Horror movies seem doomed to occupy that space on the bottom shelf of human culture, right next to VHS copies of Dude, Where’s My Car, and numerous Twilight paperbacks that have been resold to used bookstores in a mass purge of buyers remorse.

The only occasions when horror films seem to garner an ounce of respect, is when they have been cleverly re-categorized as “thrillers” and marketed as Oscar bait (Silence of the Lambs and Black Swan, we’re looking in your direction). This is somewhat puzzling to the art lover, since horror is perhaps the most complexly visual genre. As such, it is often replete with art-historical references that the critics would rather ignore. This Halloween, we’d like to set the record straight with ten of our favorites moments of classic art in classic horror.

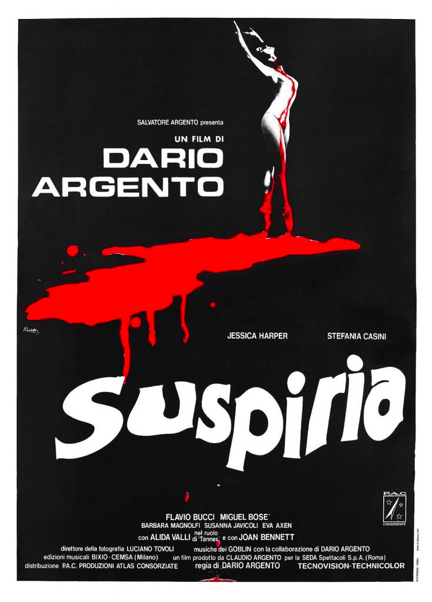

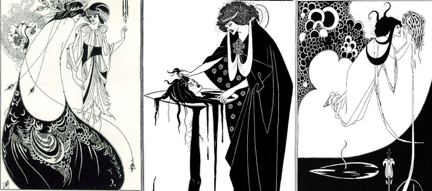

1) Dario Argento’s 1977 Italian cult classic Suspiria is the gory and visually glorious story of a dance school plagued by increasingly violent supernatural disturbances. Doesn’t sound much like a Disney inspired fairytale, but that’s exactly what it is. Not only did Argento cast actress Jessica Harper at least in part because of her resemblance to Snow White but he based the film’s bold primary color palette on 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. He’s less open about the rest of the film’s signature look but any art fan can easily detect obvious references to artists Aubrey Beardsley and M.C. Escher in the disorienting set design, not to mention the dance academy is located on “Escher St.”

Madam Blanc’s office features Aubrey Beardsley inspired wallpaper and wall hangings.

Three illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s 1892 play Salome, visit original prints at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Apartment wall paintings inspired by Escher’s Sky and Water I

2) Frankenstein (1931) was the first horror megahit of the sound era, and is widely considered one the most influential horror movies ever made. Based on Mary Shelley’s timeless novel, Boris Karloff and an iconic makeup job forever immortalized Frankenstein’s monster in the public mind. Today, his image appears on everything from Pez dispensers to Christmas lights.

Mary Shelly was familiar with Henry Fuseli, and was almost certainly influenced by The Nightmare in writing a pivotal scene of the novel.

In one of the few scenes in the film directly lifted from the source novel, we see Dr. Frankenstein’ bride Elizabeth sprawled across the bed with cascading hair, after Henry Fuseli.

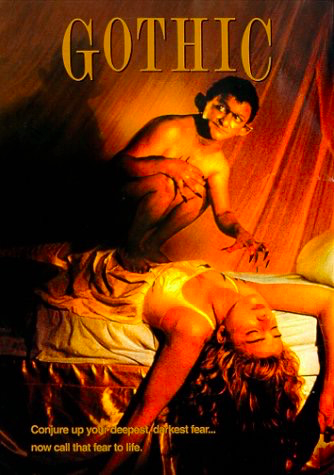

When looking for defining images of gothic horror, it’s hard to beat Fuseli. The Nightmare was later recreated for the poster and set decoration of Ken Russell’s Gothic (1986).

Gothic is a truly bizarre film, loosely based on the night that Mary Shelley conceived of Frankenstein during a hallucinogenic orgy at Byron’s villa. Grainy film stock and surrealist imagery, incongruously paired with elegant period costume and scenery conspire to make a thoroughly unsettling horror biopic.

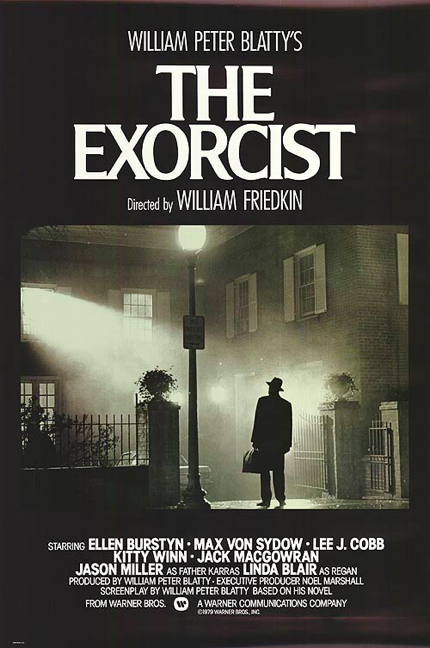

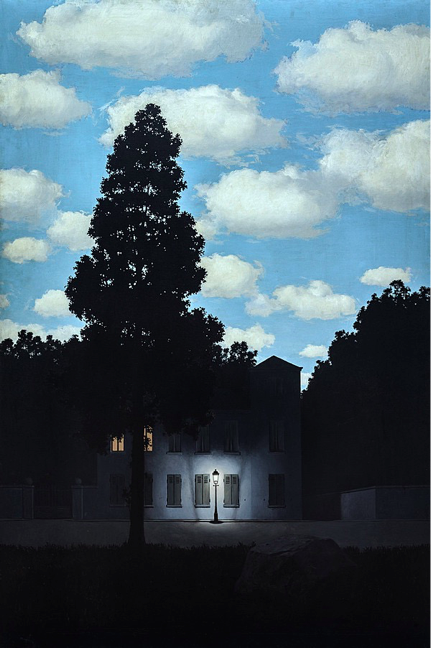

3) 1973’s The Exorcist is a slumber party right-of-passage so scary that it swears many off the genre forever. The story of a young girl who is possessed by the devil and the priest who is sent to save her soul is one of the rare straight-up horror films to ever gain critical acclaim, winning two Oscars and being nominated for eight more. Perhaps this acknowledgment as high art has something to do with its fine art references; the atmospheric movie poster was directly inspired by a series of paintings called Empire of Lights by surreal artist Rene Magritte.

One of three paintings which display houses lit by a single street lamp against a sunlit sky in an attempt to upset the viewer by combining day and night. This piece is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

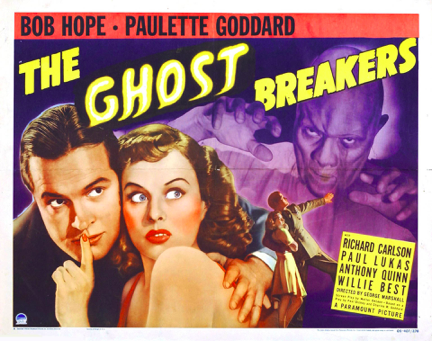

4) The Ghost Breakers (1940), is a horror farce teaming Bob Hope and Paulette Goddard as a couple of unlikely screwballs who unwittingly get mixed up with spooks, voodoo, and even a zombie in a Caribbean castle. The movie delivers a ton of laughs and a few good chills, with its fanciful use of trick photography and makeup effects.

The film also features a prominent Goya reference, with a full-length prop portrait of Paulette Goddard (reputed to be her Spanish colonial ancestor) after two of Goya’s most famous portraits of the Duchess of Alba.

Hope and Goddard in a still from The Ghost Breakers featuring a “Goya” portrait. Note the pointing gesture of the right hand, the white lapdog at her feet, and the black lace mantilla.

Goddard was a major artistic muse of the screen as well, posing for Diego Rivera, and rescuing him from an assassination attempt. A known bisexual, she is also said to have bedded both Diego and Frida Kahlo.

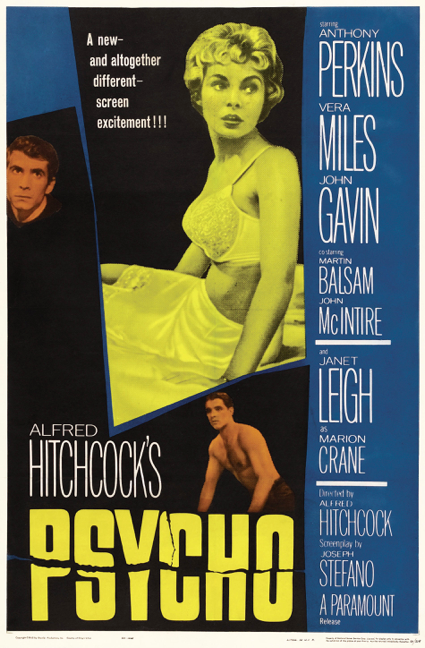

5) The Master of Suspense’s masterpiece, 1960’s Psycho is perhaps one of the most enduring horror films ever made. Considered tame by modern standards, this movie about a mama’s boy who runs a roadside motel had the censors up in arms; a violent shower scene, an unmarried woman in her underwear with a man, not to mention a flushing toilet containing pieces of paper (shocking!) were all cause for panic and have since been cited as important points of erosion in the Production Code Era. As one of the most iconic films of all time (find me a single Introductory film class that doesn’t use the shower scene to demonstrate editing techniques and I truly will be shocked) it’s no surprise that Hitchcock borrows a little from one of the U.S.’s most iconic artists, Edward Hopper of Nighthawks fame. The now notorious Bates Motel was lifted directly from Hopper’s painting The House by the Railroad.

The House by the Railroad is on view at the MoMA.

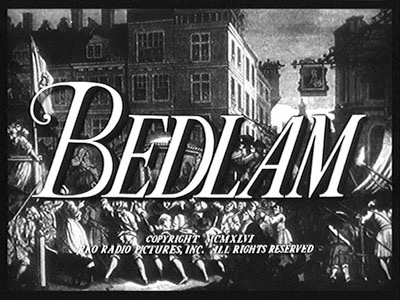

6) Val Lewton took a page out of film noir to produce a series of starkly atmospheric thrillers that scared audiences out of their seats using psychology as an instrument of terror rather than gimmicky monster effects. In Bedlam (1946), he took psychological horror to a new level, setting his film in a literal madhouse. Boris Karloff plays the sadistic warden of the notorious asylum, who subjects his prisoners to mental torture.

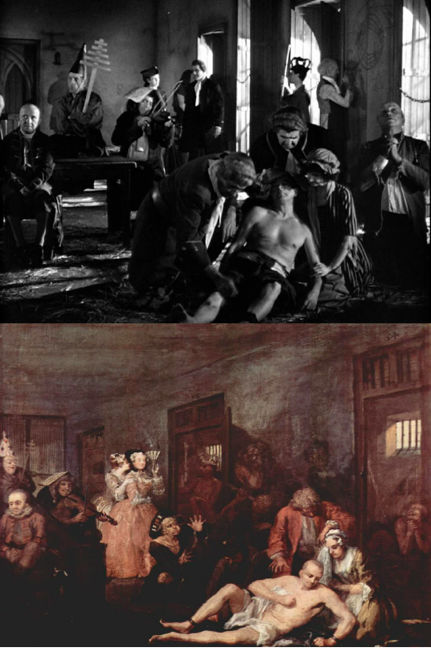

The production designers drew inspiration from William Hogarth’s A Rakes Progress for the films carnivalesque vision of eighteenth-century London. The film opens with a series of engravings by Hogarth, and recreates the composition of The Madhouse.

Opening credits of Bedlam, featuring Hogarth’s engravings.

Scene from Bedlam (top). The Madhouse by William Hogarth at Sir John Soane’s Museum (bottom).

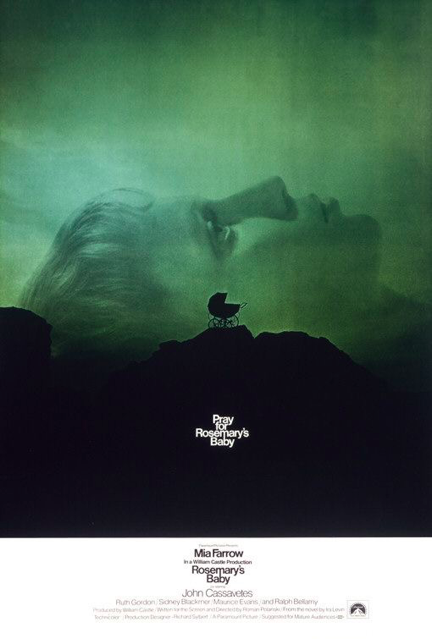

7) As you may have guessed by the title, Rosemary’s Baby (1968) is about a woman named Rosemary and her unborn baby…who may or may not be the seed of Satan (watch the movie to find out). This film, which is more about gaslighting then anything else (honey, the neighbors and I didn’t let the Devil rape you, you’re just hormonal) was extremely well received upon release, giving birth to a string of lesser films regarding witchcraft. It also marked the first Hollywood film of the acclaimed director (despite statutory rape charges) Roman Polanski, a man whose wife, Sharon Tate and unborn child met a bizarre and tragic end when the Manson family stabbed them to death in their Hollywood home.

Though the film didn’t base entire sets or set pieces on famous works of art, the two most pivotal moments in the film use art to deepen the film’s psychology. The extremely disturbing rape scene shows naked Rosemary lying on scaffolding beneath the Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel to show… that God is abandoning her?

In the film’s final scene where Rosemary discovers the truth of the plot she wanders through a dark hallway featuring this Goya painting, which creepily enough shows a witch holding a basket of what appears to be infant parts.

The Witches Sabbath by Goya

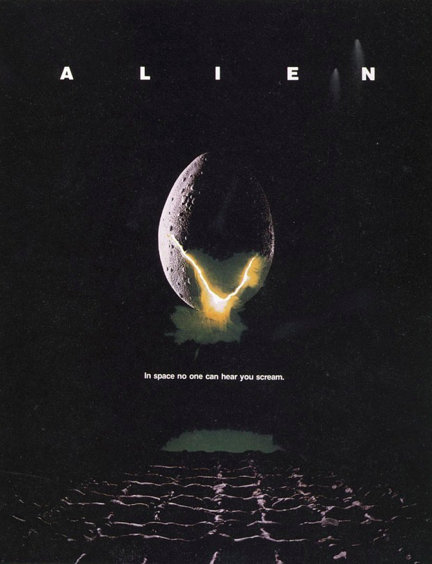

8) Arguably the best horror-scifi film ever made (The Thing could have it beat) 1979’s Alien is a movie about Sigourney Weaver being a badass and kicking alien butt in space. There are other people and characters, but they really don’t matter. What does matter is that Sigourney Weaver is fabulous and that the horrifying aliens known as Xenomorph’s were inspired by art. According to director Ridley Scott he asked artist H.R. Giger to look to paintings by Francis Bacon for inspiration when developing the truly terrifying Aliens. Naturally art inspired by Bacon begat something scary as hell.

The Studies of Figures at the Base of a Cruxifixion is on view at Tate Britain

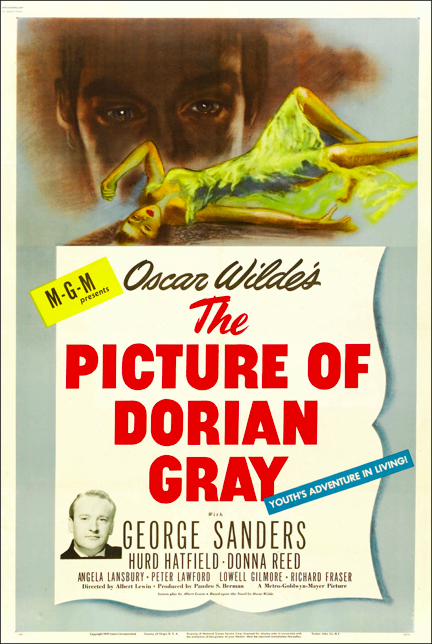

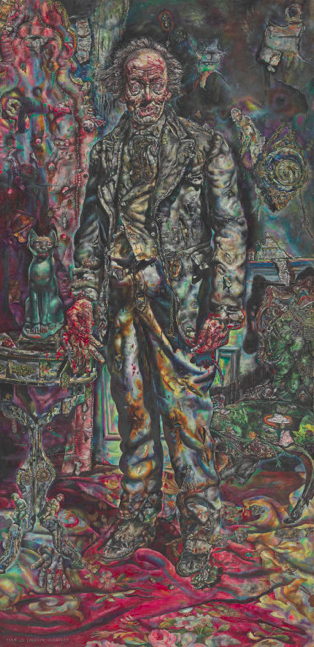

9) Oscar Wilde said, “The only way to get rid of temptation is to yield to it” the 1945 film The Picture of Dorian Gray based on Oscar Wilde’s 1890 novel of the same name demonstrates what happens when you yield too far. The story follows a young man who essentially sells his soul to maintain the visage of eternal youth; he remains beautiful while the wear and tear of all his horrible deeds take their toll on his portrait in the attic. In the final scene of the film (all shot in black and white except for shots of the painting) the audience is treated to an extremely detailed set piece of the pocked and pus-filled portrait. The painting was created for the film by artist Ivan Le Lorriane Albright and it was so good that it made its way into the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Check out my blog for a sinfully good drink to throw back while watching this.

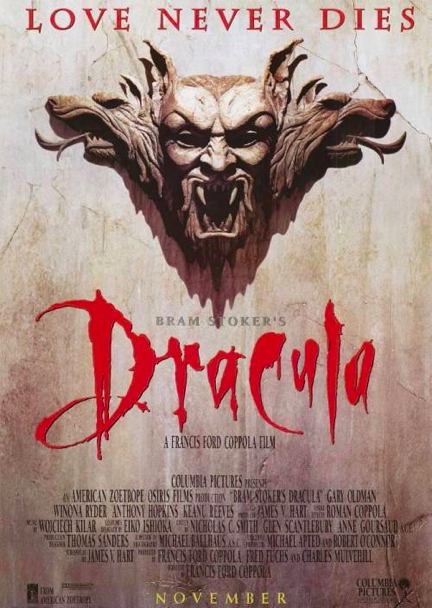

10) 1992’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula may never reach the same level of “classic” as its 1931 counterpart starring THE Dracula, Bela Lugosi, but this stunning Francis Ford Coppola film is without a doubt a modern classic. The all-star cast of Gary Oldman, Winona Ryder, Anthony Hopkins, and Keanu Reeves is overshadowed only by the decadent production design. Bold reds are contrasted by the deepest blacks

In addition to an Oscar winning wardrobe that gives the impression the principal actresses stepped outside of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, the creative team pulled from such sources as sixteenth-century artist Albercht Dürer. Dürer’s self portrait stands in for Gary Oldman as Vlad the Impaler to lend an air of authenticity to the highly stylized production. For once, the original seems to be better looking than his Hollywood counterpart.

Written by Sarah Oesterling and Griff Stecyk