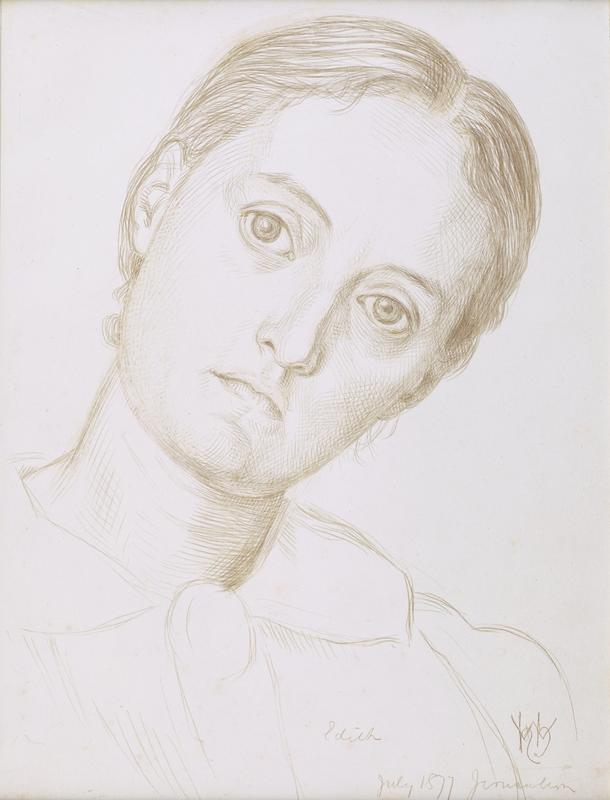

More about The Artist's Wife, Edith Holman Hunt

- All

- Info

- Shop

Editor

This sensitively realized drawing by William Holman Hunt actually depicts his second wife--the sister of his first.

The Pre-Raphaelite heavyweight’s first marriage was to a woman named Fanny Waugh, the daughter of Dr. George Waugh, Queen Victoria’s chemist. In 1866, the year after they married, he and Fanny embarked on a journey to the Middle East. She was pregnant at the time, and did not make it past Florence, where she died of miliary fever shortly after giving birth to their first and only child, a son named Cyril Benoni. After her death, Hunt brought the boy back to England and installed him in the Waugh family residence before heading back out to the Middle East, where he continued to travel to study the landscapes and material qualities of the Holy land to better capture them in his paintings of biblical scenes.

He left young Cyril in the care of the Waughs and returned to visit on occasion (which must have been awkward, since his family blamed him for Fanny’s death). The boy was especially doted upon by Hunt’s sister-in-law Edith, and gradually, upon Hunt’s visits to England, Hunt and Edith fell in love. For a serious-minded man who considered himself morally upright, this may have been a blow, as it was illegal to marry one’s deceased wife’s sister in England at the time. So they traveled to Switzerland and tied the knot there in 1873. It was quite the scandal--Edith’s other sister Alice never spoke to them again. But they remained happily married until Hunt died. Edith seems to have loved him deeply, modeling for him with some frequency and lovingly maintaining their home after his death in memory of him.

According to the script written in Hunt’s hand on the lower right of this drawing of Edith’s face, the image was completed in July 1877 in Jerusalem. The couple traveled across the Middle East together, and while Hunt painted, Edith wrote books about their travels. This particular drawing, a study of Edith’s face, is thought to have been a study for a larger painting of his titled The Triumph of the Innocents, versions of which are housed at the Tate and the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. The painting depicts the flight into Egypt, with Mary riding aboard a donkey and beholding a vision of the souls of all the babies killed by Herod floating alongside her accompanied by "mystic bubbles." Edith’s face would have served as a model for that of the Virgin Mary, which perhaps explains her wide-eyed and somewhat sorrowful expression in this drawing. However, Hunt made numerous other head studies of Edith, and some bear closer resemblance to the painting, indicating that he ultimately decided on a different study as the model. The Triumph of the Innocents occupied him for about ten years, so there was plenty of time for him to change his mind.

What is somewhat interesting is his choice of medium. Hunt used silverpoint for the drawing, an archaic medium that was first used in the fourteenth century but had largely fallen out of use after the Renaissance. A difficult medium to master, silverpoint involves making marks with a silver stylus upon a surface that has been primed with a ground (often made of bone ash or white lead mixed with a binder). The marks the artist makes can not be erased, and over time, the silver oxidizes to create a lovely burnished brown color. Silverpoint was commonly used in the Renaissance, when artists such as Raphael and Leonardo made use of the medium for both preparatory sketches and finished drawings. However, in the centuries following the Renaissance, graphite pencil largely replaced the time-consuming and unforgiving medium, relegating silverpoint to the status of “curiosity” by the 17th century.

Victorian England saw a revival in all sorts of curiosities, however, not least of which was silverpoint. It was part of a renewed interest in Quattrocento art, both among artists and the public, who increasingly had access to the work of the Old Masters through photographs, books, and exhibitions. The British Museum acquired collections of Italian Renaissance drawings throughout the century and publicly displayed them for the first time in 1858, and the Uffizi in Italy, an important pilgrimage spot for many English artists, began displaying their silverpoint collections in 1867. Another factor that played a role in the revival of silverpoint was the first ever English translation of Cennino Cennini’s Libro dell’Arte (Treatise on Painting) in the 1840s, which detailed precisely how to prepare and use silverpoint. Metalpoint sketchbooks with commercially primed paper soon became available on the market, and artists could now dabble in the medium with ease. One major point in its favor was that you could carry the sketchbook with you and your sketches wouldn’t smudge, unlike pencil or charcoal.

As one of the Pre-Raphaelites, William Holman Hunt was intensely interested in emulating the techniques of artists like Leonardo, Holbein, and Raphael, as well as what he considered their spiritual purity. Perhaps it comes as some surprise then that William Holman Hunt was the only member of the first generation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to make use of silverpoint. (Much like Pokémon, the Pre-Raphaelites had a set of generations, and Hunt was a member of the first, the Bulbasaur to Rossetti’s Charmander and Millais’s Squirtle. In the next generation, Edward Burne-Jones would carry the silverpoint torch.) Hunt first used silverpoint in 1869 in a drawing of a gondola. He never used it very often, typically just for sketches and studies like this drawing of Edith. Though he did make some finished pictures in the medium, he mostly used silverpoint to work through problems in pictures, often scratching over his sketches and drawing on top of them. But of course, as someone who was thoroughly convinced that his own way of doing things was the correct way of doing them (he believed he was the only member of the PRB to uphold its principles), when he was old, he complained that modern art students just didn’t take the time to master traditional techniques, notably the preparation of paper for silverpoint, like they used to. A typical “kids these days” complaint.

Sources

- “The Artist’s Wife, Edith Holman Hunt.” Birmingham Museum of Art. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://www.artsbma.org/collection/the-artists-wife-edith-holman-hunt/

- “Mrs. George Waugh.” Cleveland Museum of Art. Accessed May 7, 2021 .https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1984.41

- Bronkhurst, Judith. “William Holman Hunt, O.M., R.W.S. (1827-1910): Pearl.” Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4618892

- Fuga, Antonella. Translated by Rosanna M. Giammanco Frongia. Artists’ Techniques and Materials. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2006.

- Sell, Stacey. ""The Interesting and Difficult Medium": The Silverpoint Revival in Nineteenth–century Britain." Master Drawings 51, no. 1 (2013): 63-86. Accessed May 7, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43705937.

- Sell, Stacey, and Hugo Chapman. Drawing in silver and gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns. London: British Museum, 2015.

- Stonell Walker, Kirsty, and Kingsley Nebechi. Pre-Raphaelite Girl Gang: Fifty Makers, Shakers and Heartbreakers from the Victorian Era. London: Unicorn, 2018.

- Smith, Alison. “Portrait of Mrs. Edith Holman Hunt.” Last modified November 2009. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hunt-portrait-of-mrs-edith-holman-…