More about Soir Bleu

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

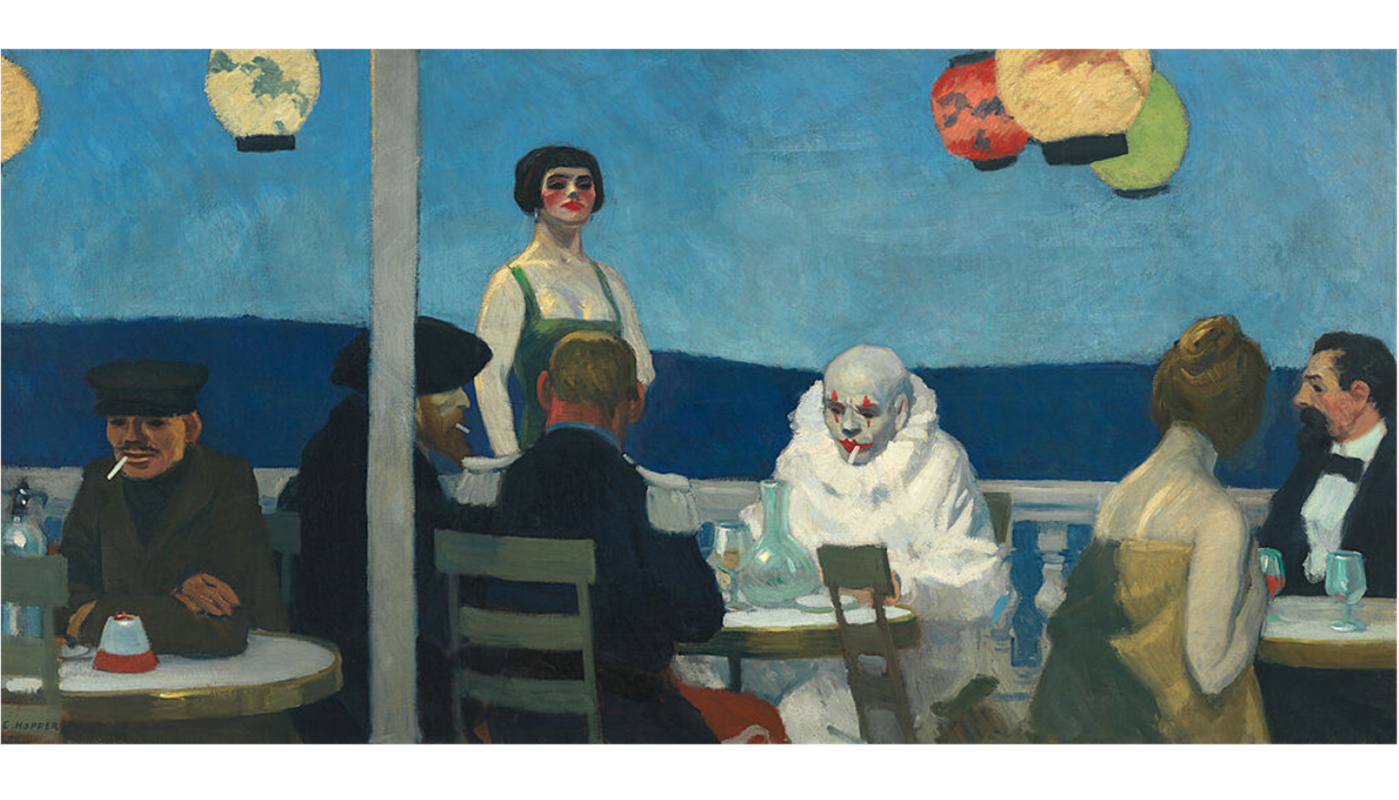

In Soir Bleu, Edward Hopper's angst regarding his career takes the shape of a sad clown smoking a cigarette.

Painted in 1914, four years after his last trip to Paris, Soir Bleu came about during a period of professional disillusionment for Hopper. He had been working a day job as an illustrator for 9 years and had yet to catch his big break. At the time, abstraction and cubism were all the rage, but young Hopper was committed to realism; Picasso was smack dab in the middle of synthetic cubism and Matisse was off painting technicolor, but Hopper was committed to painting stark, photographic landscapes with clearly defined context. This eventually worked out just fine for him, but in the middle of a flourishing abstract art market, it meant rice and beans— and paintings of sad, alcoholic clowns.

Set in a cafe similar to the kind Hopper probably frequented during his Parisian travels, the painting features several strangers, some coupled and some alone, each absorbed in their own thoughts and conversations. You’ve got a standing woman— likely a sex worker of some sort, given her powdered face and low-cut dress— a military man with some very fancy epaulettes, a bohemian dude with a nice fluffy beard, and then a couple of aristocrats chatting it up in the corner.

Then, at the visual center of the piece, you’ve got the aforementioned sad clown, smoking a cigarette and staring glumly down at the table. He’s wearing the classic outfit of Pierrot, a foolish, clown stock figure in commedia dell'arte, defined by a youthful naivete and a willingness to be vulnerable despite being continuously subjected to (humorous) physical and verbal abuse. Pierrot is often a sad little figure, perpetually optimistic and so constantly let down by the cruelty of his circumstances, a character Hopper may or may not have seen himself reflected in.

Though Soir Bleu is a figure painting, depicting a crowded cafe, the characters seem lonely. The ironic isolation one can feel despite living in a populous city would become a sort of trademark for Hopper when he moved back to New York - take, for instance, Room in New York or his iconic Nighthawks. As art historian Rick Brettell describes Soir Bleu, "Everybody is separated from everybody else. Hopper kind of translates it into an everyman setting, in which most of the people in it, are part of a kind of world of alienated urban entertainment, in which one is always searching for a meaning somewhere else, in a costume or in a prostitute or in a drink or in a cigarette or in a party."

Sources

- Brettell, Rick. “Edward Hopper, Soir Bleu, 1914.” Whitney Museum of American Art. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://whitney.org/media/945. Transcript of audio recording.

- Edward Hopper / Soir Bleu / (1914). (2014). The AMICA Library. http://www.davidrumsey.com/amica/amico5106321-124554.html

- Ritter, Naomi. Comparative Literature Studies, vol. 16, no. 4, 1979, pp. 355–57, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40468090. Accessed 22 Apr. 2022.

- Samels, Z. (2016). Artist Info. National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1404.html

- Welby-Everard, Miranda. “Imaging the Actor: The Theatre of Claude Cahun.” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 29, no. 1, 2006, pp. 1–24, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600491. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.