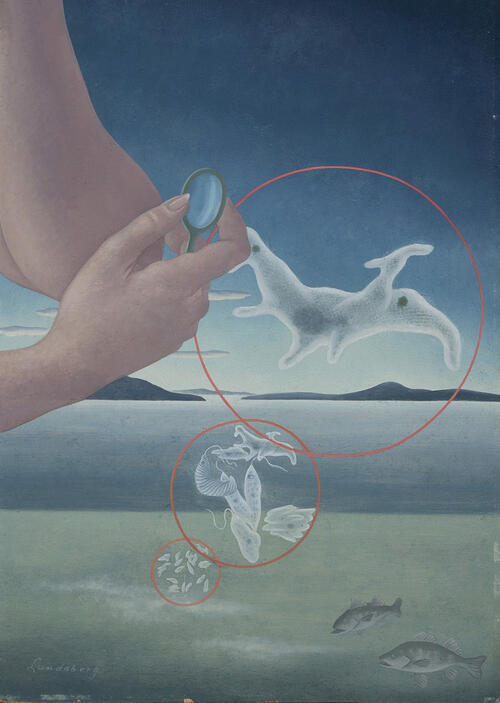

Helen Lundeberg’s Self Portrait, 1944

Imagine all of Einstein’s writings, jottings, and mathematical theorems in crayon and you’ll get an idea of Dimensionism, a largely forgotten art movement from the first-half of the twentieth century. That’s not to say that the artwork made under this tag shouldn’t be taken seriously or that it is childish. Quite the opposite. The current exhibit at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, called Dimensionism: Art in the Age of Einstein, with its dazzling and confounding collection of Dimensionist paintings, photographs, and sculptures, proves that the movement deserves to be much better known. It is the premiere of a nationally touring exhibition organized by the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College.

The Dimensionists were a group of avant garde artists working in the 1930s. “Its unconscious origins reaching back to cubism and futurism, it has been continuously elaborated and developed since then by all the peoples of Western civilization.” That’s Charles Tamkó Sirató, the author of the Dimensionist Manifesto, which is presented in full in its original Hungarian and a later English translation at the exhibit. It’s definitely worth a read, and was able to attract quite a few big names to sign it: Marcel Duchamp, Wassily Kandinsky, and Joan Miró are just a few.

Gordon Onslow Ford’s The Dialogue of Circle Makers, 1944

When you first walk in, passing by the hypnotic exhibit sign with a color palette reminiscent of the infamous black and blue dress that once made friends question their mutual trust, you will likely feel overwhelmed. It’s a large open room with walls covered from end to end with three-dimensional paintings, multi-level collages, and dangling mobiles. Around the room on pristine tables are strange sculptures that elude a simple take. If one walks into the exhibit without foreknowledge of what it is about, you might become slightly frustrated and want to leave early, much like the couple I overheard mumbling about the confusing artworks, with their hands to their back and bodies arched towards the exit.

Take your time. The exhibit is worth a deeper look.

One of the first artworks you’ll see is César Domela’s “Abstract Construction”. With the visualization above, you should get the idea of how dimensionality plays into their work. It’s a canvas that appears two-dimensional from front, but is in fact three. There’s a nuance here, however, that is not clear in the photograph. The dots are lit up by light bulbs within the metal frame. With the presence of light, it places the artwork into the fourth dimension, that of time. This is huge for the dimensionists.

Let’s get back to Einstein, the focus of the exhibit. The Dimensionists were by and large grappling with his then-radical theory of relativity. They recognized it as a monumental shift in consciousness, where space and time did no longer equal two, but instead as one cosmic mechanic. In fact, this is a central tenet of their manifesto, with Sirató writing that Dimensionists must accept the unity of space and time.

Marcel Duchamp’s Rotorelief No. 5 – Poisson Japonais

Dimensionism takes care to provide numerous examples of the fourth dimension in art. Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs stand out as the most accessible, something you might even see in a college dorm room. The most remarkable, perhaps, are the photographs, like Harold Edgarton’s famous “Milk Drop Coronet” which is a joy to see in person.

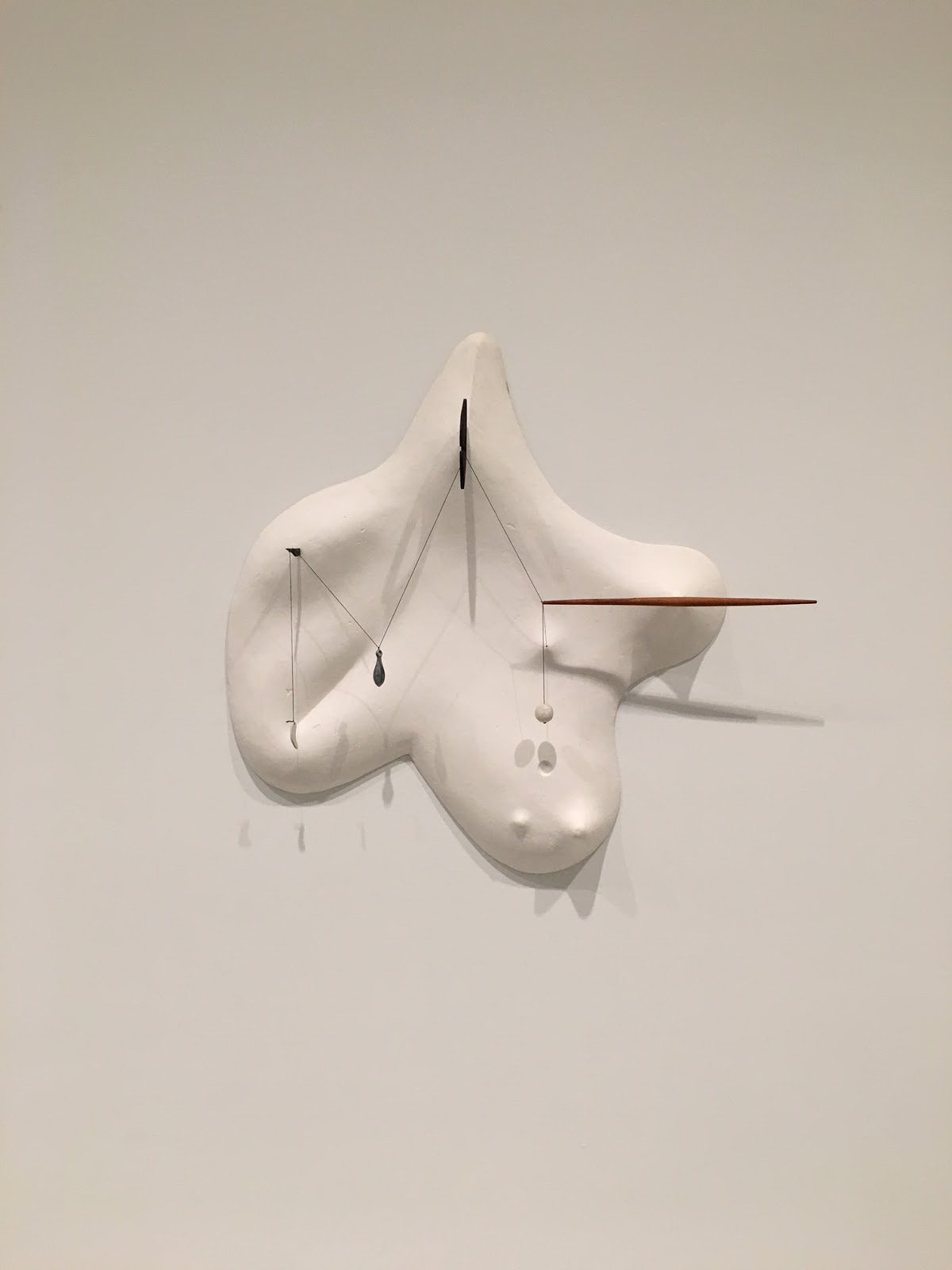

Isamu Noguchi's Yellow Landscape

The headiest pieces on show are definitely the sculptures, where thoughts on space, time, and quantum mechanics are explored in voids and unusual angles. Specifically seeking non-Euclidean geometry, or that outside of what we learn in grammar school, the artists sought to break away from single point perspectives and mathematically even presentations. Isamu Noguchi, the famed artist and landscape architect, whose work displays a real fondness for Einstein’s theories, has perhaps the most striking sculptures here. They are strange, colorful, humorous, and oddly beautiful.

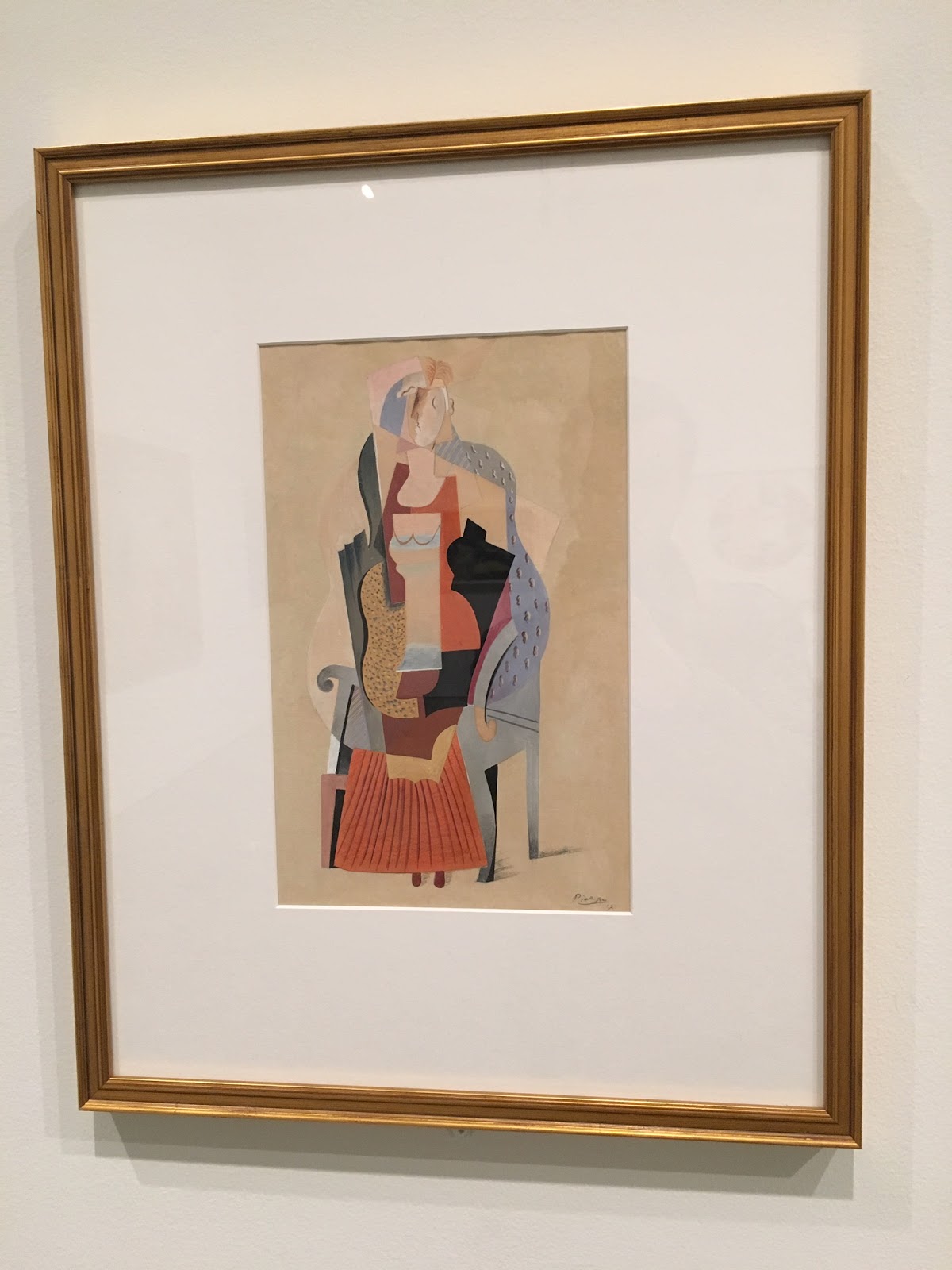

Walking into the second big open room, the displayed artwork becomes a bit more focused in theme. Here, we have two sharply defined areas: first, artwork inspired by quantum theory and, secondly, art made with biomorphic forms, or those unbelievable shapes of amoebas, fillae and other tiny creatures. In the first, the histories of surrealism and cubism are apparent. Picasso himself peeks his head into the conversation with a painting that is surprisingly delicate. Another, about the destructive power of the atomic bomb, will stop you in your tracks. The biomorphic showings are also noteworthy, particularly Kandinsky’s interpretations of stars and comets.

Picasso’s Young Girl in Armchair, 1917

Perhaps the standout of the exhibit is the artwork from Helen Lundeberg. Unfortunately, there are only two paintings here. They stay with you, however, especially because each serves as a soft conclusion on the themes held by the two respective rooms. They are less experimental, and more mystical, investigating how spacetime affects perception and how the discovery of microorganisms might affect our understanding of landscapes. They look like they don’t quite fit in with Sirató’s Dimensionism, but they also open up the exhibit to deeper and broader questions. How can art and science be meaningfully brought together? Lundeberg provides the most compelling and beautiful bridge between the two worlds, worlds that in the current climate can appear diametrically opposed to one another.

Detail from Helen Lundeberg’s Microcosm and Macrocosm, 1937

Through Lundeberg’s paintings, it becomes clear that the Dimensionists were avant garde thinkers who were fascinated by the prospects of science in general. They wanted to grapple with the radical theories of quantum mechanics and the squiggly, oozy shapes and forms of microscopic life because they gave a look into a vibrant future. It was the look into a brave new world. It was a call and response between art and science.

If you are interested in science, if you are interested in art, particularly in art that is not afraid to explore mediums, check out Dimensionism: Art in the Age of Einstein. It’s a necessary exhibit that reminds us that art and science can benefit from the other. It’s an exhibit you’ll remember for quite a while.

Dimensionism: Art in the Age of Einstein runs until March 3, 2019 at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, California.

Sources

- Malloy, Vanja, and Károly Tamkó Sirató. Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein. Amherst, MA: Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, 2018.