Disclaimer: This article contains amazon affiliate links.

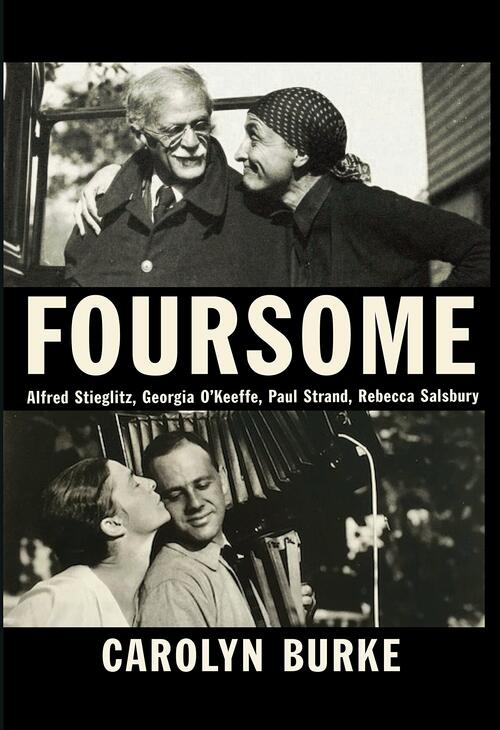

Can any biographer truly account for their subject’s life without also accounting for the lives of those intertwined with that subject? Those books which promise a comprehensive overview of any one person without also thoroughly examining those close to that person often end up being more theatrical than they are truthful. What makes Carolyn Burke’s latest book, Foursome (find it on amazon here), such a refreshing step away from that traditional mode of biography is in its wider scope and intention to document FOUR lives—Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Rebecca Salsbury—instead of just one, and on top of that, the objective to document the dynamic shared between the four artists at the height of their friendship during the early-to-mid-twentieth century. The book is a snippet of life, a snippet of history, a snippet of artistic genesis, while being at the same time a full show of each artist’s relationship to the others. Take heed, art history fandom: the stories Foursome tells of this famous group of friends and lovers are often poignant, sometimes sad, and almost always scandalous.

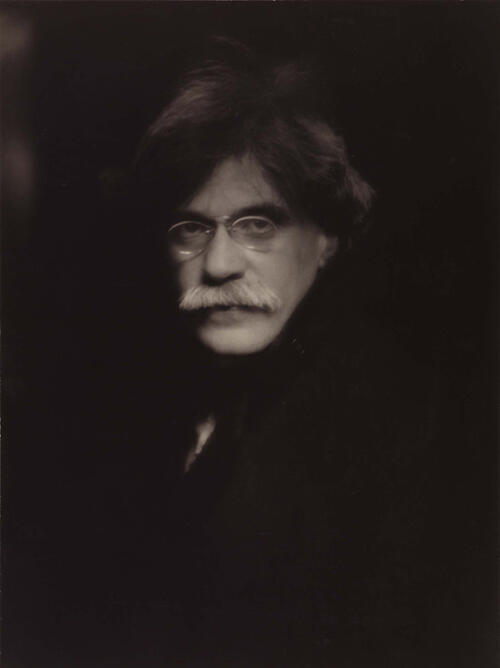

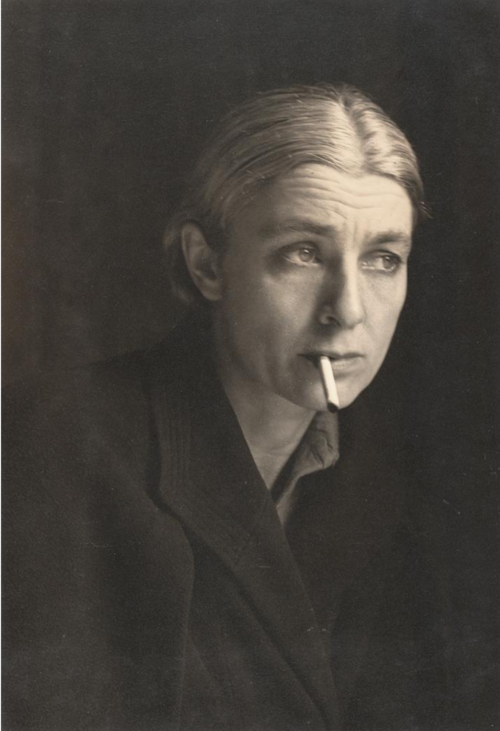

Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz is arguably the main player of this book, partly due to his being older than everyone else (so he gets to play dad while also sometimes being super competitive with Strand and pretty creepy and sleazy towards Salsbury and O’Keeffe, the latter of whom would eventually marry him anyway). The book dives a little bit into his background as the son of German Jewish immigrants, and outlines his desire to define himself as American against the backdrop of xenophobia and anti-German propaganda coming out of World War I. Eventually, Stieglitz would turn his passions toward the camera, and much of the early portion of Foursome is devoted to his starting and stopping of various clubs and art galleries, as he was imbued with the belief that photography (still a relatively new invention) should be taken seriously as its own legitimate art form.

Music: A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs, No. 1, 1922

Burke succeeds in painting a vivid picture (er, taking a quality portrait?) of Stieglitz as an essential catalyst for photography’s transition in the general public’s mind from that cool thing that takes forever to pose for to a high-class, “serious” medium for art. If you can get past the lofty pseudo-spiritualism and abundant use of sexual innuendo that proliferate his essays and letter correspondence, you will find a very impassioned advocate for the arts and a vital figure from history who believed in the value of innovation and the avant-garde as much needed nourishment for America’s soul.

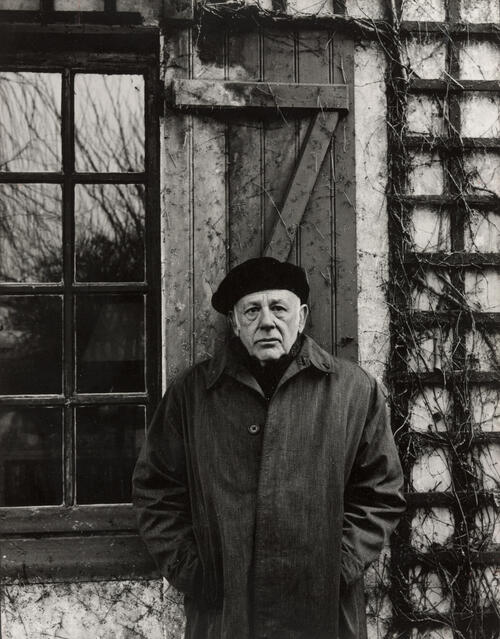

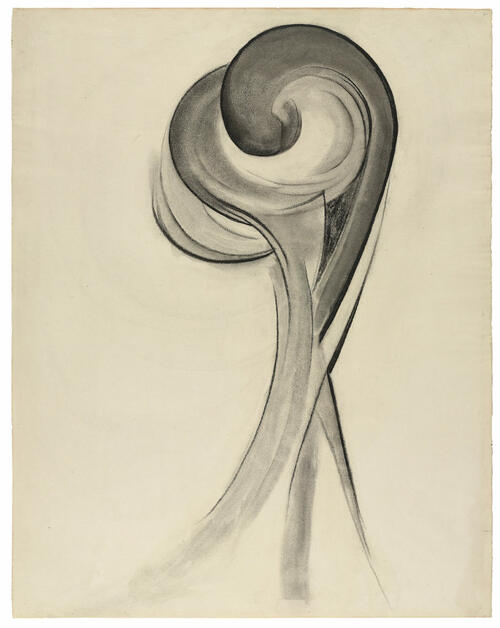

Paul Strand

If you’re not so fond of Alfred Stieglitz, you’ll probably like Paul Strand even less, who dedicated a good portion of his adult life to telling people how much he really liked Alfred Stieglitz. Meeting his would-be mentor by showing his own photography at the up-and-coming art gallery 291, the young Strand was smitten with Stieglitz’s positive response to his work. In their meeting lays a predominant theme which runs throughout much of Foursome—that of Alfred Stieglitz using his power and influence to get other people famous. Still, I quite like much of Strand’s photography; his obsession with shapes and angles make for some really compelling compositions, and his study of the burgeoning cubists (like Pablo Picasso) really shows in much of his work.

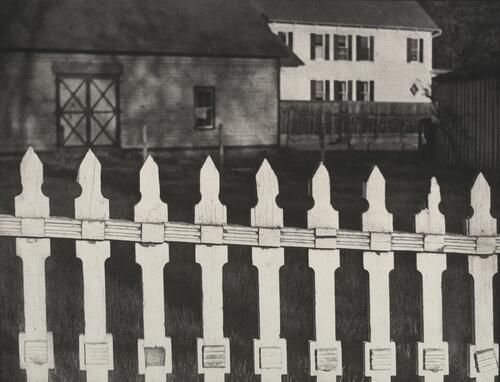

The White Fence, 1916

Strand comes across in Foursome as technically brilliant, though emotionally distant. In a book about the relationships between people, Strand ultimately becomes the least engrossing of the bunch. Much of his letter correspondence is lost, but what we can infer from those who were in contact with him portrays a character who loves and shows a deep fondness for humanity in the abstract; personal relationships, on the other hand, get less of that treatment. This aloofness rocks more than a few boats in the story of Foursome, and ultimately leads to Strand’s divorce with Rebecca Salsbury. He certainly did a lot in the way of advocating for photography as an artistic medium to be taken seriously by critics, but one wonders what kind of person Strand was on the day-to-day, when he wasn’t “record[ing] truthfulness.” The book’s not supplying us with that answer is no failing on the part of Burke as writer and researcher; indeed, Strand’s enigmatic behavior plays a key role in the natural tension of this group’s dynamic, his elusiveness intriguing for readers as much as it can be, at times, frustrating.

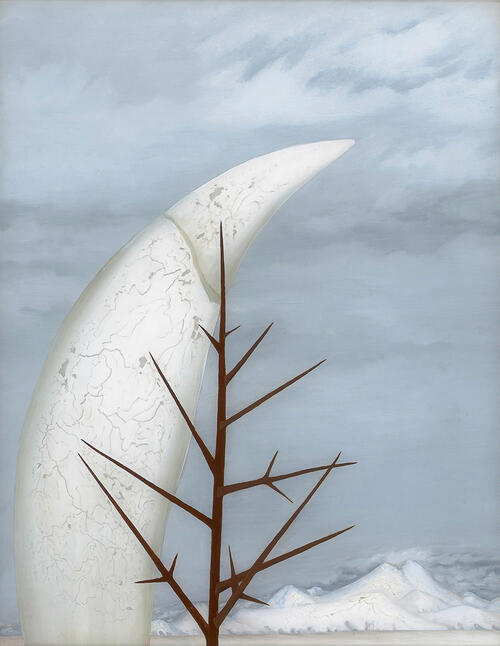

Rebecca Salsbury

In many ways, Rebecca Salsbury is the glue that holds all four artists together for a period of time much longer than would have likely been otherwise. She comes into the book the latest, first getting acquainted with Strand before eventually getting involved with Stieglitz’s whole modernist posse. Though she would come to be a talented painter in later years, much of Foursome involves her grappling with insecurity over her own artistic worth. While Strand and Stieglitz would have been perfectly happy keeping Salsbury around only as their model (Strand: “Sit still!” Stieglitz: “Be more naked!”), Rebecca, or “Beck,” admits to very real creative desires of her own in her excerpted letters, desires which would ultimately determine her career as an artist. Nevertheless, it would appear that being around all of these modernist eggheads ultimately both nurtured and hindered those impulses.

Winter in Taos, 1948

In the book’s detailing of her letters, Beck comes across as the most genuine and open of the group. There is a section during which she travels to New Mexico with Georgia O’Keeffe, and their bonding experience is lovely, and even uplifting. Beck comes from a rootin’-tootin’ background (her father worked with Buffalo Bill in their famous Wild West show), and those roots stick with her throughout the story; you will often find Beck smokin’ cigarettes, wearing pants (!), and even mingling with the everyday folk—all of this while simultaneously coming from a wealthy family, serving as her mother’s fancy travel companion, and paying to support her husband’s photography endeavors whenever his job prospects weren’t so hot.

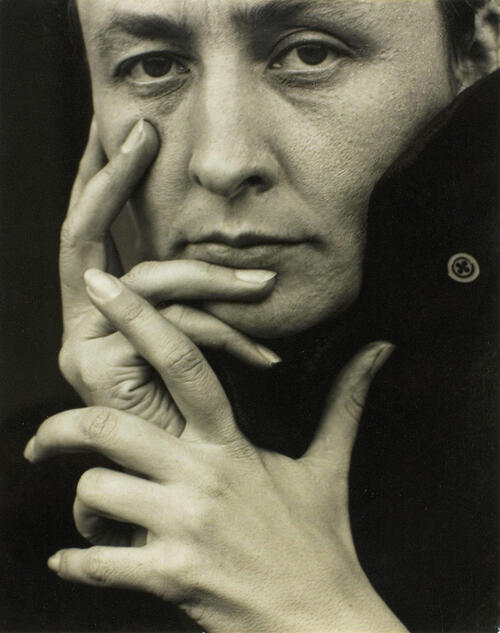

Georgia O'Keeffe

Perhaps most revelatory in Foursome is the exposition of a young, hot-headed Georgia O’Keeffe as revealed in her letters, which were written well before the artist would rebrand herself as more reserved and “cool” and really into painting cow skulls. These letters, particularly the ones to Stieglitz, showcase a young artist filled with palpable emotion and great enthusiasm for nature; her frustrations with her job as a teacher and her various romantic entanglements with many, many lovestruck suitors help to establish in her character a rebellious quality and allure that critics would eventually trace all over her work. She is volatile and yet extremely self-possessed, and her writing displays a deeply romantic thinker obsessed with nature and landscape and the feelings they inflict upon the body and mind. Those shippers of Stieglitz and O’Keeffe will delight in their steamy letter correspondence getting relayed here in Foursome. At times it can get pretty intense—I’m talking phallic-railroad-train-imagery intense.

No. 12 Special, 1916

Alas, it would be a mistake to only talk about sex when talking about Georgia O’Keeffe, as so much of her artistic career involved her battling against these predominant, Freudian readings of her work, in which everything is a vagina and O’Keeffe herself is a living, breathing symbol of liberated femininity, a source of hope for ladies and a tantalizing puzzle for stupid men. Much of the narrative deals with O’Keeffe’s efforts to exist outside of those hackneyed critical confines, as well as the other three artists’ efforts to assist, and sometimes sabotage, her (Strand writes some impassioned, defensive essays; Stieglitz displays nude portraits of her and sets up a sensationalist media circus; Beck takes her hiking).

As a whole, Foursome is a unique look into the social personalities of these four artists, and by interweaving relevant historical context we are allowed insight not just into how they interacted with each other on a daily basis, but how their larger, modernist social circles lived too; it is a confusing, Freud-obsessed, avant-garde beauty pageant at times, this world of the early twentieth century artistic and intellectual elite, and should come off as both a familiar and strange place for contemporary audiences, ultimately making for a fascinating read! Heartbreaks, sexy correspondences, and modernist sass are just some of the many treats Carolyn Burke faithfully uncovers in this biography. Be sure to pick up a copy and check it out for yourself.

Carolyn Burke, Foursome: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, Paul Strand, Rebecca Salsbury (New York: Knopf, 2019).

Other books that may be of interest:

-

Georgia O'Keeffe and Her Houses: Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu - Barbara Buhler Lynes & Agapita Lopez (amazon)

-

My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz - Sara Greenough, editor (amazon)

-

Paul Strand in Mexico - James Krippner & Alfonso Morales Carrillo (amazon)

-

Alfred Stieglitz: Taking Pictures, Making Painters - Phyllis Rose (amazon)