More about Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

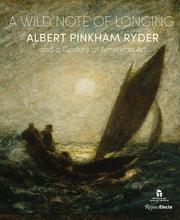

By Albert Ryder’s own account, he was so inspired when he began painting Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens that he worked on it for 48 hours straight, unable to put his brush down even for food or sleep.

Immediately after rushing home from Richard Wagner’s opera Die Götterdämmerung (or, in English, “The Twilight of the Gods”), the last in Wagner’s 12-hour-long, Game of Thrones-esque "Ring Cycle," Ryder dropped everything to get straight to work on this expressive and moodily-lit interpretation of the opening scene of the third act. The man on horseback is the legendary Norse hero Siegfried, who has just gotten separated from his hunting party while tracking a bear. The three Rhine maidens bathing in the river below are asking him to return a magical golden ring that was stolen from them by a dwarf named Alberich, which Siegfried recently acquired by slaying a dragon with his magic sword. Siegfried considers granting their request until they warn him that whoever possesses the ring is cursed to die a violent death; feeling threatened, he rides off with the ring...only to be violently murdered shortly thereafter, just as the Rhine maidens prophesied.

Ryder was far from alone in his enthusiasm for Wagnerian opera; in the 1880s, it was regarded with near-religious reverence by many audience members at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. One observer described feeling a crackling like that of “magnetic shocks” throughout the emotionally overwrought audience, whipped up to a frenzy by music which was intended to stir: “One could hardly listen to the Götterdämmerung among the throngs of young enthusiasts without paroxysms of nervous excitement,” concluded his account. Although it may be hard to imagine a 12-hour-long opera having such a devoted fandom today, Wagner’s operas bore many strong similarities to popular contemporary TV dramas, films, and video games, including the use of leitmotifs—short musical themes that are used to represent recurring characters, objects, and ideas in a story. Although he didn’t coin the term, Wagner is the most famous early example of a composer using leitmotifs in his music, and is commonly cited as being responsible for their present-day ubiquity in musical storytelling. Another notable use of leitmotifs is in the scoring of the "Lord of the Rings" films, which of course feature a very similar ring of power to the one found in Wagner’s "Ring Cycle." In fact, many elements of Wagner’s Norse-mythology-inspired epic have become staples of the fantasy genre today: dragons, elves, giants, gods, and helmets which provide their wearer with a cloak of invisibility (sound familiar?) all feature at some point in its sprawling story.

Ryder, caught up in a mood of “nervous excitement” like so many viewers of Götterdämmerung before him (and I get it—a good fantasy story makes me feel exactly the same way), began working feverishly on his painting immediately upon returning home from the opera, so as to capture the emotionality and drama of the music while it was still fresh in his mind. The expressive curves of landscape and trees coupled with the eerie lighting of the scene echo the ominous mood of the music—only Ryder translated the emotion of the sounds of the opera into an emotion of line and light. In this way, we can think of Ryder (as well as contemporaries like Odilon Redon) as a precursor to the Abstract Expressionist movement; Ryder similarly sought to render subjective, emotional experience visible through form. His work was hugely influential on the art of Jackson Pollock (as we can clearly see in Pollock’s 1935 painting Going West; the swirling clouds and creepy moonlight are nearly identical), and we could draw parallels with Wassily Kandinsky as well, since both he and Ryder were interested in making music visible through their use of color and line.

Ryder was absolutely obsessed with capturing the perfect light in his work, a pursuit which led him to make use of unconventional materials in his paintings, like candle wax, cooking oils, and varnish. He would painstakingly layer paint and these other materials onto his canvases over the course of decades, resulting in a thick slab of pigment which has, unfortunately, been highly susceptible to decay over the years—hence the cracks visible in the paint of Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens. Many of his paintings have ended up in far worse condition than this one, some darkening so much that it’s difficult to discern what they’re depicting; others, never fully dried (despite being over a century old), are gooey to the touch; and still others have begun to slide off their canvases entirely. But the otherworldly lighting he achieved with his unorthodox materials nonetheless feels perfectly suited to the fantastical subject matter of the Ring Cycle.

Discussing his own artistic personality, Ryder once wrote, “Have you ever seen an inchworm crawl up a leaf or a twig, and then clinging to the very end, revolving in the air, feeling for something to reach something? That’s like me. I’m trying to find something out there beyond the place on which I have footing.” In this work, that reaching for another world beyond our own is palpable, not just in the painting’s subject matter, but also in the lighting that looks like it could have been taken straight from a dream. It’s a tragedy that Ryder’s paintings are slowly fading into obscurity, but at least we can still go to see them in all their cracked and gooey glory today.

Sources

- “Albert Pinkham Ryder.” The Art Story. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/ryder-albert-pinkham/.

- “Albert Pinkham Ryder Artworks.” The Art Story. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/ryder-albert-pinkham/artworks/.

- Burchard, Hank. “Albert Ryder’s Gooey Grandeur.” The Washington Post, April 6, 1990. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/04/06/albert-ryde…- grandeur/fb26ae98-1877-4508-aba6-3818869b6c76/.

- Homer, William Innes. “Albert Pinkham Ryder.” Art Journal 50, no. 1 (1991): 86-89.

- “Jackson Pollock Artworks.” The Art Story. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/pollock-jackson/artworks/.

- Johnson, Diane Chalmers. “‘Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens’: Albert Pinkham Ryder’s Response to Richard Wagner’s ‘Götterdämmerung.’” American Art 8, no. 1 (1994): 22-31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3109160.

- The Musicologist. “Understanding the Leitmotif.” YouTube video, 9:08. June 16, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bR2EobBG9wQ&ab_channel=TheMusicologist.

- Rightside, Bob. “The Influence of Wagner’s Ring on the work of J.K. Rowling.” Medium, August 12, 2019. https://medium.com/@bob.rightside/the-influence-of-wagners-ring-on- the-work-of-j-k-rowling-d897a8e20b5b.

- Ross, Alex. “The Ring and the Rings.” The New Yorker, December 14, 2003. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/12/22/the-ring-and-the-rings.

- “Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens, 1888/1891.” National Gallery of Art. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.32624.html.

- Torchia, Robert Wilson. American Paintings of the Nineteenth Century: Part II. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/ publications/pdfs/American%20Paintings%20of%20the%20Nineteenth%20Century %20Part%20II.pdf.