More about Greenwood, Mississippi

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

William Eggleston sure knows how to make you feel anxious without seeming to try.

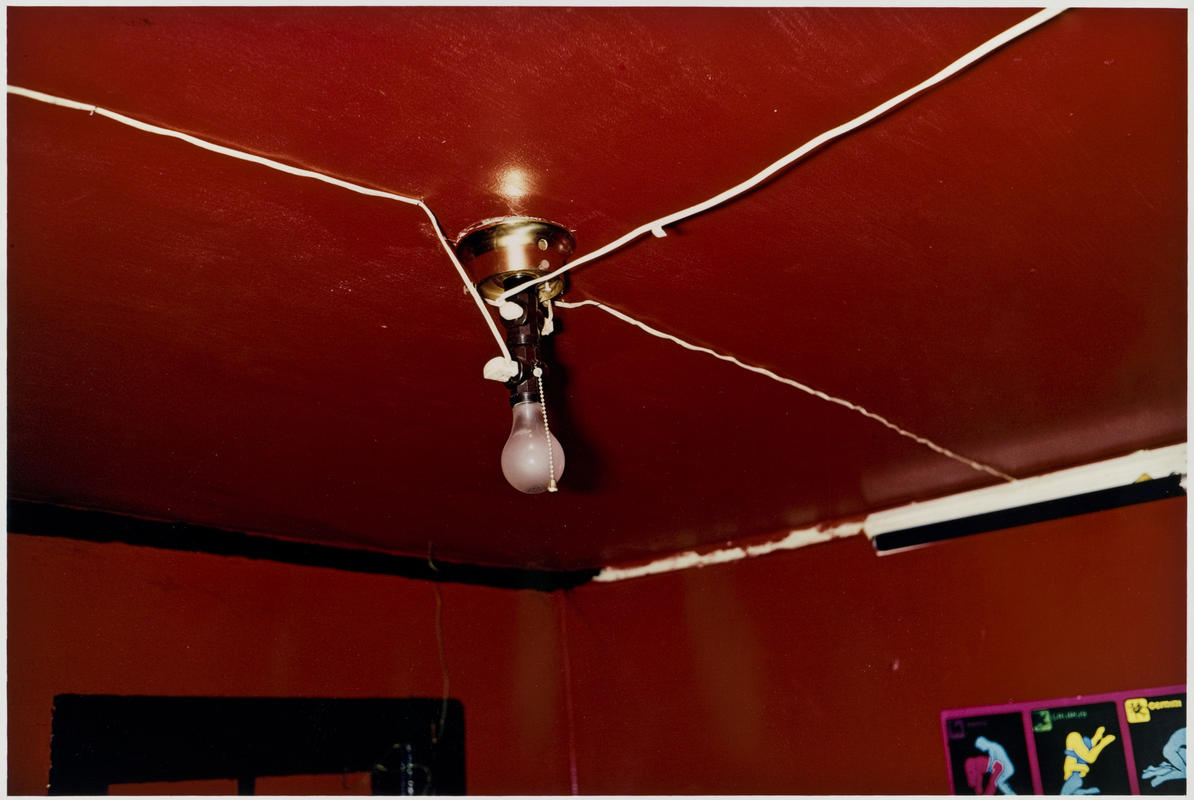

Maybe it’s the glaring red of the walls and ceiling – somehow even more red than Matisse’s Red Studio – that is strange. Or maybe it’s the sliver of the pornographic poster poking out of the corner. Whatever it is, Eggleston crammed lots of feeling into this photograph, even when using the least amount of subject matter possible. Nothing that Eggleston photographs happens by accident, though. In fact, he embraces the unsettling nature of this scene. Eggleston has described the colors in this photograph as being like fresh blood on a wall, and that definitely doesn’t make me feel warm and fuzzy.

Eggleston didn’t invent color photography by any means, but he made it relevant for fine art photographers. Prior to Eggleston’s innovative photographs that debuted in full color, color photography was primarily used for advertisements. The bright colors were guaranteed to catch your eye in hopes of selling you something. Eggleston must have thought he could do the same with fine art photographs. Much to everyone’s chagrin, he was right. By the mid-1960s, Eggleston had all but abandoned the class black-and-white shots traditionally associated with the photographic medium.

As a pioneer of color photography, Eggleston had to make sure that he was doing it right. To get others on board, Eggleston utilized bold colors that bordered on garish. To do so, he chose the dye transfer process, in which separate cyan, magenta, and yellow layers are placed on top of one another to create an almost impossibly vibrant print. Adapted from advertisement printing, dye transfer was the perfect printing method to demonstrate the shocking possibilities of color photography. Eggleston would prefer that you see this picture in person as a dye transfer print, rather than as an image in a book, so that you get the full effect.

But this wasn’t the only way that Eggleston defied tradition. Gone were the days of regal landscapes by Ansel Adams and ethereal shots by Alfred Stieglitz. Instead, Eggleston photographed the boring and the banal, reveling in how he could illuminate the most common elements of the everyday world. At least that’s how the critics reviewed his first debut show. For Eggleston, on the other hand, the everyday was extraordinary. There is no hierarchy of importance in his subject matter. He photographs everything, treating every subject the same, no matter if it’s a person, a tricycle, or a ceiling. His photographs have the same documentary quality that can be found in a photograph by Diane Arbus – just in glaring Technicolor. Eggleston used color as a language to help him speak about the nature of contemporary life in the American south, where he was born and bred. Based on the almost violent feeling of this bizarre, red scene, we can guess his thoughts on the subject.

Sources

- Burroughs, Augusten. “William Eggleston, the Pioneer of Color Photography.” The New York Times Style Magazine. The New York Times. 17 October 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/17/t-magazine/william-eggleston-photogr…. Accessed 9 May 2022.

- Churchman, Fi. “Looking at Pictures with William Eggleston.” ArtReview. Features. 13 May 2019. https://artreview.com/ar-may-2019-feature-william-eggleston/. Accessed 11 May 2022.

- Cotter, Holland. “Old South Meets New, in Living Color.” The New York Times. Art & Design. 6 November 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/07/arts/design/07eggl.html. Accessed 9 May 2022.

- Hostetler, Lisa. “The New Documentary Tradition in Photography.” In The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ndoc/hd_ndoc.htm. Accessed 20 May 2022.

- J. Paul Getty Trust. “William Eggleston.” Getty Museum Collection. https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103KDK. Accessed 11 May 2022.

- Museum of Modern Art. “Dye transfer print.” Art terms. https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/dye-transfer-print. Accessed 20 May 2022.