takaya Miou, is the first of what we envision to be a ten year project focusing on contemporary Japanese manga. Our museum in the past few years has been trying to break free from the kind of stereotypical image of an art museum, that being sort of conservative and crusty and focusing on the classic art from Western Europe. In addition, even in the field of Asian art we’re really trying to look at things that happened in the 20th Century and the 21st Century. The artists who we are looking at for this series are not your conventional internationally famous manga or anime artists. At one time, we were considering people like that but …as a museum, we feel a bit of a responsibility to help emerging manga artists.

Takaya Miou lives in Nagoya City in Central Japan. We discovered her work through an English publication on manga published years ago. She’s relatively unknown internationally and even in Japan.

The Apparition by Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, in the Orsay Museum.

She has this fascination with Western art, ironically, artists like the symbolists painters from the 19th Century…and she combines these ideas into her work, which, if you were to classify it is basically “shojo” manga; works depicting young women which is directed towards the young female audience. This is a part of manga that we here at the museum find to be incredibly rich in ideas and will be focusing on it a bit in the coming years.

“We’re going to try to make it as visually dynamic as possible so that you’re literally leaping into Takaya Miou’s world.”

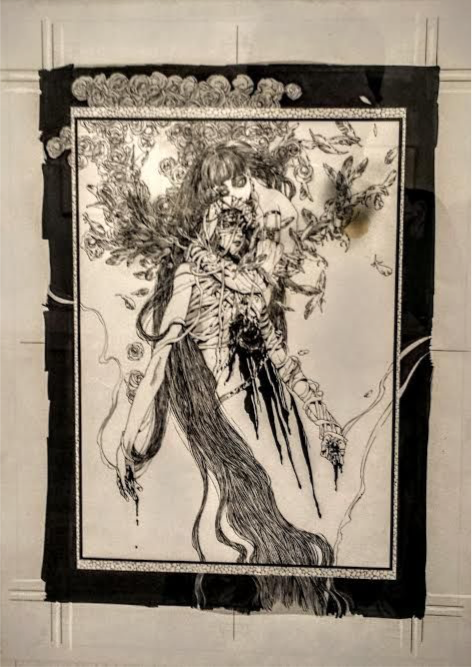

The installation in progress: stark white pages in the process of transforming into living, life-sized manga. Courtesy of the Honolulu Museum of Art

The blank spaces here we’ve reserved for large-scale wall graphics; taking some of her works and blowing them up from floor to ceiling. We really want to make a visually dynamic show here. One of the problems that some exhibitions of Asian art in various museums throughout the world have is that they put something into a small frame and line up the frames on the wall in a very static way and it doesn’t convey the kind of energy that you’d hope for. We’re going to try to make [the show] as visually dynamic as possible so that you’re literally leaping into Takaya Miou’s world.

Takaya Miou, Higher Love (Angeliseraphim). Courtesy of the Honolulu Museum of Art.

Visually, it’s quite an interesting survey of what she’s done and the sort of meticulous detail-oriented approach that she takes to her imagery. It’s not the kind of artwork that people think of when you usually say manga. I think people equate manga to cartooning or something like that, but Takaya, along with many other Japanese manga artists have a very mature, sophisticated approach to the work and, from an art-historical perspective, I like to think of it as a modern and contemporary extension of what this museum is famous for, which is ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

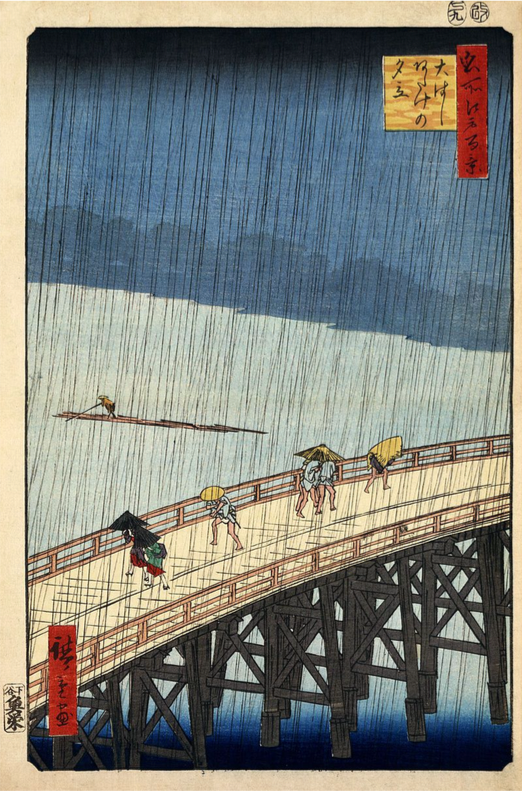

Utagawa Hiroshige, Sudden Shower at Shin-Ohashi Bridge

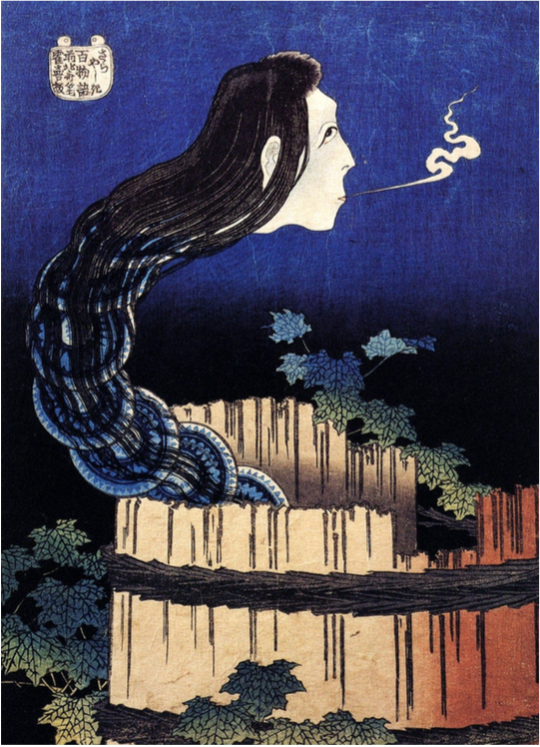

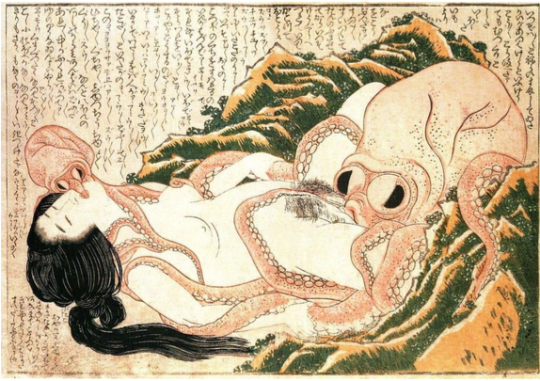

Artists like Hiroshge and Katsushika Hokusai are some of the most famous examples of that kind of Japanese art. Not many people realize that Hokusai is also famous for coining the word ‘manga’ for his sketchbooks and if you look at his work or even other artists throughout the centuries, this idea of a story-based approach to figurative art, one that’s often kind of whimsical or dramatic, definitely leads up to this kind of contemporary work in a seamless way.

Katsushika Hokusai, Okiku

“We’re trying to incorporate quite a bit of technology into exhibitions like this…it brings a lot more ideas in interesting ways to the conversation.”

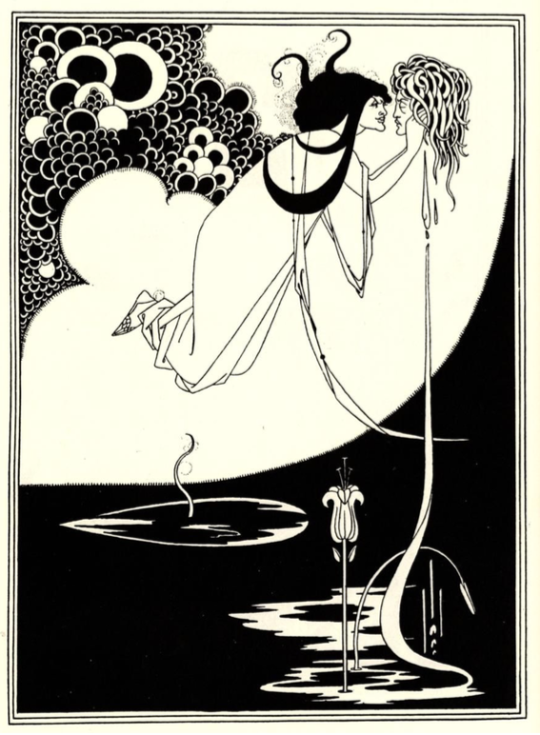

Sarah: I know she references Western art a lot. Are there any specific pieces from the Western perspective that you think are especially referential? We know she’s influenced by Beardsley in her line drawings…

Stephen: One of the most famous works that Beardsley did was a series of images based on Salome by Oscar Wilde. And this is actually a piece that’s entitled “Salome” and if you look at it, apparently the woman here is Salome herself and she is embracing a figure who is apparently King Herod. But [Takaya] takes a very unique approach to it.

Takaya Miou, Salome

…we’ll have an ipad where we’ll display Beardsley’s Salome portfolio, and talk a little bit about how both in terms of subject matter and style she’s influenced by him. We’re trying to incorporate quite a bit of technology into exhibitions like this, just because it brings a lot more ideas in interesting ways to the conversation, and also because we’re situated in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and having a website, we can really reach out to an international audience.

The Climax from Aubrey Beardsley’s “Salome” portfolio

Griff: On the note of Beardsley, she seems to reference erotic art a lot, and I know last year you had that show, Modern Love on Japanese erotic art. Beardsley also did erotic art…

Stephen: He did indeed.

Griff: We watched an interview with you on that show, and one of the things that comes up is it would be impossible to have an explicitly erotic art show in Japan.

Stephen: Right.

Griff: And then Beardsley, of course, with his friendship with Oscar Wilde also faced a lot of censorship issues, so do you see an intersection there?

Stephen: Definitely. I think that, with this exhibition here we are gradually trying to pull away from the topic of erotica. Modern Love was the third in a series of exhibitions that dealt with the historical progression of what we call “shunga” (Japanese erotic art) and when we switched to this current series on manga there were some voices in the museum that were saying ‘enough already with the sexuality stuff, let’s focus on other things.’

One of the most iconic works of “Shunga” is Hokusai’s The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife.

We tried to approach those shows in a way that was responsible and mature and intellectually sophisticated. And I think that we achieved that, but ironically, even now that we’ve moved onto another subject…we’ve come to realize that in contemporary Japanese art there is always a certain amount of discussion about the human body and sexuality.”

Takaya Miou, Hellogabalus. Courtesy of the Honolulu Museum of Art.

“Manga that deals with women’s issues are a really thought provoking aspect of the genre.”

Griff: So there seems to be sort of a Western tendency to dismiss Japanese erotic images as misogynistic. But what one of the things that we noticed in our research is that fairly early on in modern manga, especially starting around the late 60s, women started playing a really active role, especially in producing girl’s manga. What would your answer be to somebody who would try to write off erotic manga as misogynistic?

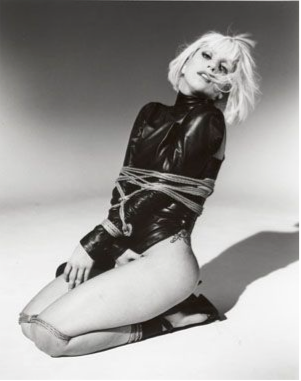

Stephen: Right, well that’s a great question because it’s something that we’ve been very concerned with here from the beginning. Let me start off by saying, about that stereotype; when we were putting together the shunga exhibitions, and particularly the final one, Modern Love, where we had images by photographer Araki Nobuyoshi and artists who have often been criticized by, particularly by Americans, for having very negative attitudes towards women, I took a very consciously neutral approach to the subject matter.

Araki Nobuyoshi, Lady Gaga on her knees 01. Image via Vogtle Contemporary Art

I didn’t want to make any kind of ethical judgments on the subject matter because it’s not my culture and it’s not my time period, except, with the latest show, which dealt with contemporary stuff. But what we were doing with works that were produced back in the 17th and 18th century…it’s a very different cultural context. So we presented the work and simply said, “this is what we believe the artist was trying to communicate, how can we learn to appreciate it?”

“…when Japanese female artists are given an opportunity to talk about their stories and to collaborate together on projects…they really take off.”

Regarding the group of female manga artists who started around the 1960s, I’m happy to say that around the year 2020 we’re hoping to put together an exhibition of their work, or at least work by female manga artist that begin with those pioneers.

Work from Emperor of the Land of the Rising Sun by pioneering manga artist Ryoko Yamagishi

Manga that deals with women’s issues are a really thought provoking aspect of the genre, and one great thing about it is that they deal with topics of the body and sexuality from a female perspective. And that’s pretty radical in my opinion for a country in which women still play a relatively quiet role in government or in daily life. Even though women have gained a lot of civil rights in the past 100 years, there is still the tradition in which women are expected to be focused on family and in playing that sort of stereotypical motherly role. There is a term “good wife, wise mother” that was popular in Japan around the early 20th C and, unfortunately, that sort of old-fashioned attitude about gender still hangs around.

Takaya Miou, Brilliance (Hikari), panel 1

Griff: Yet one thing that struck me was how early and how actively women took charge of their own stories, and it doesn’t jive with a that Western stereotype of the sort of passive Asian woman.

Stephen: Right, exactly. I think that when Japanese female artists are given an opportunity to talk about their stories and to collaborate together on projects like that, they really take off, and that’s what we’ve seen over the past 50 years or so.

“…wherever you look in Christianity, you see that emphasis of the sensuality of the body…in both a sexual way and also in a violent way.”

Saint John Altarpiece by Rogier van der Weyden, in the Gemaldegalerie. Salome, back at it again!

Sarah: As far as the religious iconography, from my understanding she uses it because she likes it aesthetically, is that correct? Or is it a form of social critique?

Stephen: In an interview that she did years ago, she talked about how fascinated she was since childhood with Christian mythology. For example, St. Sebastian is a character that appears in a lot of her work. There is, I believe on that wall over there, an image of a female St. Sebastian. And she talks about it as being this very emotionally evocative image.

Takaya Miou, St. Sebastian. Courtesy of the Honolulu Museum of Art.

There’s violence, there’s also sexuality. And she kind of jokingly says, wherever you look in Christianity you see that emphasis of the sensuality of the body, the physicality of the body, in both a sexual way and also in a violent way. In other words, she’s bringing up some slightly taboo subjects basically about the sado-masochistic tone of some religious art. And I think that as a woman who was not raised in the Christian church and who approaches it from a very distant objective perspective…she feels a certain freedom to make those sorts of comments. And it makes her artwork sometimes kind of challenging. But like I said, our museum nowadays is really interested in displaying work that’s challenging in that way.

St. Sebastian by El Greco, in the Prado National Museum.

“I don’t know if she would feel comfortable being labeled as a feminist, but I feel that she deals a lot of with gender issues and that’s something that we’re very excited about!”

Critiques, social critiques. When I talk in one of the podcasts that will be both on the website and on ipads in the gallery. I talk about the way in which she takes the image of angels and she sort of changes them, appropriates them, in an interesting way. The way that the term angel is really defined in Christianity, it’s a kind of a messenger for God. In other words, sort of a servant to a very clearly male deity. And in her work she takes these winged figures, and they’re often female, and they are often shown in armor or with weaponry, or in some way shown as being very independent and very capable and obviously not just messengers. So in that way she’s really showing them as powerful women. I don’t know if she would feel comfortable being labeled as a feminist but I feel that she deals a lot of with gender issues and that’s something that we’re very excited about.

Harajuku Fashion superstar Minori. Image via www.ibtimes.co.uk

There’s also a connection with what’s going on in the Harajuku fashion movement, I think. There are a lot of contemporary designers and artists in Japan who are looking at the Victorian culture…basically 19th century European fashion and attitudes about the body, and they’re finding it to be really exotic, really glamorous and are reviving it. And Takaya is definitely doing that too. If you look at her work here you will see very clear references to Harajuku fashion and Victorian fashion, and in other works as well you can find that idea of “Gothic Lolita.”

Dress by Harajuku retailer Juliette et Justine (left). Beardsley-esque illustration for Edgar Allan Poe’s Ligia, by Harry Clarke (right).

“a lot of her work comes from dream imagery; it’s very spontaneous, so she doesn’t really overthink her artwork.”

Sarah: Is that specific draw just for the aesthetics or do you think there is something more to it? Why the Baroque and Victorian?

Stephen: I think it goes beyond aesthetics. I think that, in some ways, and I haven’t quite figured this out, Harajuku fashion or references to that culture is a way for contemporary Japanese women to regain a certain power, a certain authority over their bodies and…be sexual beings in a way that doesn’t simply objectify them. I know that’s filled with a ton of contradictions because there is a lot of criticism of Harajuku fashion that talks about how it simultaneously infantilizes them and it also sexualizes them.

Moe Elements of the Floating World I by Hawaii-based artist Yumiko Glover. Via yumikoglover.com

I don’t know how consciously Takaya is doing that. I think a lot of her work comes from dream imagery; it’s very spontaneous, so she doesn’t really overthink her artwork. And that’s why I hesitate to refer to her as a feminist artist or a very overtly political artist. But in having that freedom to think about things, and in the way that she refers to Christian imagery…I think that might be part of what influences her work.

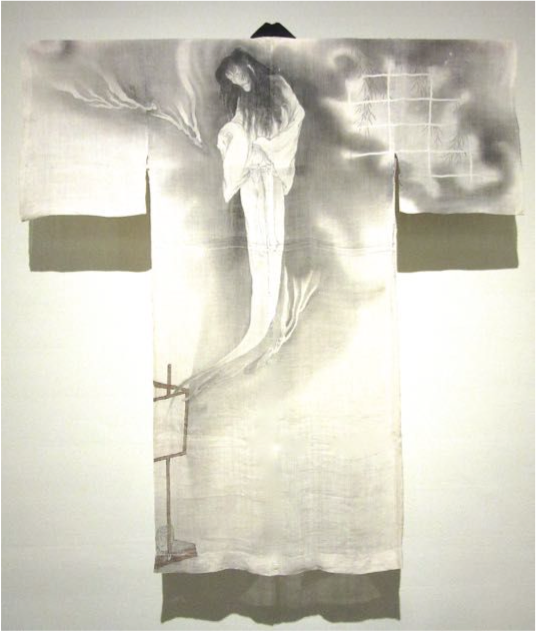

Gothic elements in more traditional Japanese fashion. Hand-painted summer kimono from No Sweat: How Textiles Help Beat the Heat, on view at the Honolulu Museum of Art through September 18.

“…this is going to begin a really nice conversation with the local community about the internationalization of manga as an art form.”

Griff: How do you see manga now, and perhaps in the future, sort of speaking to peoples around the Pacific, and maybe a new industry taking off here or in other Pacific cultures?

Stephen: in talking about the local community of artists here in Hawaii, we do have a thriving manga community that has been active for decades. And in early October, in the Doris Duke Theatre here we’ll have a round table discussion in which we gather together several local manga artists and we want to talk about those issues with them. Later in October, on Friday October 28th Deb Aoki, another Hawaiian manga artist, she’ll be giving a lecture on her work. Again, it’s a great opportunity to learn more about that subject. But to give a simple answer to your question, manga has been alive and well on the Islands here for many decades now. I think that the show is going to be very warmly received for that reason, and I think that this is going to begin a really nice conversation with the local community about the internationalization of manga as an art form.

Be sure to check out Visions of Gothic Angels for more of Stephen’s brilliant insight and stayed tuned to Sartle via Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and our Snapchat (Sartle.com) for other exciting collaborations with the Honolulu Museum of Art in the coming months!

By: Sarah Oesterling and Griff Stecyk