More about The Art of Conversation

Sr. Contributor

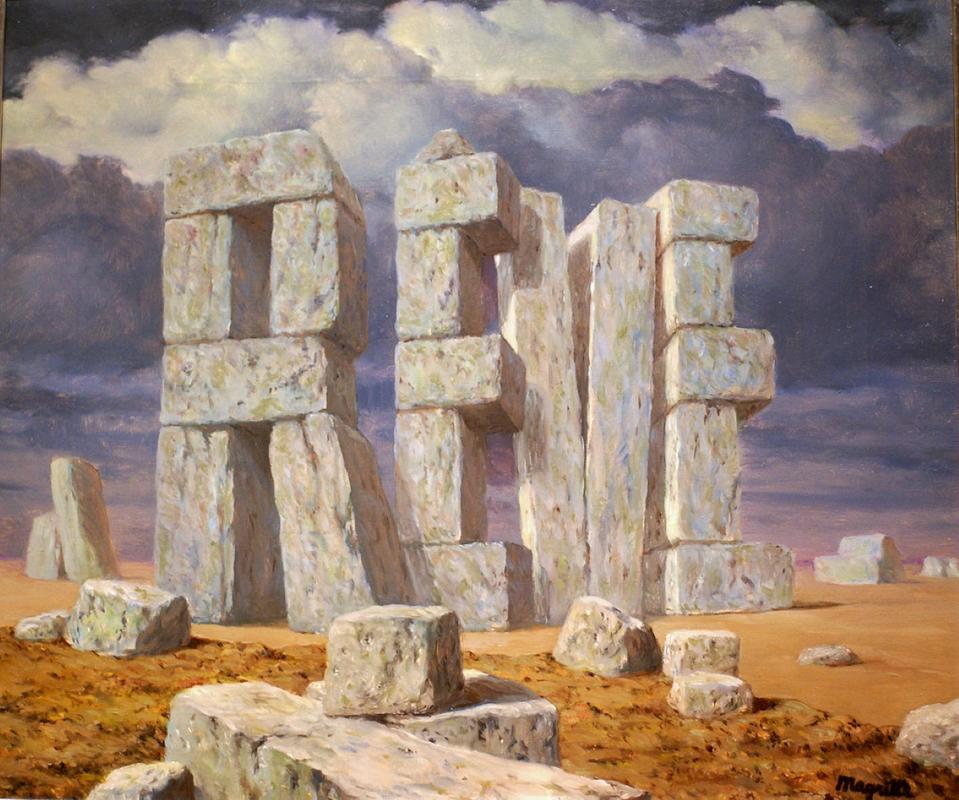

René Magritte confuses us with his words in The Art of Conversation.

Even people who are not familiar with the name of René Magritte will still recognize a lot of his paintings, as some of them have become a part of popular culture. Surrealistic paintings tend to do that; just take a look at Salvador Dali’s iconic The Persistence of Memory, where the melting clocks seem as familiar as Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night.

Combining words and images to create a work of art is something Magritte would do on more than a few occasions. One of his most well-known works, The Treachery of Images, was a challenge to the viewer, in a way that hadn’t been done quite like that before. Really, it’s not a pipe? L’Art de la Conversation (this version), painted almost 25 years later, was not quite as bold as Treachery. In fact, it looks pretty straightforward.

At first glance, it looks like Magritte has simply spelled out his first name “René,” using carved stones. This is what I initially thought, but a closer look shows that it actually says “Reve,” which means “dream” in French. So, this makes a bit more sense, when you see some of the other odd paintings Magritte has done. For example, check out Pleasure, where a young woman is biting into a living bird. Yikes!

Just to keep things confusing, Magritte painted at least four other works with the same title, including one version similar in style to ours and also done in 1950, one in 1963, and this one completed in 1962. Three of these (counting the one in this article), are done using stones piled on each other to spell out a word, while the others are completely different visual images.

This version of Conversation also seems to be the only one that does not have a pair of tiny figures wearing bowler hats in the scene. Magritte uses these figures in several of his paintings, standing in front of the giant blocks of stone, floating in the clouds, and standing near what look like giant chess pieces among the trees.

Magritte believed that the name of an object was not important, and this showed in his “word-images,” where he makes the point that what you see may not be what it is, as in “One mustn’t mistake a picture for an object that one can touch.” This point of view may be related to his time hanging out with the Dada artists, but Magritte himself is not usually considered part of that movement. Opinions vary widely on that point, however, as Surrealism and Dadaism began to flourish around the same time, after the first World War, and share many similarities.

When we put the “isms” aside, we’re left with Magritte’s clever way of combining words and images that motivate (or should motivate) the viewer to think about what they’re looking at. As a final example, there is his work The Empty Mask where, instead of images, he paints the words ciel (sky), corp humain (ou foret) (human body) (in the forest)), rideau (curtains), and façade de maison (house façade) within the painted frame, in order to let someone imagine what should be there. This has been called a “reverse rebus,” or a “verbal-visual suggestion.”

Sources

- Allmer, Patricia. René Magritte. London: Reaktion Books, 2019.

- Haskell, Caitlin, and Magritte René. Magritte: The Fifth Season. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2018.

- Kantrowitz, Jonathan. “MAGRITTE. The Treachery of Images.” MAGRITTE. THE TREACHERY OF IMAGES, January 1, 1970. http://arthistorynewsreport.blogspot.com/2017/03/magritte-treachery-of-….

- MATHEWS, TIM. "Figure/Text." Paragraph 6 (1985): 28-42.

- Paquet, Marcel. Rene Magritte 1898-1967. Taschen, 2000.

- Schmitz, Julia. “The Stumbling Blocks of Our Language.” SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT, February 22, 2017. https://www.schirn.de/en/magazine/context/magritte/rene_magritte_ferdin….