This just in: Sartle makes new friends!

Amelia, Victoria, and Susan make up the magnetic trio behind the always fascinating transatlantic website, The Scéal (pronounced shh-kale—we had trouble with that as well). Based in both Scotland and New York, The Scéal tells the hilarious, strange, and often mysterious stories at the intersection of art, fashion, and film. In their own words, they're "as poetic as a Drake meme, as brash as Rizzo in Grease, as conscientious as Leonardo Di Caprio in real life, all with the charm of Liz Lemon." Basically, our kindred spirits.

We hope you enjoy their unique brand of historical banter as much as we do. You can head over to their site at www.thesceal.com to peep some more of the often overlooked facts regarding subjects like Michelle Pfeiffer, Mean Girls, and of course, the timeless fashion of Frida Kahlo. Without further ado—

They Fought The Law and Their Art Won (Part 1)

Charles Manson may have the crown for popular culture’s favorite serial killer but he is mainly spoken of with condemnation, anger or amazement (not the good kind). His ‘Manson family’ had all fallen under the spell of the troubled ex-convict turned cult leader, which led to them committing several murders throughout July-August 1969. Manson was sentenced and imprisoned in 1971, and remained there until his death late last year.

In 2015 his alleged son Matthew Roberts turned the Charles Manson criminal case into a performance art piece at Los Angeles’ Vector Gallery. Roberts played the role of Manson, performing his trial for gallery attendees who took the role of a quasi-jury. It sounds uncomfortable, a steroids induced performance of a Cats in the Cradle father-son relationship, and it swam in murky ethical waters. But as the ‘artist’ Roberts was only acting the criminal in this scenario, posing new interpretations of Manson’s innocence and walking away relatively unscathed (mentally though, I doubt it). What would we now think of seeing Charles Manson’s artworks on the gallery walls? What if Manson was the one producing performance art in the contemporary art gallery? What if he was an untapped well of artistic talent, the greatest painter of our time?

It’s doubtful that we’d treat him with the same respect, appreciation and enjoyment we have when, say, seeing a painting by Caravaggio. Yet, Caravaggio was far from an innocent lamb with eight crimes under his belt before his early death at barely 40 years old. So why do we forgive his criminal biography, praise his genius and romanticize his mysterious past? How also would you treat an artist who you knew was a thief, stealing invaluable national treasures? Enter, Picasso. Here we delve into the darker side of art in part one of our series They Fought The Law and Their Art Won.

Caravaggio: Artichokes and Murder

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) epitomized the fame and power bestowed upon talented artists in Baroque Italy. As he gained the patronage of the powerful figures of Rome, he became one of the most sought out artists of his time. His paintings are renowned for his ability to render emotional depth, light and naturalism. But his place in art history is amplified by his personal life, earning himself the titles “...notorious bad boy…”, “the master of darkness” and that’s all just from one art historian, Gilles Lambert’s Caravaggio, my new favorite book. The gaps in his biography, especially in his early training and youth, are balanced with the sensational details of his sudden rise to fame and wealth when he started working in Rome. From dabbling in smaller criminal charges, to murder, we see Caravaggio steadily declining into a life of criminality - one that even his Vatican patrons couldn't pull him out of.

In 1595, Cardinal Francesco del Monte saw The Big C’s potential and adopted him into his household, helping him to gain several public commissions. Prior to this Caravaggio had been selling his paintings on the streets of Rome trying to make a living from his talent. Thrown into his new circumstances he was given plenty of opportunities to paint and experience the virtues and vices of Baroque Rome. It also meant that he had exclusive access to some of the most powerful men in Rome, with his works being greedily snatched into the private art collections of cardinals and patrons.

The Cardsharps by Caravaggio in Kimbell Art Museum

He was stuck flip-flopping between approval and disapproval; in one instance painting the prominent, religious commission for the Vatican at St. Peter’s (below), which was then removed by the church and offered up for sale (bought later by Cardinal Scipione Borghese).

Madonna and Child with St. Anne (Dei Palafrenieri) by Caravaggio in the Borghese Gallery

From 1600 to 1606 he had commissions out the whazoo, but also seriously flirted with crime and the law courts. He was saved from sentencing in these early instances by his patrons, the Marchese Giustiniani and also a handful of cardinals. This seemingly never-ending and public battle that he had with the law meant that the Vatican knew full well of his criminal doings. His relationship with the church would have been further exacerbated when he assaulted a Vatican official in 1605. Surely someone in the Vatican had heard the saying “fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice, shame on me”?

Some of Caravaggio's crimes included possessing a weapon without a license, street fighting and throwing artichokes at a waiter. The latter is potentially understandable if they were undercooked, or under-seasoned and he’s hardly the only artist who appreciated their food. But from 1598 the crimes he committed grew in severity and frequency, from escaping prison after murdering a sergeant to a second murder charge. This lead to him fleeing to Malta and Sicily in 1606. His moral compass was askew but rather than send his career into tatters he continued to work successfully. His paintings even benefited from his changing attitude to life and mortality. After it was announced on 31 May 1606 that Caravaggio was sentenced to death, the cities and countries that he fled to readily took him in and he continued to produce some of his most expressive works, such as David With the Head of Goliath from around 1610.

David With the Head of Goliath by Caravaggio in the Borghese Gallery

Even now Caravaggio’s paintings have been recognized for his talent and his biography always swirling with intrigue and mystery. With two films based on his life and numerous novels and historical texts, we are still fascinated by this man who could barely balance his brilliant abilities in art with a frenzied life of power, privilege and criminality. If he was alive today he’d be on the headlines of the Daily Mail every weekend, but would we still love him as much as we do now and would we still worship his paintings?

Picasso: Thief (?)

Picture now, Pablo Picasso: Cubist hero, poster boy of pushing the boundaries of modern art, peace campaigner, collector of muses, all round great guy - right? What if he was, instead, just a lousy little thief? At one stage, that’s exactly what the French judicial system thought of him. Let’s take a look at Pilferer Pablo’s rap sheet.

What follows is a crime story that sounds more like BBC prime time viewing than an actual case of art theft. On the morning of 21 August 1911, Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was stolen from The Louvre. Don’t know enough about Mona Lisa? Let Will.I.Am enlighten you. In a hilarious case of staff miscommunication the guards had assumed that the painting had been removed by another staff member. This is why Slack was invented. When they discovered the frame in the service stairway they suddenly realized their error - so the crime wasn't reported until the following day. The police were at a loss as they had little leads and little clues. It wasn't until the newspaper The Paris Journal received an anonymous tip-off from the con-man Honoré Joseph Géry Pieret who the paper labeled ‘The Thief’ in their articles, that the case gained momentum. Pieret and the journal whipped up a media frenzy, as visitors were queuing to simply see the gap left where Mona Lisa used to be, and he eventually implicated the poet Guillame Apollinaire in the crime. The police arrested Apollinaire in September and during his questioning he admitted that Pieret was indeed a thief and had sold statues stolen from the Louvre to none other than (*drum roll*) Pablo Picasso.

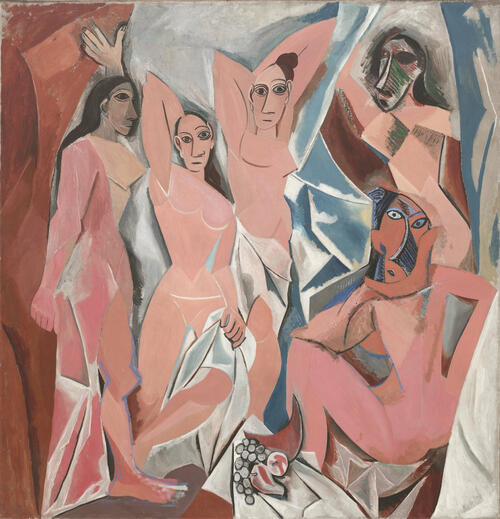

The police files of the time show how Picasso had already been on the radar of French officials as far back as 1901. This was originally due to his association with Pere Mañach, Spanish art dealer by day and an anarchist by night. The French police had kept Picasso and Mañach under surveillance for several years, as discussed in the New York Times’ ‘Picasso in Paris…’ (my recommended read of the day FYI). Anarchist or no, the evidence for his only crime was all located in Picasso’s flat; he most certainly had two pre-Roman statuette heads stolen from the Louvre in 1907. So although he was innocent in the case of the missing Smiley Mona he was nevertheless a criminal. However, his art did not suffer - in fact it had benefited from his possession of stolen museum goods. The statuette heads served as the inspiration for his Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso in the Museum of Modern Art

Abandoning the historical approach to the human form, Picasso’s Les Demoiselles depicts five nude women composed of bold lines, flattened shapes and dismantles all assumptions about how to portray the female figure. It is now considered one of the most influential works of modern art. I’ve always loved Picasso for his versatility, some of his earlier works are brilliant studies of draftsmanship and his talent in studying the academic tradition. To find out that some of his most revolutionary works existed because of a crime surely lessens their impact, right? The MOMA, New York has this painting in their collection, yet in their gallery label no mention is made of how Picasso’s inspirations were a product of a crime. Surely we should talk about this more?

Picasso’s crimes, although only by association, did not dissuade the art world from collecting and embracing his works. Similar to Caravaggio, his genius has trumped his run-ins with the law. In both cases their artworks benefited from their criminal activity - be it through continued patronage, or new sources of inspiration. They weren't the last artists to dabble on the dark side, though, as we find out in our next post: Dissidence and Charges Against Morality. Coming soon.

By Amelia Rowland

Reposted with permission from The Scéal by Rose

Comments (7)

I agree!

New goal: Make enough of a fuss to get sued!

So far nothing has made a fuss.

These are all so cool!

The picasso story is my favorite

Agreed!

These are so great please do more!