More about Chiura Obata

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

Chiura Obata, 小圃 千浦, ran away from home to avoid military service as a teenager, immigrated to the U.S., studied art in Paris, and became an art professor in Berkeley.

The rest of his life was marked by the same adventurous, wandering sensibility and firm commitment to principle. His wife Haruko Kohashi was one of the first to introduce ikebana, the formal art of flower arrangement, to the U.S.

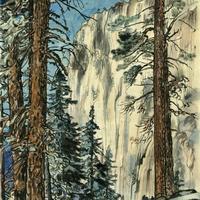

Wartime executive orders incarcerated Obata, his wife, their children, 110,000 other people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, and even a few thousand Germans, Italians, and Jews, in internment camps. Although Obata's colleagues and supervisors at the University of California appreciated his service as a professor for the previous ten years, they could only offer to store his artwork, and could not prevent the closing of the family's art store on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. The order could have easily destroyed his career and his legacy. The bombing of Pearl Harbor supposedly led the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to devise the order, although that rationale makes no sense, because none of the people of Japanese descent in Hawaii, where Pearl Harbor is located, were incarcerated. The order was an ignorant and tragic re-emergence of the virulent xenophobia and cruelty which lay just under the surface of a country struggling for a sense of cultural and spiritual self-definition. It is only through the power of Obata's character and his dedicated spirit that he was able to use this horrific experience to maintain a unique and beautiful signature style whose influence is active among many artists today.

Like Kahlo's bus accident, it introduced such extreme difficulty to the artist's life that he had no choice but to return to his art with a different perspective, using his art as a form of survival, drawing while on crowded, noisy buses and trains from one internment location to another, and even establishing art schools at two internment camps, Tanforan and Topaz.

Eight thousand U.S. residents of Japanese descent were incarcerated at Topaz in Utah. Amy Lee-Tai writes, "When Obata was released early from Topaz, my grandfather took over as director of the art school. My grandmother taught classes to children; my mom and uncle were students. The art school gave them all a sense of purpose and peace behind barbed wire."

Amidst the chaos, violence and privation of the camps and detention center, Obata found sixteen other incarcerated professional artists to organize and assist in the art schools at Topaz and Tanforan. Ths schools taught at least twenty-six subjects, including ikebana, and enrolled and instructed 600 students.

Obata's work has influenced several generations of artists and scholars, including his son, the prominent architect Gyo Obata, and his granddaughter, the author and historian Kimi Kodani Hill.

Sources

- "Exclusion: The Presidio’s Role in WWII Japanese American Incarceration." The Presidio Trust. Mar. 2, 2017. https://www.presidio.gov/presidio-trust/press/exclusion-the-presidios-r….

- Hill, Kimi Kodani. Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata's Art of the Internment (Berkeley: Heyday, 2000).

- Lee-Tai, Amy. "Topaz Museum: A Gem in the Desert." Amy Lee-Tai: Children's Book Author. https://amyleetai.com/tag/topaz-art-school. (Accessed September 5th, 2019).

- Matsumoto, Nancy. "Art and the Creation of a Resilient Japanese American Spirit." PBS SoCal. May 21, 2019, https://www.pbssocal.org/kcet-originals/artbound/art-creation-resilient….

- Means, Sean P. "Chiura Obata, who painted natural wonders and hardships of Japanese-Americans at Topaz, gets major exhibition at Utah Museum of Fine Arts." The Salt Lake Tribune. May 25, 2018, https://www.sltrib.com/artsliving/arts/2018/05/25/chiura-obata

- "'Momotaro,' a folk tale and Kibiji district." Discover Okayama of Japan. https://web.archive.org/web/20120522182456/http://okayama-japan.jp/en/h…. (Accessed September 5th, 2019).

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Chiura Obata

Chiura Obata (小圃 千浦, Obata Chiura; November 18, 1885 – October 6, 1975) was a well-known Japanese-American artist and popular art teacher. A self-described "roughneck", Obata went to the United States in 1903, at age 17. After initially working as an illustrator and commercial decorator, he had a successful career as a painter, following a 1927 summer spent in the Sierra Nevada, and was a faculty member in the Art Department at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1932 to 1954, interrupted by World War II, when he spent a year in an internment camp. He nevertheless emerged as a leading figure in the Northern California art scene and as an influential educator, teaching at the University of California, Berkeley, for nearly twenty years and acting as founding director of the art school at the Topaz internment camp. After his retirement, he continued to paint and to lead group tours to Japan to see gardens and art.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Chiura Obata