More about Eagle Peak Trail

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

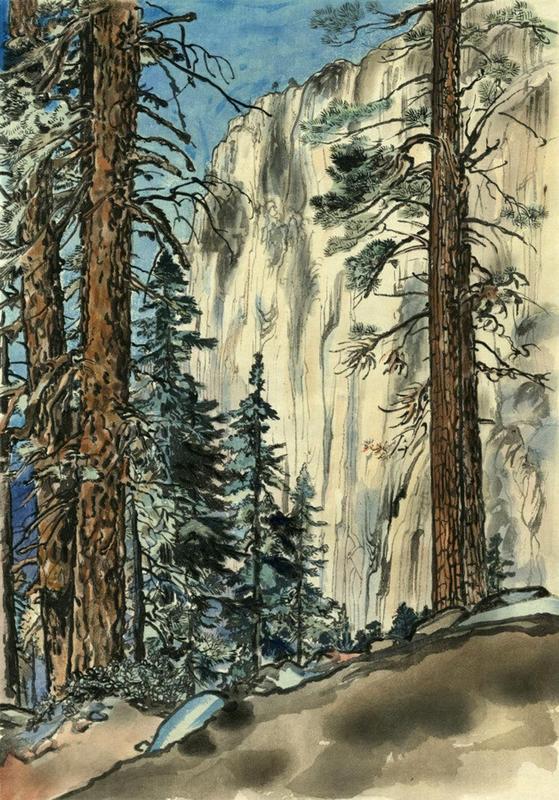

Chiura Obata's Eagle Peak Trail is a meditation on the tradition of Japanese woodblock printing, distinguished to most non-Japanese people by Hokusai's era-defining 神奈川沖浪裏 ("The Great Wave off Kanagawa").

When he made the print in 1930, Obata had been producing work for more than thirty years, but 1930 was the first year that allowed him public acclaim and success. He had just returned from a trip to Japan, where he had shown his earlier works, also depicting Yosemite, to an audience in Tokyo. It was not the first time he made artwork in honor of Yosemite, and his return to Yosemite in search of a spiritual, calm, eternal image may have been a response to the devastating financial events of 1929.

In this pre-WWII period, Obata used tight, strictly controlled brushstrokes, in keeping with his studies of the Japanese and European traditions. Many people remember Obata today for his later work, during and after his incarceration in the internment camps at Tanforan and Topaz. His early work provides a kind of guide to the tradition that he would later revise, revisit and reinterpret with a new openness linked to his fight to keep his family and career together.

Obata was an issei, a first generation immigrant from Japan. He had vivid and emotionally resonant memories of the beauty of the pre-war Japanese landscape, and an encyclopedic understanding of the various schools and periods of Japanese woodblock printing. He also studied European art in Paris, and would eventually teach art at the University of California at Berkeley.

In 1927, his friend Worth Ryder, an art professor at Berkeley, invited Obata to visit Yosemite National Park. The government had evicted the native people, the Ahwahnechee, twice from the park already, but this visit preceded their evictions in 1929 and 1969, and the massive influx of tourism to the park which would begin after WWII.

The Eagle Peak Trail is a difficult six mile trek with a climb of 3,000 feet. In the tradition of John Muir and Jack London, Obata is memorializing the transcendence of this landscape, as if aware of its fragility. His hundreds of artworks from Yosemite have played a key role in both the expansion of the park as a tourist attraction and the protection of its plant and animal life.

As Japan is one of the few nations to have entirely avoided European colonization, it retains a special kind of connection with its history and language, which Obata brings into all of his work.

In his artistic guide "Through Japan with Brush and Ink," Obata introduces us to Japanese names for mountains, streams and other figures of the outdoors, in the hopes that the untranslated words will capture the emotional energy of the practice more accurately. For example, he writes, we often refer to Mount Fuji as Fuji-san, affixing an honorific suffix to the name of the mountain, in a mode of honorific speech called keigo (敬語). さん, -san, is the most common honorific, and it is almost universally used among speakers of equal social status. Calling the mountain Fuji-san evokes the sense of respect and holistic awareness that indigenous people of most places tend to offer to mountains and other monuments of the earth. It is this awareness that Obata brings to Eagle Peak, and incorporates into the print.

Sources

- "Chiura." Behind the Name. https://www.behindthename.com/name/chiura/submitted. (Accessed September 5th, 2019).

- Lee, Jennifer. "Solving a Riddle Wrapped in a Mystery Inside a Cookie." The New York Times. Jan. 16, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/16/dining/16fort.html.

- Means, Sean P. "Chiura Obata, who painted natural wonders and hardships of Japanese-Americans at Topaz, gets major exhibition at Utah Museum of Fine Arts." The Salt Lake Tribune, May 25, 2018, https://www.sltrib.com/artsliving/arts/2018/05/25/chiura-obata

- Obata, Chiura.Through Japan with Brush and Ink (North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publishing, 1990).

- Schaffer, Jeffrey P. "One Hundred Hikes in Yosemite," Gorp.com. https://web.archive.org/web/20140528045059/http://www.gorp.com/parks-gu…. (Accessed September 5th, 2019).

- Schultz, Charles M. "Paper Planes: Art from Japanese American Internment Camps." Art in Print 5, no. 3 (September-October 2015).