More about Talcott Williams

- All

- Info

- Shop

Editor

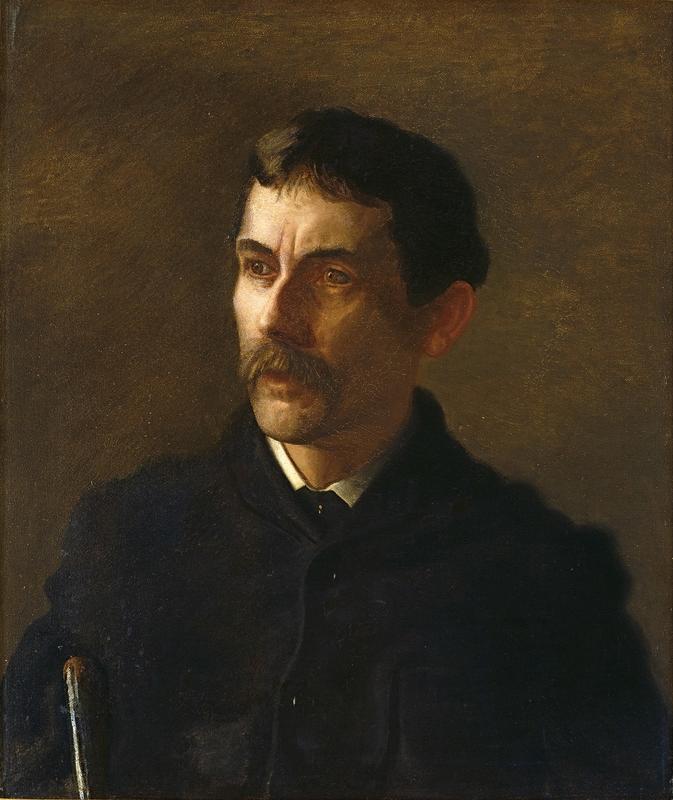

Talcott Williams was charming and gregarious, but quite possibly a frustrating person for Thomas Eakins to paint.

Williams was born in 1849 in Abeiz, Turkey, to a pair of congregational missionaries. Though he returned to the United States to round out his education and study at Amherst College, his remarkable upbringing gave him broad knowledge of Eastern languages and culture that would come in handy for him when he embarked on a career in journalism in the 1870s. He ended up an Associate Editor of the Philadelphia Press, where his penetrating editorials earned him a reputation as the most respected culture critic in the city, and he was later promoted to Managing Editor, a post he held for 32 years.

An important figure in Philadelphia’s intellectual circles, Williams was friends with the likes of Cecilia Beaux, Shakespeare scholar Horace Howard Furness, eminent surgeon D. Hayes Agnew, and even Walt Whitman. He promoted the work of young artists, was interested in early photography experiments, and covered the pioneering work of Eadweard Muybridge. Williams also wrote books, supported archeology projects, kept an extensive collection of newspaper clippings, and donated materials to the Smithsonian Institution. In 1912, he was appointed the director of the Columbia School of Journalism. The tireless Williams represented a new type of journalist: well-connected, intellectually curious, and supremely well-informed. As Walt Whitman said of Williams, “The only thing that saves the Press from entire damnation is the presence of Talcott Williams. Now, there’s a man with some stuff to him.”

Williams met the Realist painter Thomas Eakins sometime in 1881, probably at the Pennsylvania Academy, where Eakins was teaching at the time. Williams would just go there and introduce himself to people, an unfathomable act to introverts everywhere but one that seems in keeping with his charisma and curiosity. Williams and Eakins quickly struck up a friendship. Eakins was reportedly quite fascinated by Williams’ face, which was very animated, often bubbling over with enthusiasm about any given topic, and was characterized by a magnificent walrus mustache and bushy eyebrows.

Eakins even included a portrait of Williams in his famous 1885 painting, The Swimming Hole. It depicts a group of men cavorting about a lakeshore in the buff. Williams is the figure on the far left lounging on the rock. (You can tell him by his hairline and enormous mustache.) The figure swimming on the far right is a self-portrait of Eakins. Between them is a group of student artists. Some have suggested that Williams’ and Eakins’ position as bracketing figures is meant to suggest the prominent role the two of them played in helping the young artists get their start. However, Williams likely never actually went to Dove Lake, where the painting was set. He probably modeled for Eakins in his studio instead.

This particular portrait was painted in 1889. In October of that same year, Williams wrote to his sister about sitting for Eakins. He said Eakins didn’t charge his typical $500 fee for the portrait, as he should have, but instead was doing it out of love. He went on to say that, in order to demonstrate his appreciation to Eakins, he tried to “be as entertaining as [he] knew how” during the sitting. One has to imagine that this means he talked the entire time. It’s not much of a stretch, given that his nickname was “Talk-a-lot” Williams, and the fact that Eakins painted him with his mouth open and a look of focus on his face, both of which seem to suggest a certain chattiness. (Eakins also made a cast of his face, so maybe then Williams actually had to simmer down and be quiet.)

The bust-length portrait is typical of Eakins during this period. Starting around 1887, he transitioned from painting brightly lit portraits to painting figures in isolation, often in dark, muddy-colored settings. His portraits lack the glamour of those by his contemporaries like Cecilia Beaux, James McNeill Whistler, and John Singer Sargent, but they are incisive and frank. Their sitters appear to be thoughtful individuals, and many of them were exactly that–leading thinkers of Philadelphia at the time. Williams loved this portrait so much that he carried it around with him wherever he traveled on newspaper assignments. It made its way to places like Beirut, Paris, and London, becoming exceptionally well-traveled for a painting by Eakins.

Eakins also made a portrait of Williams’ wife, but it did not get the same honor. It remained unfinished, possibly due to an incident between Eakins and Mrs. Williams. As the story goes, she was posing for a full-length portrait similar to The Concert Singer one day when a friend of Eakins stopped by the studio, during which time she “tucked in her belly and stood like a stuffed manikin.” When the friend left, Eakins reportedly poked her in the tummy and said she could stop sucking it in and relax now. Rude. Needless to say, she was not pleased, and she refused to sit for him again. While Williams absolutely loved the portrait of her, Eakins refused to let him have it. It can now be seen at the Philadelphia Museum of Art under the title The Black Fan.

Sources

- Bolger, Doreen and Sarah Cash, editors. Thomas Eakins and the Swimming Picture. Lunenberg, VT: The Stinehour Press, 1996.

- Carr, Carolyn Kinder. “A Friendship and a Photograph: Sophia Williams, Talcott Williams, and Walt Whitman.” The American Art Journal 21, no. 1 (1989): 2-12.

- Kirkpatrick, Sidney D. The Revenge of Thomas Eakins. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “Thomas Eakins (1844–1916): Painting.” Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/eapa/hd_eapa.htm

- "Talcott Williams." National Portrait Gallery. Accessed February 15, 2022. https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.85.50