This year marks the sixth Academy Award nomination for Leonardo DiCaprio. DiCaprio has survived numerous career pitfalls including the type casting of teen idol-dom, the quotably bad dialogue of Titanic, sharing the screen with cinema’s two biggest scene stealers (a.k.a. Kate Winslet)

…and five epic Oscar losses. But he’s finally done it! Here’s how:

In The Revenant, DiCaprio survives (SPOILER ALERT) a bear attack, freezing temperatures, multiple arrows and his most unflattering beard yet to hopefully win that coveted gold statue. Along the way, he also takes an awe-inspiring odyssey through Art History.

Looking Down Yosemite Valley, California, 1865 by Albert Bierstadt, in the Birmingham Museum of Art.

As striking as DiCaprio’s performance is, the real star of The Revenant is its breathtaking vistas. Few artists captured the Romantic idyll of the West quite like Albert Bierstadt. The film explores the dark side of Manifest Destiny, the grandeur of the landscape clashing incongruously with the human depravity. Director Alejandro G. Inarritu presents a nightmarish vision of the American West, far removed from Bierstadt’s sweeping wilderness bathed in golden light.

Location shot from The Revenant (2015).

Inarritu’s depiction of the pioneer spirit gone wrong is more akin to another Bierstadt landscape, which depicts a glowing mountain pass which also happens to be the site of America’s most notorious case of cannibalism. In the winter of 1846-1847, the Donner Party, a group of Christian families, was snowbound in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and survivors, including women and children resorted to feeding on the flesh of the dead.

View of Donner Lake, California by Albert Bierstadt, in the de Young Museum.

True to form, Bierstadt’s interpretation is more the West according to Thomas Kinkaid than a place where the last vestige of human decency goes to die. The Revenant’s blending of the beautiful and the depraved would fit right in with a big-screen blockbuster about the Donner Party.

Location shot from The Revenant.

In his British Romantic sort of way, J. M. W. Turner had the same idea with his obsession with the sublime. The sublime is basically that place in nature where horror meets exaltation, which describes the film’s depiction of the American landscape perfectly.

Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps by J. M. W. Turner, in the Tate Britain.

Frontiersmen crossing snowcapped peaks: scene from The Revenant.

Of course, no stark reimagining of the American ideal would be complete without some mention of the people who had been here for thousands of years before Europeans and white Americans decided to “discover” the West. In prevailing cinema, Native Americans have been either bloodthirsty villains in need of subjugation, whiskey-swilling buffoons, or something more benignly sinister as seen below:

Mounted Indians Carrying Spears by Rosa Bonheur, in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

French artist Rosa Bonheur was a close personal friend of Buffalo Bill’s, and a fan of his Wild West Show. She had never set foot in America, and while she attempted to depict Native Americans with comparative dignity and realism for the era, they nonetheless appear here as props in the white man’s romance of the “Noble Savage.” The Revenant seeks to provide an antidote to this simultaneously fawning and dehumanising myth by offering up a more complex brand of Native American hero; a fierce but just defender coping with the trauma of invasion.

In the film, a Native American chief searches for a daughter captured by the white men: scene from The Revenant.

Leonardo DiCaprio observes a pyramid of skulls: scene from The Revenant.

Director Inarritu and production designer Jack Fisk conceived of this image as a pyramid of human skulls, alluding to the genocide of Native Americans. After viewing a historic photograph of buffalo skulls stacked in a pyramid, they decided to recreate the real-life photo to represent the mass extinction of the buffalo, resulting from over-hunting by white settlers. Vareshchagin’s The Apotheosis of War offers a haunting glimpse of what the scene might have looked like with the original human skulls.

The Apotheosis of War by Vasily Vereshchagin, in the State Tretyakov Gallery.

In another of the film’s surreal dreamscapes, DiCaprio hallucinates the ruins of a church in the wilderness. Fisk drew inspiration from Russian Orthodox religious iconography, but gives the church a primitive New World feel with a disturbing edge. The frescoes on either side of the crucifixion are based on historic etchings of Spanish Catholics torturing indigenous peoples.

Production still from The Revenant.

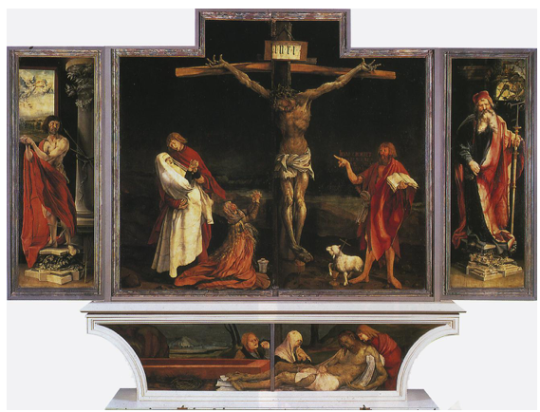

The figure of the Christ is cohesive with traditional church imagery, such as the Isenheim altarpiece, seen below. The frescoes of torture are also surprisingly in line with the historical record of church art. Scenes of violent retribution and hellfire were very popular methods among colonial missionaries for coercing indigenous people into conversion.

The Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald, in the Unterlinden Museum.

The redemptive power of faith is given deeply sinister overtones with the depictions of indigenous Americans slaughtered by agents of the Church. That blend of the reverential and the grotesque is a page out of the Hieronymus Bosch school of religious iconography.

The Last Judgment by Hieronymus Bosch, in the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.

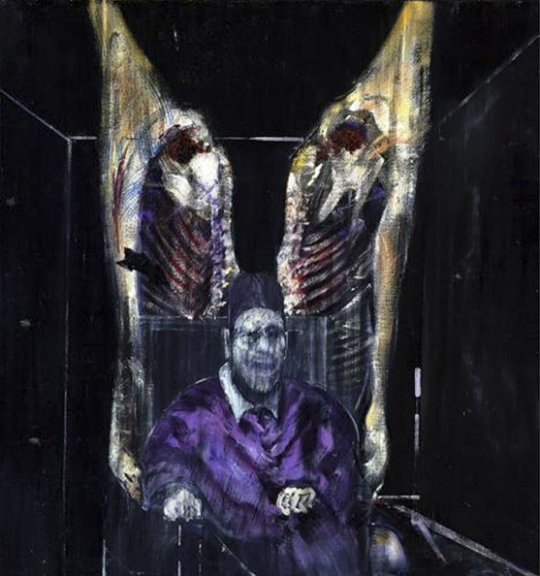

I won’t explain how Francis Bacon’s Figure With Meat fits into DiCaprio’s epic journey through Art History, so as not to include too many spoilers. If you’ve seen the movie, you get it. If you haven’t, let’s just say it may be the least attractive nude scene ever captured on film.

Figure with Meat by Francis Bacon, in the Art Institute of Chicago.

There, now, aren’t you intrigued. Now you have to see the movie.

Congratulations Leo, you deserved it.

By: Griff Stecyk