More about Roadside Stand, Vicinity Birmingham, Alabama

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

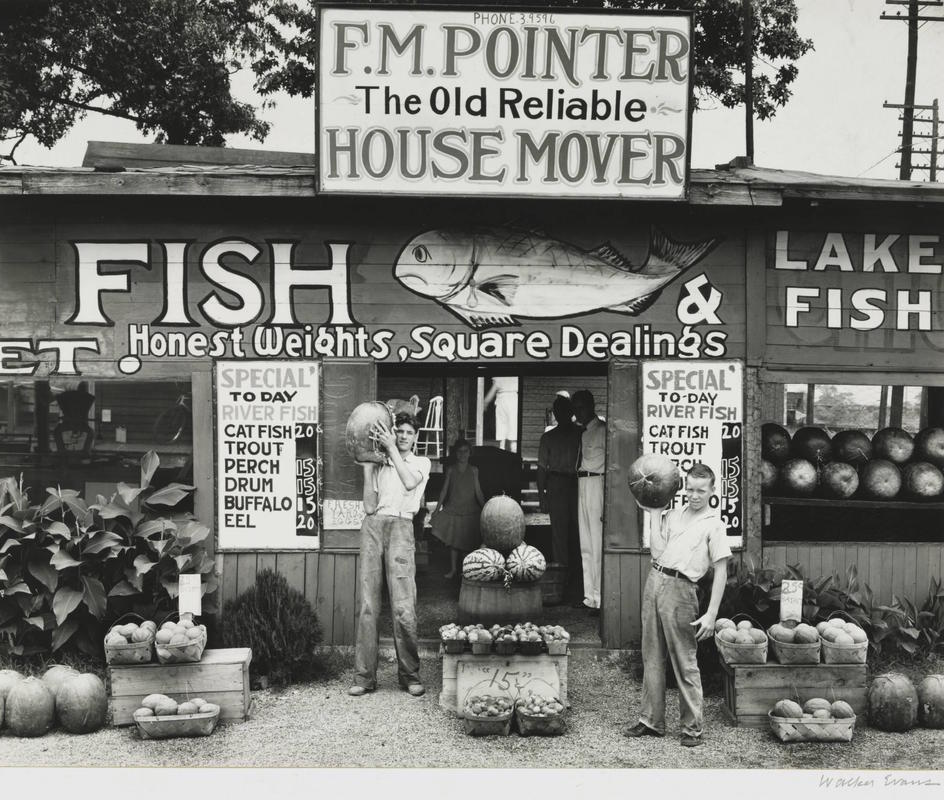

Roadside Stand, Vicinity Birmingham, Alabama is one of Walker Evans’s iconic images of Depression era Americans.

With looks of candid befuddlement and the awkwardness of a naively staged show, these people become the players in Evans’s pictorial performance of the Depression.

Evans played paparazzi for the United States government, or Farm Security Administration, in the name of historical documentation and ultimately produced nearly 80,000 photographs of the Depression-era life. In 1936, he took his show on the road when he traveled to Hale County, Alabama with his friend, writer James Agee. Together they stayed with three impoverished, white tenant farming families and documented their experiences through image and text, ultimately leading to the publication of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men in 1941.

This family is an apt example of the farming families that Agee and Evans stayed and worked with while on their Fortune magazine experiment. Their purpose was to “concentrate ordinariness until it becomes sublime," taking picture upon picture to allow the subjects to shine. However, despite how honorable this sounds, Agee and Evans desired purely to describe the life and situation of the tenant farmers in Alabama with as much accuracy as possible, with no intention of trying to actually solve the economic problems ravaging the area.

Embedded in this powerful photo essay, filled with images and words of poverty and need, you find Roadside Stand, Vicinity Birmingham, Alabama. With all its inherent naïveté, this semi-comic family portrait displays honest, unadulterated American pride in consumerism, no need for neon signs. The family, boasting their many watermelons, long lists of fresh fish, and baskets bursting with various produce, gaze unabashedly at the camera, seemingly showing off their produce and themselves. The familiarity implied through Walker Evans’s camera lens reflects a longing for this perfectly imperfect era of traditional, rustic Americana.

Evans believed photography to be “the capture and projection of the delights of seeing; it is the defining of observation full and felt.” Through his all-seeing lens and his detailed focus on pride and plenty, the narrative of this little roadside stand remains unaffected by the corruption of money and technology, firmly protected from the changes of time. Evans made this family’s 15-minutes of fame never ending, cementing their importance as the era’s wishful vision of the iconic American farming family.

Sources

- “Roadside Stand Near Birmingham, Alabama.” 20x200, Accessed July 30, 2018. https://20x200.com/products/roadside-stand-near-birmingham-alabama

- “Roadside Stand Near Birmingham, Alabama.” Artsy, Accessed August 4, 2018. https://www.artsy.net/artwork/walker-evans-roadside-stand-near-birmingh…

- “Roadside Stand, vicinity Birmingham, Alabama.” Google Arts & Culture, Accessed August 3, 2018. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/roadside-stand-vicinity-birming…

- “Roadside Stand, Vicinity Birmingham, Alabama.” The Cleveland Museum of Art, Accessed August 10, 2018. http://www.clevelandart.org/art/1975.36.

- Baier, Leslie. “Visions of Fascination and Despair: Relationship between Walker Evans and Robert Frank.” Art Journal, Vol. 41, No. 1, Photography and the Scholar/Critic (Spring 1981): 55-63.

- Austgen, Suzanne A. “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Agee and Evans’ Great Experiment” https://history.hanover.edu/hhr/hhr93_5.html