More about The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

After contracting a mystery illness which left him permanently deaf in 1792, Francisco Goya’s art took a turn into some seriously dark places.

This shift culminated in his notoriously terrifying Black Paintings (1819-1823), a series which includes his very famous and very creepy painting of the Titan Saturn devouring his own son. Painted directly onto the walls of the rural farmhouse that Goya inhabited in his old age (fittingly named Quinta del Sordo, or House of the Deaf Man), these paintings depicted a bleak vision of humanity, consumed with superstition and violence. Nightmarish visions of demons, witches, goat-headed sorcerers, drowning dogs, and masses of people who just look downright miserable populate them, suggesting that Goya’s mental state during these late years of his life was...not super great. Many have speculated as to why this may be, but we can’t actually know for sure. It’s possible that his deafness and prolonged isolation left him in low spirits, or that he was disillusioned by the horrors of the Peninsular War, as reflected in his iconic painting, The Third of May 1808. Either way, his paintings grew decidedly more disturbing after the 1790s, focusing less on decorous portraits of the Spanish Court and more on images of the supernatural and the grotesque.

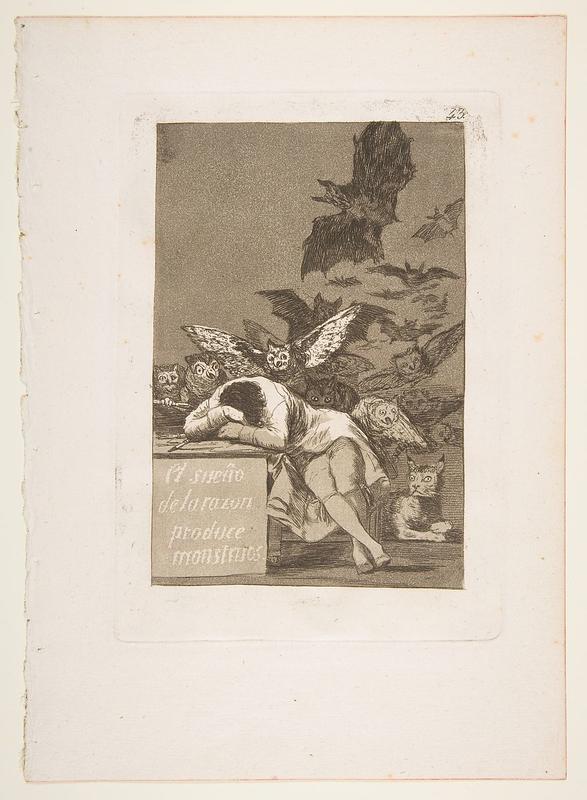

Prefiguring his Black Paintings were his Caprichos, a series of 80 prints, including The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, which were controversial enough to be quickly hushed up by the Spanish Inquisition just two days after their release. In them, Goya sought to critique the many ills he saw as plaguing 18th-century Spanish society, scandalously including disguised versions of real people doing bizarre and horrifying things like holding a farting baby aloft while a crowd looks on (uh, okay), beating human-headed chickens with brooms (sure), and carrying some really smug-looking donkeys around on their backs (why not?).

In the midst of such madness, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters actually looks fairly tame. It’s rumored to be a self-portrait of Goya himself, perhaps hard at work on the very image he’s drawn himself into. Surrounded by a dark, shape-shifting cloud of bats and owls, he slumps at his desk over some loose sheets of paper, possibly asleep, or possibly cowering in fear of his flapping assailants. Meanwhile, a very impatient-looking owl squawks in his ear and tries to hand him a pen as if to say, “Okay, you’ve had your nap, now time to get back to work!”, while its friends bite and claw at poor Goya’s back in an attempt to speed things along. If this is in fact a self-portrait, it seems likely that it’s meant to represent Goya’s own creative process, since he’s depicted himself working on a drawing. And, although the precise meaning of the bats and owls is ambiguous, they appear to be simultaneously tormenting the artist and spurring him on in his work. In other words, Goya has depicted himself here as the quintessential tortured artist, plagued by nightmarish visions which he feels compelled to exorcise through artmaking.

While the figure of the tortured artist might be something of a cliché today, during the Romantic period, when Goya was working, the idea was at the height of its power. The condition of melancholia, as Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 print Melencolia I demonstrates, had been around for a very long time, with roots in the Ancient Greek medical theory of the four humors. Melancholics were thought to contain an excess of the humor black bile, which, according to Hipprocrates, gave people with melancholic temperaments “fears and despondencies,” as well as symptoms like changes in appetite, insomnia, and irritability. These correspond with many of the symptoms which are associated with modern-day clinical depression, suggesting that melancholia may be one of its ancestors.

While the humoral theory of melancholy was still popular in the 18th century, it had also become fashionable by that time to cultivate one’s physical and emotional sensitivity, a trend which is referred to today as the 18th-century “cult of sensibility.” Greater “sensibility” was often linked with a superior intellect and moral character, which in turn led to a new glamorization of melancholy as the condition de rigeur among smart, sensitive, artistic types. This association was carried into the early 19th century, when modern-day psychology was just starting to take shape. “Melancholy” became more clearly delineated as a mental illness with a specific set of symptoms, gradually coming to be associated with male artists and intellectuals. At the same time, women with identical symptoms tended to be labeled as “hysterical” instead, which located their illness in the body (specifically the uterus) rather than the brain. And so the myth of the tortured male artistic genius was born, while women with at least the same level of artistic skill received far less attention than their male counterparts. While the archetype hasn’t quite lost its power, it has been called into question in recent years. Many argue that the myth of the tortured artist is harmful because it suggests that one needs to be mentally ill in order to be truly creative, potentially discouraging people who are struggling with their mental health from seeking treatment out of fear that they might stifle their creativity.

While it is unclear whether Goya himself lived with melancholia (he was a notoriously private person), The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters does provide an interesting illustration of how people may have seen the condition during the Romantic period. The dark cloud of bats and owls hovering over the head of slumped Goya, crowding him and weighing him down, certainly suggest the ruminative thoughts typical of what we now call depression. And the fact that one bat-owl in the top-right corner has actual devil horns on its head invites us to read this etching as a depiction of Goya facing his own inner demons, made literal. But we really can’t know anything about the picture’s meaning for sure. Goya tended to keep things to himself, preferring to hole up alone in his house painting creepy murals of fathers eating their own children rather than open up about his feelings. Either way, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters provides a fascinating window into what Romantic-era psychology may have been like, giving a glimpse into the origins of the tortured artist myth that is still very much with us today.

Sources

- The Art Assignment. “The Myth of the Tortured Artist.” YouTube video, 10:55. October 4, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rv5-O-jP2i8&ab_channel=TheArtAssignment.

- Bahr, Sarah. “Medical deafness or the madness of war: Goya’s motivation for creating the Black Paintings.” Hektoen International: A Journal of Medical Humanities 10, no. 2 (2018). Accessed September 4, 2020. https://hekint.org/2018/03/20/medical-deafn

- Béres-Rogers, Kathleen. Creating Romantic Obsession: Scorpions in the Mind. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

- Dolan, Elizabeth A. “British Romantic melancholia: Charlotte Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets, medical discourse and the problem of sensibility.” Journal of European Studies 33, no. 3 (2003): 237-253.

- Guijarro-Castro, C. “Could neurological illness have influenced Goya’s pictorial style?” Neurosciences and History 1, no. 1 (2013): 12-20.

- Lubow, Arthur. “The Secret of the Black Paintings.” The New York Times, July 27, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/magazine/the-secret-of-the-black-pai….

- MacLean, Robert. “Los Caprichos.” University of Glasgow Special Collections. August 2006. https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/aug…

- Phelan, Stephen. “Goya’s Black Paintings: ‘Some people can hardly even look at them.’” The Guardian, January 30, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jan/30/ goya-black-paintings-prado-madrid-bicentennial-exhibition.

- Schaefer, Sarah C. “Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.” Khan Academy. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/ romanticism/romanticism-in-spain/a/goya-the-sleep-of-reason-produces-monsters.

- Schulz, Andrew. “Satirizing the Senses: The Representation of Perception in Goya’s Los Caprichos.” Art History 23, no. 2 (2000): 153-181.