More about Kazimir Malevich

- All

- Info

- Shop

Works by Kazimir Malevich

Contributor

Kazimir means something like “showing the world," so of course he became a painter.

Father Malevich was manager of a sugar factory. Kazimir spent his childhood on sugar-beet plantations together with his 14 siblings (of which only 9 survived). His farming childhood would later on inspire him to paint his “peasant series”. The Malevich family lived far from any cultural centers, and far from anything else for that matter. Kazimir knew nothing about painting or art in general, but he was super impressed by the beauty of the surrounding landscapes. He called these memories “negatives that needed to be developed”, very poetic.

One day young Kazimir saw a man painting a roof, which “was turning green like trees and the sky." What? Anyway, after the guy finished and left, little rascal Kazimir sneaked onto the roof and started painting. This wasn’t necessarily a big success, but he fell in love with it. His parents bought him his first brush at the local pharmacy. It was a brush which other people used to anoint the throat of diphtheria patients…which is disgusting. Kazimir absolutely loved his brush though, much better than a pencil. He loved that the brush allowed him to cover larger surfaces, something which would eventually become his trademark. Some time after they bought him his brush, his parents also bought him a set of paints. This was a turning point though in Kazimirs' life, but at the time no one realized. No one cared, either. I mean he was supposed to follow in his dad’s footsteps and choose a profession worthy of a “real man." Painters aren’t real men!

Like any teen, afraid to disappoint their parents, Kazimir went to agricultural school. He hated it, but it was the only diploma he would ever earn. At the age of 18 Kazimir and his family moved to Kursk in southern Russia. That’s where Kazimir married a girl called Kazimira and fathered two children. I was so hoping one of them was called Kazimini, but nope, Anatoly and Galina. Even though Kazimir and Kazimira sounded awesome together, their marriage didn’t last. Kazimir couldn’t afford to fully dedicate himself to painting, so he worked as a drawer at the Kursk-Moscow railway. He eventually moved to Moscow and tried to enter the Moscow School of Arts and failed. He tried again and again, but kept failing. He was forced to move back to Kursk and this was also when he and Kazimira decided to file for divorce.

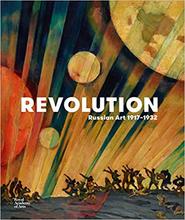

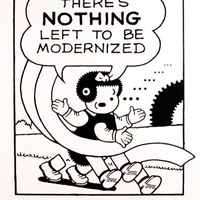

Later on Kazimir took part in the “Jack of Diamonds” exhibition, which brought together some cool and radical avant garde painters. From then on Kazimir exhibited at basically any “scandalous” exhibition. Because yeah, his work was considered pretty scandalous, probably because it wasn’t realistic but “cubo-futuristic”. While living in st Petersburg Kazimir tried to be even more provocative and entered the “Union of Youth”, a group of avant garde painters and futurist-poetry weirdos. The group created the first ever futurist theater, it was meant to be super provocative, and yeah it was! All those basic bitches were outraged, they started shouting and the whole thing turned out to be a huge scandal!

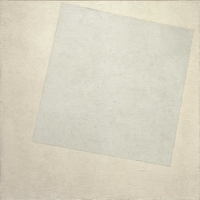

When Stalin got in charge, he changed the focus of art allowed in Russia. From now on, only paintings with educational value could be shown. Every single painting that wasn’t considered “educational," was packed into trains and shipped off to Siberia. Kazimir's work was described by Stalin as “bourgeois” and confiscated as well. In relation to this, he was arrested twice, but released each time. In 1930 he was arrested by the United State Political Agency. He was held for questioning on a charge of espionage because he visited Poland and Germany in 1927. Kazimir was released after six months and given 3 choices: 1. He could leave the country; 2. He could close himself in a room and work just by himself; or 3. He could become a realist painter. He chose the third option and tried to be a realist painter for a while. But, while in prison, Kazimir developed cancer and died 5 years later. On his deathbed, a black square painting was exhibited above him. Take that, Stalin!

In 2002 a black square painting sold for $1 million by Vladimir Potanin and donated to the State Hermitage Museum collection. This donation was the largest donation in Russia since Lenin forced nationalization in 1918. A few years later in 2008, the painting Suprematist Composition sold for a whopping $60 million, a world record for any Russian work of art ever sold.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Kazimir Malevich

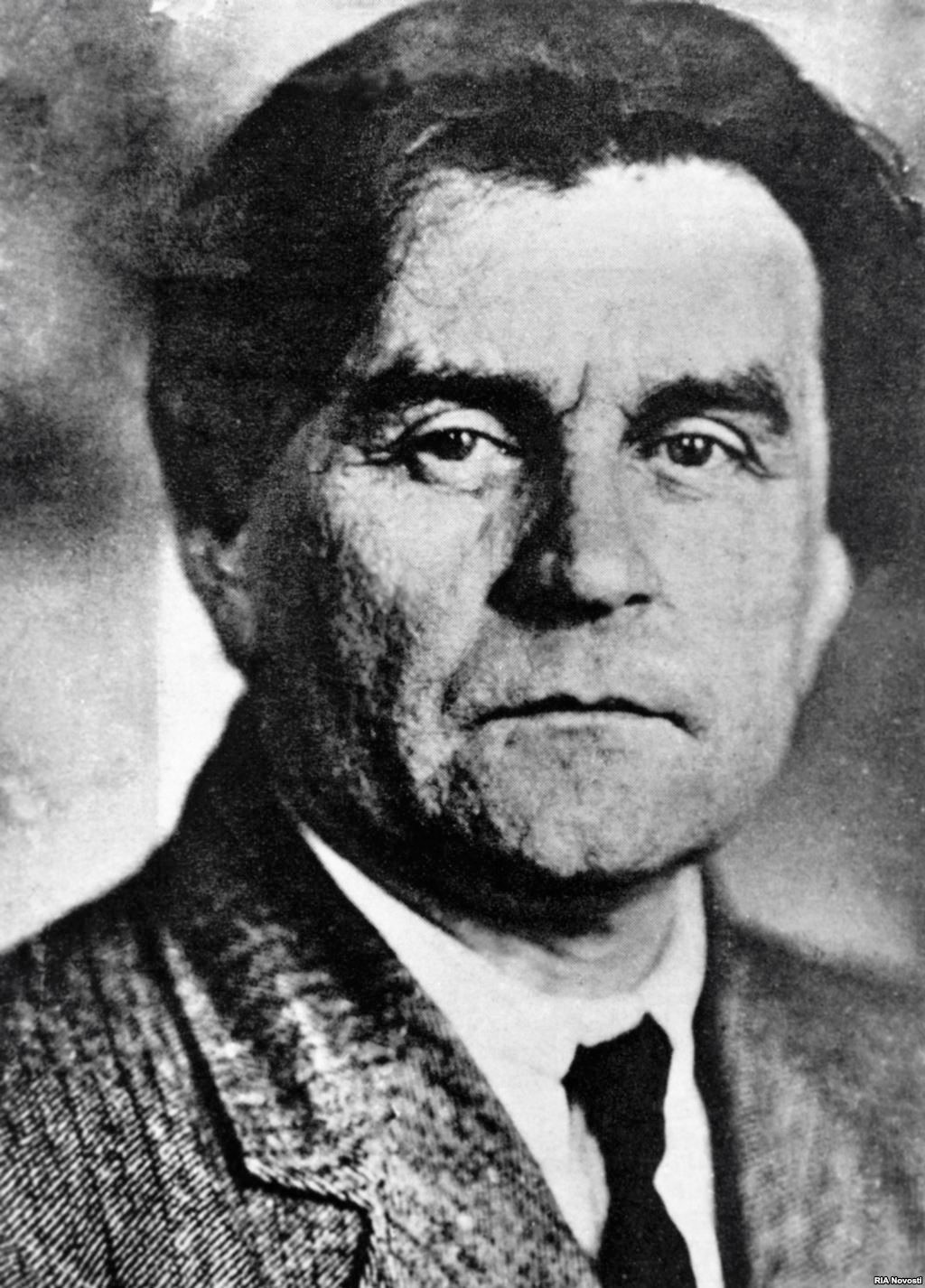

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (23 February [O.S. 11 February] 1879 – 15 May 1935) was a Russian avant-garde artist and art theorist, whose pioneering work and writing influenced the development of abstract art in the 20th century. His concept of Suprematism sought to develop a form of expression that moved as far as possible from the world of natural forms (objectivity) and subject matter in order to access "the supremacy of pure feeling" and spirituality. Born in Kiev, modern-day Ukraine, to an ethnic Polish family, Malevich was active primarily in Russia and became a leading artist of the Russian avant-garde. His work has been also associated with the Ukrainian avant-garde, and he is a central figure in the history of modern art in Central and Eastern Europe more broadly.

Early in his career, Malevich worked in multiple styles, assimilating Impressionism, Symbolism, Fauvism, and Cubism through reproductions and the works acquired by contemporary Russian collectors. In the early 1910s, he collaborated with other avant-garde Russian artists, including Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova. After World War I, Malevich gradually simplified his approach, producing key works of pure geometric forms on minimal grounds. His abstract painting Black Square (1915) marked the most radically non-representational painting yet exhibited and drew "an uncrossable line (…) between old art and new art". Malevich also articulated his theories in texts such as From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism (1915) and The Non-Objective World (1926).

His trajectory mirrored the upheavals around the October Revolution of 1917. In 1918, Malevich began teaching in Vitebsk along with Marc Chagall. In 1919, he founded the UNOVIS artists collective and had a solo show at the Sixteenth State Exhibition in Moscow in 1919. His reputation spread westward with solo exhibitions in Warsaw and Berlin in 1927. This marked the first and only time Malevich ever left Russia. From 1928 to 1930 he taught at the Kiev Art Institute alongside Alexander Bogomazov, Victor Palmov, and Vladimir Tatlin, while publishing in the Kharkiv magazine Nova Generatsiia (New Generation). Repression of the intelligentsia soon forced him back to Leningrad. By the early 1930s, Stalin's restrictive cultural policy and the subsequent imposition of Socialist Realism had prompted Malevich to return to figuration and to paint in a representational style. Diagnosed with cancer in 1933, he was not allowed to leave the Soviet Union to seek treatment abroad. While constrained by his progressing illness and Stalin's cultural policies, Malevich painted and exhibited his work until his death. He died from cancer on 15 May 1935, at age 56.

His art and his writings influenced Eastern and Central European contemporaries such as El Lissitzky, Lyubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko and Henryk Stażewski, as well as generations of later abstract artists, such as Ad Reinhardt and the Minimalists. He was celebrated posthumously in major exhibits at the Museum of Modern Art (1936), the Guggenheim Museum (1973), and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1989), which has a large collection of his work. In the 1990s, the ownership claims of museums to many Malevich works began to be disputed by his heirs.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Kazimir Malevich