In her seminal 1985 novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood paints a nightmarish picture of a post-democracy America. Christian fundamentalists and misogynist despots have scapegoated radical Islamic terror as a pretext for suspending all civil liberties. Environmental irresponsibility has led to toxic food and water and a drop in fertility rates. Female bodies are commodities controlled by the state, gay people and abortion doctors are prosecuted according to Biblical law, and people of color are deported to uninhabitable “colonies.” In short, it is pure fantasy with no relation whatsoever to our current political climate.

Surely it must be The Handmaid’s Tale’s quaint escapism that has made Hulu’s recent adaptation of the novel into the most hotly anticipated series of the season. It might make a light diversion if, in the words of our supreme leader, you’re “sick and tired of all the winning” we’re doing. To aid your diversion, I’ve compiled some examples from art history that prove the hostile patriarchy presented in The Handmaid’s Tale is just a feminist myth, with absolutely no grounding in Western culture.

Handmaids of the Good Book: you won’t see this on VeggieTales!

Dante’s Vision of Rachel and Leah by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in the Tate Britain.

Margaret Atwood prefaces her novel with a passage from the Bible:

“And when Rachel saw that she bare Jacob no children, Rachel envied her sister; and said unto Jacob…Behold my maid Bilhah, go in unto her; and she shall bear upon my knees, that I may also have children by her.” – Genesis 30:1-3.

In ye olde Holy Land, Rachel and her sister Leah were sister wives who were also literally sisters. Both married Jacob, patriarch of the 12 Tribes of Israel. The fertile Leah bore him six sons, whereas Rachel had difficulty conceiving. Luckily, biblical patriarchy had a cure for that; namely offering your enslaved women as vessels of childbirth for your husband to inseminate. Rachel’s handmaid Bilhah bore Jacob two sons, who Rachel claimed as her own. Just when everything was going so well, Leah and Jacob’s son Reuben decided he wanted in on the action.

“And it came to pass, while Israel dwelt in that land, that Reuben went and lay with Bilhah his father’s concubine.” – Genesis 35:22

Reuben brought dishonor to the family by plowing with his father’s heifer, but Bilhah, the passed-around handmaid with the “for rent” sign on her womb got the real raw end of this sick family deal.

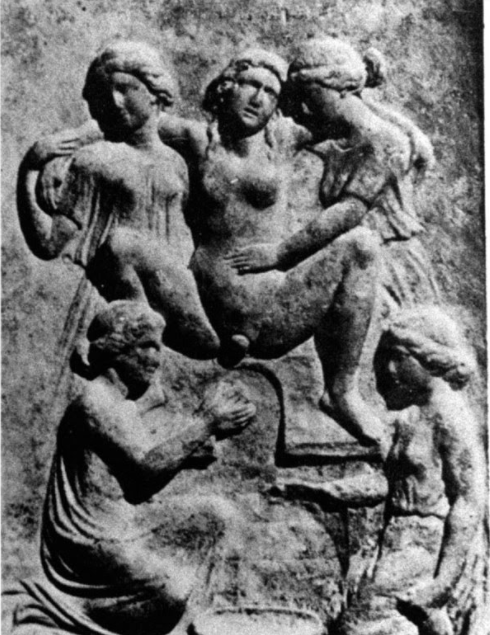

This ancient stone carving of a woman squatting in childbirth in the arms of midwives invokes Bilhah bearing “upon [Rachel’s] knees,” and Atwood’s description of mistresses holding handmaids between their knees during sex and labor.

There are no new ideas in Hollywood the Bible

Don’t think that Bilhah’s story is unique in the Bible. A similar story has been an inspiration to artists for centuries. Abraham, father of Israel, was married to Sarah, reputedly the most beautiful woman in all the world. After a lot of wandering in the desert, Sarah was getting on in years and was still childless. Solution? Offer up her Egyptian handmaid Hagar to do the dirty deed for her.

“I pray thee; go in unto my maid; it may be that I may obtain children by her.” – Genesis 16:3

Hagar by Edmonia Lewis, in the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Edmonia Lewis, a female African American sculptor of the Civil War period, certainly had reason to be interested in the narrative of an enslaved African woman subjected to reproductive abuse. White male European artists had also long been fascinated by the story, possibly more captivated by the bizarre kink factor than issues of subjugation.

Sarah Leading Hagar to Abraham by Matthias Stom, in the Gemaldegalerie.

We’re talking about Western-European art history here, so Hagar is of course an alabaster-skinned blonde. Even Edmonia Lewis used the colorless power of marble to give us a racially ambiguous Hagar. The Bible tells us she was Egyptian. History tells us she may have been black, since Egyptian slaves were typically prisoners of war captured from Nubia and other parts of predominantly black Africa.

Miraculously, Sarah did get pregnant in her old age, and consequently said to Hagar, “Beyotch, get the f#ck out of mah tent!” so Hagar and her son Ishmael were banished into the desert.

Detail of Hagar in the Wilderness by Camille Corot, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Presumably, Hagar is grieving because she and Ishmael are lost in the wilderness, but her face says, “No, I’m pissed off because this is the thanks I get for all the gross old man sex.”

Sally Hemings: An American “Handmaid”

Thomas Jefferson by Mather Brown, in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery (left). This portrait of an eighteenth-century, mixed-race woman (right) gives some idea of what Sally Hemings might have looked like.

Sally Hemings makes a disturbingly cohesive follow-up to the biblical prototype of a captive African woman forced to bear children. Confederate Civil War diarist Mary Chesnut was brutally honest in her assessment of black-white concubinage in the antebellum South, and her association of slavery with patriarchal marriage in Judeo-Christian culture:

“Like the patriarchs of old, our men live all in one house with their wives and their concubines…this is not worse than the willing sale most women make of themselves in marriage…The Bible authorizes marriage and slavery…poor women! Poor slaves!”

Sally Hemings made headlines recently because PBS controversially labeled her as having had a 40-year “relationship” with Thomas Jefferson, whom she bore 6 children. The critics are right that an enslaved person is incapable of a consensual relationship, not to mention that Sally was a minor (by modern standards) when a middle-aged Jefferson started sleeping with her. In the least sinister of a multitude of horrifying scenarios, captive women were coerced into sex with their masters. In the worst cases, they were violently raped. But is it fair to say that Sally’s was the latter case? It should be noted that she chose to leave France, where she was free, to return to Virginia with Jefferson when he promised to free their children. This is not a justification. Slam Poet Clint Smith poignantly asks, “…did you think there was honor in your ultimatum?” The fact that Jefferson never freed Sally herself, even on his deathbed, speaks to a twisted dynamic of control.

This Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray in Scone Palace, attributed to Johann Zoffany, evokes the conflicted situation in which Sally may have found herself. Dido, though not enslaved herself, was the daughter of a British officer and an African slave. This portrait reflects her experience as a beloved, but not quite equal member of an elite white family.

The irony of Thomas Jefferson, who proclaimed in our Declaration of Independence, “all men are created equal,” owning and sexually abusing slaves speaks for itself. We should neither defend nor deny the heinous circumstances of his fathering children with Sally Hemings, but this remarkable woman endured a lifetime of bondage and produced generations of American families. Why not regard her as what she is? One of our founding mothers, as worthy of respect and study as Abigail Adams or Martha Washington.

Is Sally not, in a perverse way, the story of America? Are we a nation founded on freedom, or on concubinage of enslaved women? Michelle Obama is descended from both slaves and slave masters, and as first lady, woke up every day in “a house that was built by slaves,” (the White House). What is that if not a testament to who we are as a nation, at once powerfully inspiring and deeply unsettling. Margaret Atwood’s novel of a crippled American civilization surviving on the backs and bellies of captive women has never been more relevant, yet perhaps it is as much a story of where we are, as where we came from.

Don’t take my word for it, decide for yourself. Tune into The Handmaid’s Tale on Hulu, or better yet, read the book!

By: Griff Stecyk