More about Dancers Practicing at the Barre

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

I wonder what Degas would think about barre being the hottest new workout trend.

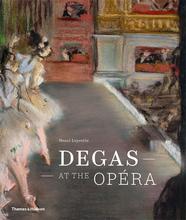

He’d probably think that the women in these classes are a touch too old for his taste. Let’s be honest – Degas’s interest in young ballerinas is questionable at best. His oeuvre includes over 1,500 depictions of dancers in a multitude of media. His visual experiments depicting dancers and their fleeting movements earned him the name of Impressionist, which he all but scorned. But he didn’t really fit in anywhere else, especially not at the Salon. I guess beggars can’t be choosers because Degas debuted this painting at the Third Impressionist Exhibition of 1877, where other instantly-famous works such as Renoir’s Dance at the Moulin de la Galette also appeared for the first time. With the generous financial help of Gustave Caillebotte, the Impressionists rebelled against the establishment and made their beliefs about art known, despite their rejections from the Salon.

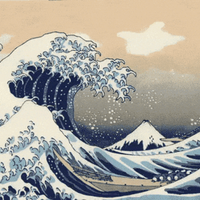

It might not seem like a big deal now, but Degas obsessed over the watering can in this painting. Although you might see more Nalgenes than watering cans at your local combination barre and pilates studio today, nineteenth-century dancers commonly watered their studio floors to keep dust from rising as the ballerinas pranced and pliéd around the studio. Through clever cropping, the watering can is also a visual joke, as it mirrors the body language of the dancer on the right.

After the painting ran its course in the Third Impressionist Exhibition, Degas gave it to the collector Henri Rouart to replace an earlier work that the artist accidentally destroyed after attempting to alter it – just like the well-intentioned woman that botched the Ecce Homo in Borja, Spain. Known for being obsessive Degas also later thought twice about the watering can and actually asked Rouart if he could rework the painting. Rouart had learned his lesson, however, and declined the request, which was probably for the best.

Art collector Louisine Havemeyer bought this painting from Rouart’s estate sale in 1912 for $95,700, a record price for a work by a living artist. The Met then quickly acquired this hot-button work in 1929 in the huge Havemeyer bequest, which donated over 2,000 artworks to the museum.

Sources

- Blakemore, Erin. “Sexual Exploitation was the Norm for 19th Century Ballerinas.” History. 22 August 2018. https://www.history.com/news/sexual-exploitation-was-the-norm-for-19th-…. Accessed 1 October 2019.

- Freedmen, Danielle. “The Secret Sexual History of the Barre Workout.” The Cut. https://www.thecut.com/2018/01/barre-workout-sexual-history.html. Accessed 1 October 2019.

- Frelinghuysen, Alice Cooney, Gary Tinterow, Susan Alyson Stein, Gretchen Wold, and Julia Meech. Splendid Legacy: The Havemeyer Collection. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993.

- Gersh-Nesic, Beth. “The Eight Impressionist Exhibitions from 1874-1886.” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/the-eight-impressionist-exhibitions-183266. Accessed 1 October 2019.

- Gompertz, Will. What Are You Looking At? New York: Penguin Group, 2013.

- Midgett, Anne. “Degas defies limits in ‘Dancers at the Barre.” The Washington Post. 29 September 2011. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/degas-defies-limits-in-d…. Accessed 30 September 2019.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Dancers Practicing at the Barre.” Collection. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436139. Accessed 1 October 2019.

- Trivium Art History. “Dancers Practicing at the Barre.” Artists. https://arthistoryproject.com/artists/edgar-degas/dancers-practicing-at…. Accessed 1 October 2019.