If there was ever a College Board for artists, it would be the art academies of the 17th and 18th centuries, specifically the Academie des Beax-Arts in France. It was founded under Louis XIV, who was just nine at the time, but grew to be a huge patron of the arts as part of his rule over France, making state control over the arts as a tenant of his absolute power. His approach to life is perhaps best summarized through its enshrinement in the Palace of Versailles.

Hyacinthe Rigaud, Louis XIV, 1701.

The first chancellor of the academy, court painter to Louis XIV, Charles Le Brun, ruled with the same fervor as his king, establishing guidelines for artists to follow in order to create good art. His theoretical approach to art set a hierarchy of genres. History was the most prestigious genre, followed by portrait, genre, landscape, animal, and still life. Le Brun also had rules about what was in the paintings and how they were painted calling it the “royal style,” devoted to glorifying the king. The subject matter was to be classical or Biblical and done in the classical style.

Over in England, the Royal Academy of Arts was founded under King George III in efforts to establish Britain as a center of the arts. Its first president, Joshua Reynolds, was also as opinionated as Le Brun, devoting a lecture series delivered at the Academy entitled Discourses on why art should have allegorical conceit.

The Ladies Waldegrave by Joshua Reynolds at the Scottish National Gallery

The academies promoted a distinct style of classical ideals and highly finished surfaces composed of teeny tiny brushstrokes, or “licked surface”, that left no traces of the artist’s touch. This was enforced through their control over the exhibitions through the yearly Paris Salon, which the academy chose the pieces for, and education through the artists’ rite of passage, the Grand Tour, which reinforced the legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance.

Some of the artists exemplary of this style were Poussin and David whose harmonious, geometric compositions of classical subject matter fit all the conventions for the perfect history painting. Their works were popular with the royal and imperial patrons who, through the rationality of their compositions, promoted Enlightenment values like rational thought and loyalty to the state.

Death of Germanicus by Nicolas Poussin at the Minneapolis Institute of Art

Poussin was trained in Italy in the classical tradition, bringing his love of the classical to France. His paintings were utilized by Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu, and his style of clarity, logic, and order was adopted as the royal style. Although the subject matter of his paintings were allegorical, they had anchors to contemporary events, designed to promote loyalty to the state by depicting stories of said state loyalty from antiquity. David had a similar approach, glorifying the government through imagery of the Roman empire at its pinnacle, however his time was marked by political turmoil. He lived during the end of the Ancient Regime, including the overthrow of the monarchy during the revolution and the establishment of the French Republic. He was able to maintain favor during both, applying his aptitude for propaganda to support both governments.

Philosopher Lecturing at the Orrery by Joseph Wright of Derby at the Derby Museum and Art Gallery

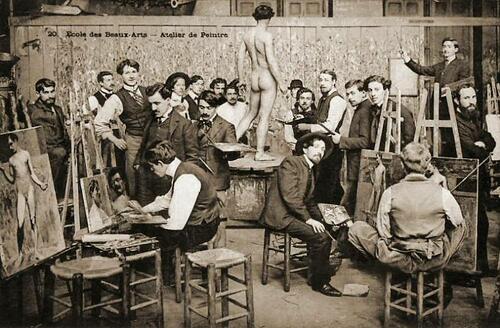

This desire for rationality flowed into the educational institutions which applied the same scientific approach to the creation of art. Art was made into an intellectual pursuit instead of technical, raising the status of the artist. The academy set a standard arts education procedure, and aspiring artists went through vigorous training through study, first learning to draw from ancient sculptures until they were allowed to attend a life drawing class where studied human anatomy by drawing live models. This hazing of future artists instilled in them the principles and doctrines of the academy, ensuring a set standard which all artists conformed. Artists who the Academy favored set the standards for future artists. Watteau and Fragonard, Rococo artists known for their expressive colors and brushwork rather than concentration on line that defined Neoclassicism, were recognized by the Academy even though their style did not embody their teachings. The Academy not only set the standard but also broke it, the style not unchanging but flexible.

The Academicians of the Royal Academy by Johan Joseph Zoffany in the Royal Collection

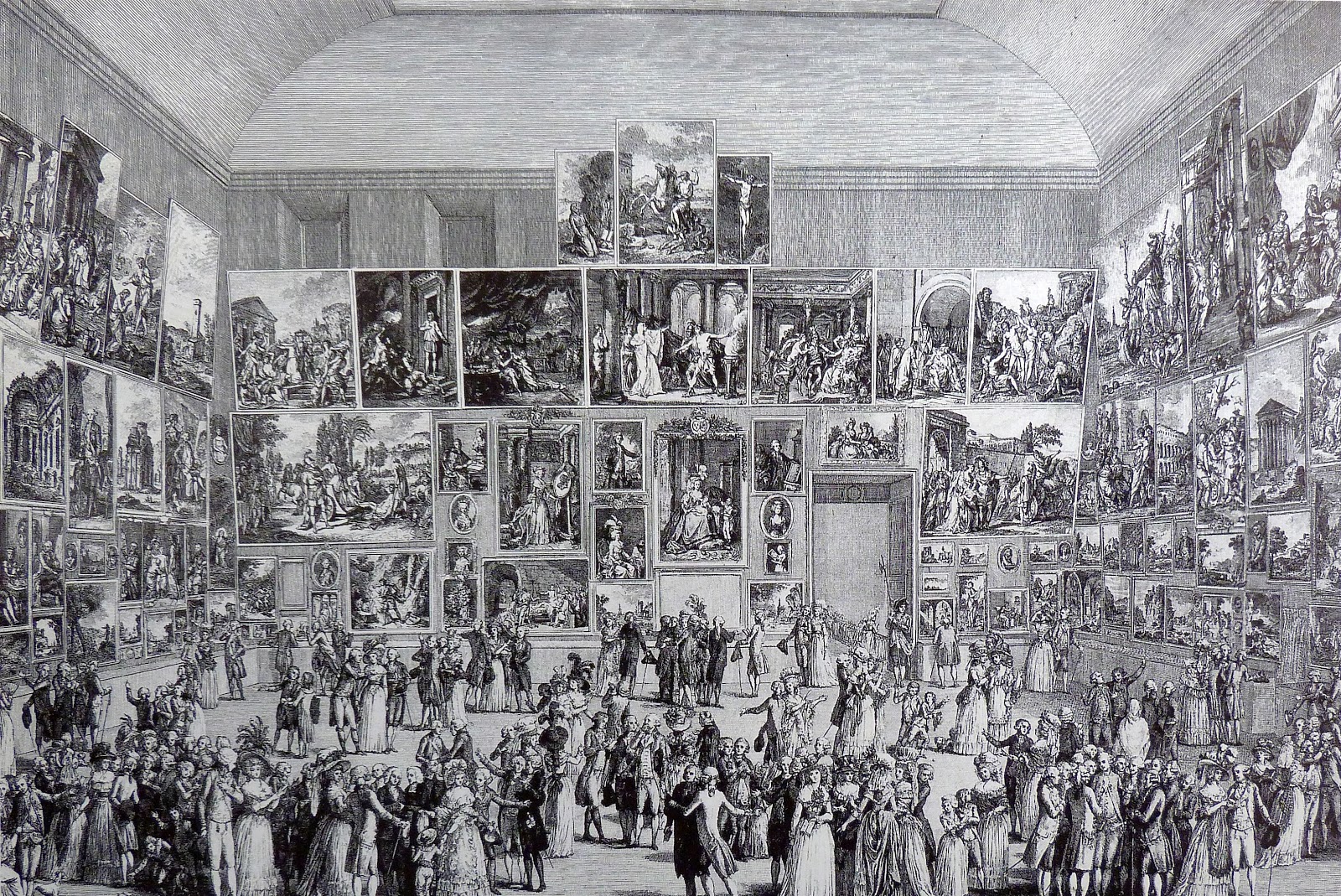

The Academy was in control of the content of art as well, as the major patron as well as the gatekeepers and tastemakers, it commissioned and favored works that conveyed moral messages and loyalty to the state. The largest patron was the state, and regular royal patronage was established in 1774 in France, increasing competition for coveted commissions and yielding yearly exhibitions of art designed to further political agendas. The Academy was wrought with nepotism, and artists like Jean-Baptist Pierre, who were trained and worked in the Academy, gave preference to those who conformed to the Academy’s standards and emulated the style. He chose topics that were designed to imbue certain virtues, glorifying French history and moralizing the French public.

Exposition au Salon de 1787 by Pietro Antoni Martini at the Met Museum

However, as these institutions lost control through periods of political upheaval, most notably the French Revolution, and the art market changed to cater to the tastes of the new middle class, artists who opposed this canon emerged. History painting made way to ambiguously categorized snapshots of everyday modern life as patrons willing to pay the high cost of producing them slowly waned and bourgeois patrons who did not have deep knowledge of art wanted something to hang in their bedroom walls. As art became a more popular industry, catering not only towards the tastes of aristocratic educated elite, the long process required to produce a history painting led to the slow decline of the genre that was emblematic of the Academic style.

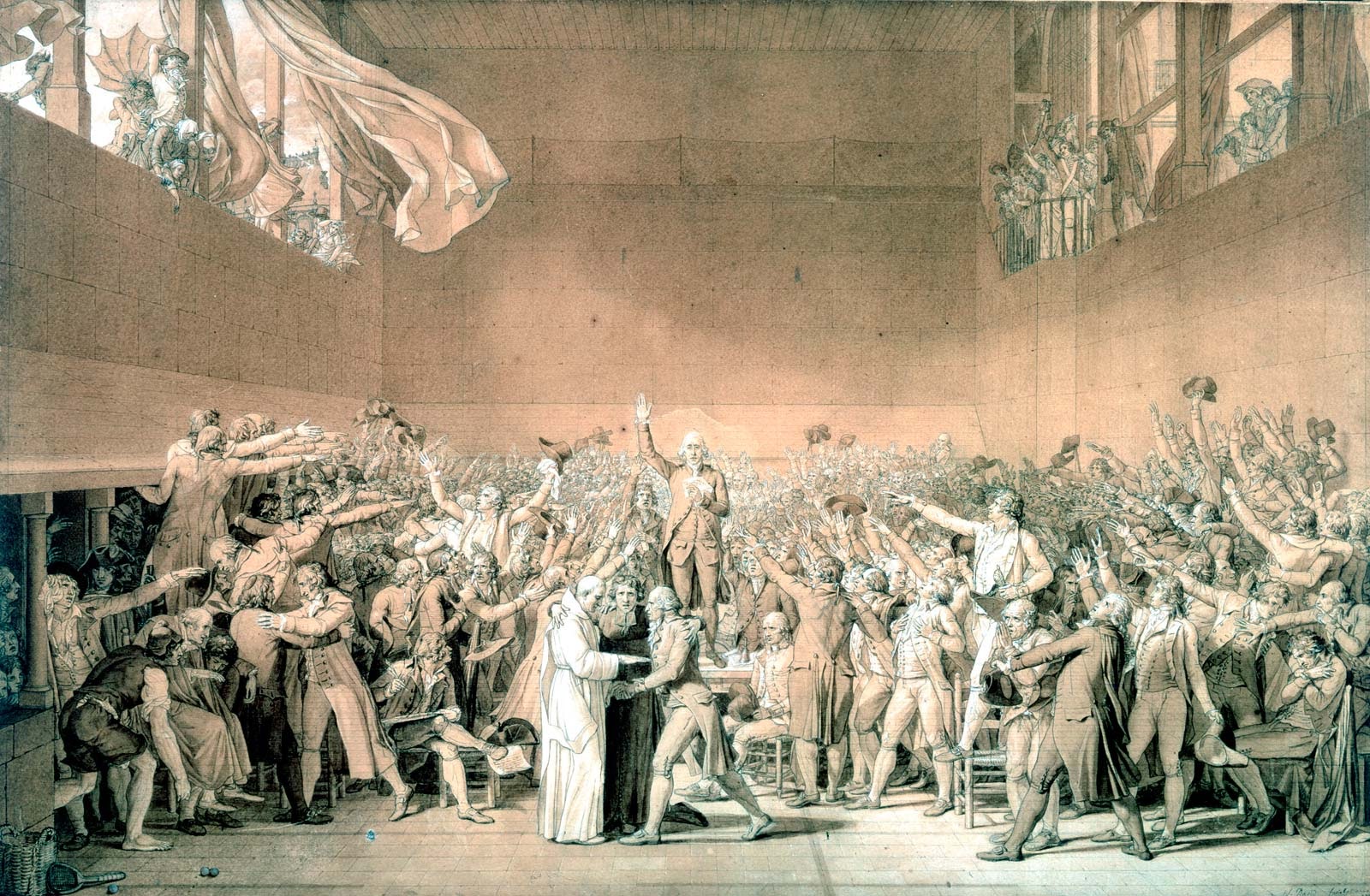

The Tennis Court Oath by Jacques-Louis David at Versailles

Attempts to adapt the format to the changing interests and quickly changing political climate led to pieces like David’s The Tennis Court Oath, which was abandoned because the subject, a scene from the revolution, was irrelevant by the time it was completed and because David struggled to find a patron.

To keep up with the changing tastes, the Salon de Refuses was established to exhibit the paintings that were deemed not good enough for the official Salon. Here the works of avant garde artists like Courbet, Manet, and Pissarro were showcased, ushering a new era of convention-breaking art.

Sources

- Blunt, Anthony (1958). Nicholas Poussin. Phaidon.

- Boime, Albert. "The Cultural Politics of Art and the Academy." The Eighteenth Century 35, no. 3 (1994): 203-22. www.jstor.org/stable/41467772.

- Ettlinger, L.D. "Jacues Louis David and Roman Virtue." Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 115, no. 5126 (1967): 105-23.

- Goldstein, Carl. "Towards a Definition of Academic Art." The Art Bulletin 57, no. 1 (1975): 102-09. doi:10.2307/3049342.

- Jobert, Barthelemy, and Richard Wrigley. "The 'Travaux D'encouragement': An Aspect of Official Arts Policy in France under Louis XVI." Oxford Art Journal 10, no. 1 (1987): 3-14. Accessed February 20, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/1360301.

- McWilliam, Neil. "Limited Revisions: Academic Art History Confronts Academic Art." Oxford Art Journal 12, no. 2 (1989): 71-86. www.jstor.org/stable/1360357.

- Posner, Donald. "Concerning the 'Mechanical' Parts of Painting and the Artistic Culture of Seventeenth-Century France." The Art Bulletin 75, no. 4 (1993): 583-98. doi:10.2307/3045985.

- Uphaus, Robert W. "The Ideology of Reynolds' Discourses on Art." Eighteenth-Century Studies 12, no. 1 (1978): 59-73. doi:10.2307/2738419.

Comments (6)

Thank you for sharing! Very interesting article. I have always been interested in art and everything related to art.

LOL I don't know what Eric is talking about, academic art is literally so boring.

I love academic art, I think it's the most classic looking art form.

Marvelous Post!

History of art is so exciting to explore. Different schools, countries, styles, traditions are unique and beautiful.