More about Tu m’

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

Tu M' is Marcel Duchamp’s satirical sign-off to his painting career.

Marcel Duchamp lived to challenge preconceived notions of what “art” is to others. So, in his last canvas painting he created before distancing himself from a type of art he’d grown to despise, he put it all out there, literally, figuratively, and as sarcastically as possible.

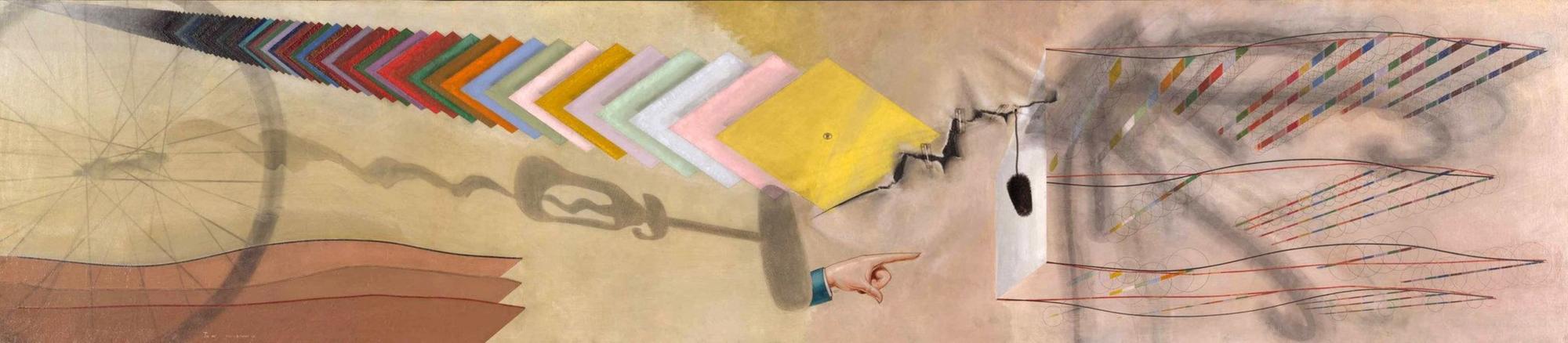

One particular aspect of canvas paintings done by his contemporaries that Duchamp wasn’t fond of was illusionism. In opposition to representational painting, Duchamp was known for his pieces called “ready-mades." For example, Bicycle Wheel, a sculpture made of a bicycle wheel simply mounted on a kitchen stool. In Tu m’ he threw in three shadows of his ready-mades, a layer of commentary eluding to his past works that utilized real, everyday objects, ironically rendered in this painting via illusionism.

Duchamp himself referred to the piece as less of a painting and more an inventory of his past work. (He also mentioned he wasn’t a fan of it, but I digress.) The three ready-mades shown through shadow are the aforementioned Bicycle Wheel, Hat rack, and the third is a corkscrew that Duchamp spoke of but was never exhibited publicly. The two-foot long bottle brush he put in the canvas tear is also a nod to one of his ready-mades, serving as a reference to the first he ever made, Bottlerack.

The bottle brush also casts a shadow, taking the shadow count up to four, when displayed properly that is. Sadly, in some showcases of Tu m’ this depth got lost. The original gallery might not have had overhead lighting and in a professional photo of the piece from 1941 there was an overhead lighting fixture it just wasn’t turned on. With proper lighting, the painted hand points to the bottle brush’s shadow on a canvas within a canvas in a bit of painting-ception. Without it, it’s just a hand pointing at a white rectangle.

The painted hand, being the kind of illusionism Duchamp wasn’t a fan of doing, was done by a professional sign painter he hired. This adds another layer of commentary, as the artist's ready-mades (themselves coy musings on post-war industrialization and consumerism) insist that the hand of the artist has nothing to do with art, it is rather the choice to call something art that makes it so. It's also a humble reminder that painting is not just an art form, but also a profession.

And yet there’s even more to unpack, not the least of which is the literal rip in the canvas, literally challenging the viewer to see through the piece itself. It’s safe to say the color swatches had meaning to the intellectual Duchamp as well. One of Duchamp’s contemporaries, Kazimir Malevich, was working with showcasing the "purity of color" in his paintings. Duchamp disagreed with this, as he saw paints not as a pure representation of one color, but as a product mass-produced and developed by many hands before being applied to a canvas. He saw casting one color over a canvas and labeling it as “pure” as another illusion, or delusion, in itself.

Lastly, there’s the title, Tu m’. The title is French, an informal “you” followed by “me” with the following verb missing. In Duchamp’s words: “The title made no sense. You can add whatever verb you want as long as it begins with a vowel”. Critics often read it to be tu m’ennuies (you bore me) or tu m’emmerdes (you annoy me), but any title that’s grammatically accurate is technically correct.

Sources

- Baas, Jacquelynn. Marcel Duchamp and the Art of Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019.

- Barbour, Susan. "Duchamp's Long Shadow: The Secret Meaning of "Tu M'"." Los Angeles Review of Books. April 10, 2017. Accessed March 26, 2021.https://lareviewofbooks.org/ article/duchamps-long-shadow-the-secret-meaning-of-tu-m/.

- Joselit, David. Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp, 1910-1941. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2001.

- Kuenzli, Rudolf, and Francis M. Naumann. Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996.

- Ramírez, Juan Antonio. Duchamp: Love and Death, Even. London: Reaktion Books, 1998.

- "Tu m'." Yale University Art Gallery. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://artgallery.yale.edu/ collections/objects/50128.