More about Miss Elizabeth Haverfield

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

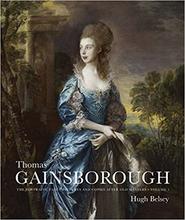

As Gainsborough entered his last few years, his Portrait of Miss Haverfield shows both the confidence and the free sense of abstraction that he had acquired over his amazing career.

The subject of this portrait, Elizabeth Anne Haverfield (1776-1817), is around eight or nine years old. She is the daughter of John Haverfield, gardener of the Richmond Pleasure Gardens at Kew and resident of Haverfield lodge, where the portrait lived until 1850. It was bequeathed to the Crown in 1897 by Lady Julie-Amélie-Charlotte Castelnau Wallace, who inherited it from her father-in-law, Captain Richard Seymour-Conway, 4th Marquess of Hertford. If you haven't noticed, the more names you have, the more noble you are. The somewhat spontaneous feeling in this painting, as if a real moment had been captured as the child played with the ribbons on her coat, may point to Gainsborough's habit of drawing inspiration from his everyday life. If he "found a character he liked" on one of his walks, Sir Joshua Reynolds writes, "and whose attendance was to be obtained, he ordered them to his house" for a portrait.

Like the unibrowed infant Gerald Samson and Maggie Simpson, Gainsborough and Reynolds had once been serious rivals, but, as the two contemporaries aged, Reynolds warmed to Gainsborough and began to record some valuable information key to understanding Gainsborough's distinctive methods. Reynolds' writing on Gainsborough is a sweet and heartfelt obituary to the rival who became his friend in his last few weeks.

"If any little jealousies had subsisted between us," Reynolds writes, "they were forgotten, in those moments of sincerity." Gainsborough recognized that Reynolds was worthy of hearing his opinions on art by "being sensible of his excellence." Reynolds remarks that Gainsborough composed his works holistically, all at once, so that they achieved a kind of general consistency and purpose. As if painting wasn't challenging enough already, Gainsborough had a habit of using six-foot-long brushes, so that he could see the overall composition in a way that approximated the first impression of a visitor to a gallery. After all, you only get one chance to make a first impression.

Sources

- Brock-Arnold, George Moss. Gainsborough. London: Sampson Low et al., 1881.

- Darley, Gillian. John Soane: An Accidental Romantic. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Kew Bulletin, Volume 5. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1891.

- "Miss Elizabeth Haverfield." ArtUK, https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/miss-elizabeth-haverfield-209466.

- "Miss Elizabeth Haverfield." The Wallace Collection, https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=direc…

- Reynolds, Joshua. The Works Of Sir Joshua Reynolds...Containing His Discourses, Idlers, A Journey To Flanders And Holland...In Two Volumes. To Which Is Prefixed An Account Of The Life And Writing Of The Author, By Edmond Malone, Volume 1. London: Cadell,

- Schierz, Carina. Die Simpsons, Springfield und die USA: Was wirklich hinter der gelben Kleinstadt steckt. Marburg: Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag, 2013.