More about George Grosz

- All

- Info

- Shop

Works by George Grosz

Contributor

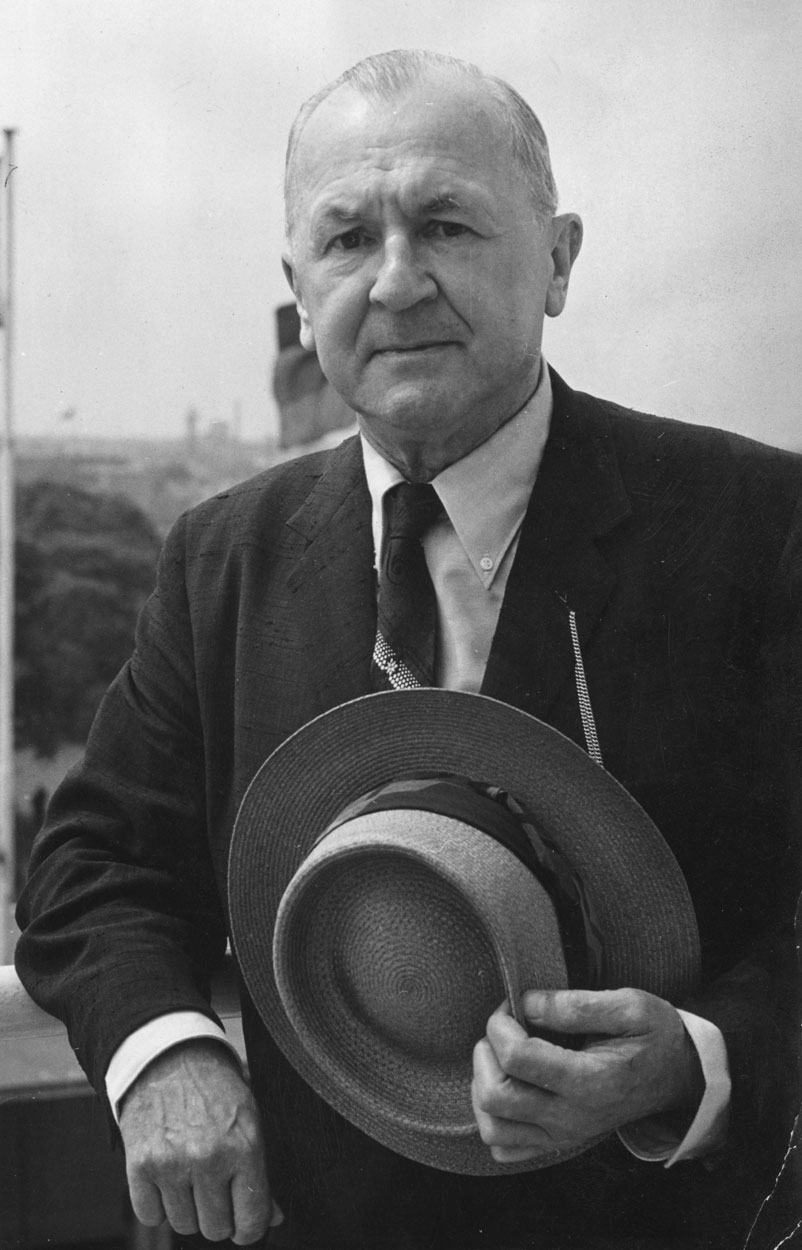

Born Georg Ehrenfried Groß to practicing Lutherans on July 26, 1893, Groß Anglicized his name to George Grosz in 1916, marking on paper his disillusionment with the militarism of Weimar, Germany.

As you can imagine, the less-than-cheery rapport between artist and State only grew in the following decade and a half, by the end of which the State was so fed up with Grosz that the artist left his home, where he'd built a name for himself as a prominent satirist with a brilliant sense of confrontational, biting irony, for New York City. Although the artist's decision to get out of fascist dodge was wise, and came not a moment too soon, especially with the rise of a certain mustachioed ex-artist dictator who Grosz, not wanting to honor him, called simply a "weird little man," Grosz faced many challenges Stateside. He finally returned to Berlin as a senior citizen in 1959, with his "tail between his legs," in his son's words.

To outside observers, Grosz had no reason to be ashamed of his accomplishments in the U.S. He'd founded his own art school in a chic part of Manhattan, where he could simultaneously watch the "idlers sitting on newspapers on the sidewalk and the rich idlers on Fifth Avenue," the rich ignoring the poor as if they belonged to a different galaxy. This distinction between haves and have-nots, and the profound feeling of injustice that it aroused in Grosz, connects his work with that of his friend, fellow communist playwright Bertolt Brecht, whose stage once displayed Grosz's most controversial work, one depicting a crucifixion of a soldier. This work got Grosz in legal trouble on blasphemy charges, which he eventually beat, although he faced several other cases before he left Germany.

Grosz taught at the Art Students' League of New York, driving his own automobile, wearing the finest suits, and greeting his white-haired secretary in the morning, for whom Grosz said, like everyone in the U.S., somehow "it was always a nice day." Maybe this perpetual cheeriness was connected to the business-oriented nature of the society—in his words, in the U.S., nobody cares about what you do for a living, only how much money you make. This fact, along with Grosz's disgust with war, his own traumatic memories of serving in the military and his subsequent psychiatric hospitalization, and his perennially excessive drinking, made Grosz, sadly and self-deprecatingly, repeat the old adage, "those who can, do, those who can't, teach." But I can do! Grosz protested, practicing his brushstrokes with his own handmade watercolor brushes for half an hour every morning before starting work. Grosz was prolific, producing around 450 paintings and more than 15,000 works on paper. Like Cézanne, he did what he could to minimize social contact in his studio, even answering the door in the guise of a servant, telling guests, "I'm sorry, but Mr. Grosz isn't here."

While his wife, Eva, tuned in to the Apollonian sounds of Mozart and Bach on the radio, Grosz's son says, George would sing cabaret melodies and listen to jazz music, which he loved. His son remembers playing the guitar while he and Pops listened to jazz over glasses of wine, gulped by the artist between cigar puffs. Eventually, George would start to cry, saying to his son, "I wish I could do that." "Too much vino," Grosz the Younger says.

Grosz's son and daughter-in-law, Martin and Lillian Grosz, recently sued the Museum of Modern Art and other museums, accusing them of illegally appropriating Grosz's work. They wrote in their statement for the MoMA case that although George Grosz "was not a Jew, his work typified" the kind of "degenerate art" that threatened the fascists, which is absolutely true, but, because of the statute of limitations, the court granted the defendant's motion to dismiss the case. Strangely enough, the confrontational brilliance and relentless pace of his work made him a Jew in the eyes of his many haters—he once received an iron pipe in front of his studio with a note: "if you keep on like this, this is for you, you old Jewish pig." From German museums alone, the regime stole 285 Grosz works, seventy of which are, sadly, still missing. The executor of the artist's estate, Ralph Jentsch, seeks to compensate the artist for the injustice enacted on him by the fascists. They "plunged him into trouble," Jentsch says.

Still, Grosz's legacy continues through his own work and that of his students and children. He taught, for example, James Rosenquist, Romare Bearden, and Jackson Pollock. His son, Martin Grosz, is jazz musician, and another son, the late Peter Michael Grosz, was a prominent aviation historian.

Sources

- Conrad, Andreas. "George Grosz: Maul halten und weiterdienen!" Der Tagesspiel, Jul. 7, 2001, https://m.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/george-grosz-maul-halten-und-weiterdie….

- "George Grosz in America." YouTube video, 1:33:05. Mar. 3, 2018, https://youtu.be/TB-V6TB9NA4.

- "Grosz v. Museum of Modern Art, 772 F. Supp. 2d 473 (S.D.N.Y. 2010)." CourtListener, Mar. 3, 2010, https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/2472738/grosz-v-museum-of-modern-….

- Grosz, Marty. "Biography." Marty Grosz, http://martygrosz.com/biography.htm.

- Jentsch, Ralph. George Grosz: Berlin-New York. Milan: Skira, 2008.

- Parfait, Claire, Hélène Le Dantec-Lowry, and Claire Bourhis-Mariotti. Writing History from the Margins: African Americans and the Quest for Freedom. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2016.

- Sontheimer, Michael. "Vertriebene Bilder." Der Spiegel, Mar. 23, 2009, https://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-64760925.html.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about George Grosz

George Grosz (/ɡroʊs/;

German: [ɡʁoːs] ⓘ; born Georg Ehrenfried Groß; July 26, 1893 – July 6, 1959) was a German artist known especially for his caricatural drawings and paintings of Berlin life in the 1920s. He was a prominent member of the Berlin Dada and New Objectivity groups during the Weimar Republic. He emigrated to the United States in 1933, and became a naturalized citizen in 1938. Abandoning the style and subject matter of his earlier work, he exhibited regularly and taught for many years at the Art Students League of New York. In 1959 he returned to Berlin, where he died shortly afterwards.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about George Grosz