More about American Gothic, Washington, D.C., 1942

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

The clever title of American Gothic, Washington, D.C., by Gordon Parks references another famous artwork.

It recalls Grant Wood's 1930 painting American Gothic, a work which shows the resemblance between the austere and mournful faces of an Iowa couple and their Carpenter Gothic house in the background. Wood found it to be "a form of borrowed pretentiousness, a structural absurdity, to put a Gothic-style window in such a flimsy frame house." By the time Parks developed his negative of the photo American Gothic, Washington, D.C., Grant Wood's work was popular and famous, with an implicit coastal wink and a nudge ridiculing rural people. Although Wood didn't want it to be a satire, per se, the critics read it as one. As a satire of a "satire," however, Parks's photo is 120% serious.

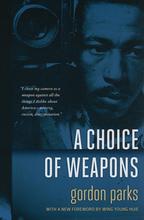

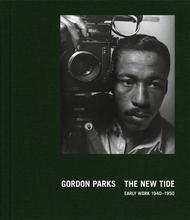

As he recounts in his classic memoir, A Choice of Weapons (1967), Parks traveled a long, winding and perilous path from segregated schools (and segregated everything else) in Fort Scott, Kansas, where his parents, Sarah and Jackson Parks, grew "corn, beets, turnips, potatoes, collard greens, and tomatoes," long before local polyculture was cool. The recipient of a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, by the time of this work Parks had found employment as a photographer with Roy Stryker of the Farm Security Administration in D.C. Parks, just over a decade before he shot this photo, had been beaten by his brother-in-law and kicked out of his brother-in-law and sister's house, surviving in the bitter cold of Minneapolis by riding the passenger trains from one end of the line to the other. This humiliating period gave him a lifelong interest in the lives of poor people in the US.

Another abiding interest was in the functionaries of government and business, the "Fat Cats," as it were, almost exclusively self-identified white men, like the scotch-sipping fellas sitting in the "overstuffed chairs" at the hotel where Parks served as a bellboy, who didn't see Parks as another man, but rather as "a sort of dark ectoplasm that only materialized when their fingers snapped for service." It seems as though the young Parks has a whole choir of angels guarding him when, like his most famous character Shaft, he pistol-whips a white Chicago flophouse owner for his back pay, and for calling him a "black bastard." Parks was, as it were, a baaaaad dude.

Years later, Parks yearned to show Stryker images of the kind of servitude he'd known in his teens, but it was tougher than he thought it would be. Stryker pointed out a "Negro charwoman" cleaning the hallway outside of his office, and suggested that Parks talk to her. After Stryker went home for the day, Parks tracked her down in a notary public's office. Her name is Ella Watson, and she "was a tall, spindly woman with sharp features…and a sharp intelligence shone in the eyes behind the steel-rimmed glasses." At first, because she didn't know what Parks wanted, "it was a meaningless exchange of words. Then, as if a dam had broken within her, she began to spill out her life story." Having lost her father to a lynch mob, Watson subsequently buried her mother, husband, and daughter, leaving her with two kids, one of them suffering from a paralytic condition, who were cared for by various neighbors while the single Watson was at work. Her government salary was $1,080 per year, approximately $17,102 in 2020 purchasing power. By recording these facts, Parks overturns the centuries-old tradition of artists not giving a rat's tucchus-hair about the names of their genre subjects, especially the black sitters.

Parks said of this work: "My first photograph of her [American Gothic, Washington, D.C.,] was unsubtle. I overdid it and posed her, Grant Wood-style, before the American flag, a broom in one hand, a mop in the other." Critics tend to disagree—they praise this work (which Stryker rejected) for its honesty and directness. Stryker said, "this can't be published, but it's a start," but Parks went ahead and published it in the left-leaning PM newspaper anyway. Early on in A Choice of Weapons, Parks narrates his constant anger like a Chester Himes character. Later, however, surprised by the courtesy of a white southerner, Parks recalls the teachings of his late mother, which guide him in every day of his life, and her refusal to allow him "to take refuge in the excuse that I had been born black." The tension between the need to face the injustices of racism and white identity politics head-on, against the need not to rely on his blackness as an "excuse," leads to an ambivalence that may explain Parks criticism of one of his most famous photos, but which also may have compelled him to become one of America's great artists, thoughtfully exploring the complexities and contradictions of the US through his photographs.

Sources

- Fleetwood, Nicole R. Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Garwood, Darrell. Artist in Iowa: a life of Grant Wood. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1971.

- Greer, Brenna Wynn. Represented: The Black Imagemakers Who Reimagined African American Citizenship. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

- McDannell, Colleen. Picturing Faith: Photography and the Great Depression. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Monnet, Agnieszka Soltysik. The Poetics and Politics of the American Gothic: Gender and Slavery in Nineteenth-Century American Literature. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Parks, Gordon. Voices In The Mirror: An Autobiography. New York: Harlem Moon, 2005.

- Webster, Ian. "$1,080 in 1942 is worth $17,102.10 today." Official Data Foundation, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1942?amount=1080.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about American Gothic (photograph)

American Gothic (also known as American Gothic, Washington, D.C.) is a photograph of Ella Watson, an American charwoman, taken by the photographer Gordon Parks in 1942. It is a reimagining of the 1930 painting American Gothic by Grant Wood.

Time magazine considers American Gothic one of the "100 most influential photographs ever taken".

Check out the full Wikipedia article about American Gothic (photograph)

I really like the way that the artist uses the lines of the flag in the background as a way to bring your eye to the woman in the middle of the photo. Also, I like how it is in black and white. This is typical for the time period that it was shot in, but it also has a seriousness to it by bringing emphasis that African Americans were there to be slaves and work for the people that 'owned' them.