More about Reclining Woman

Contributor

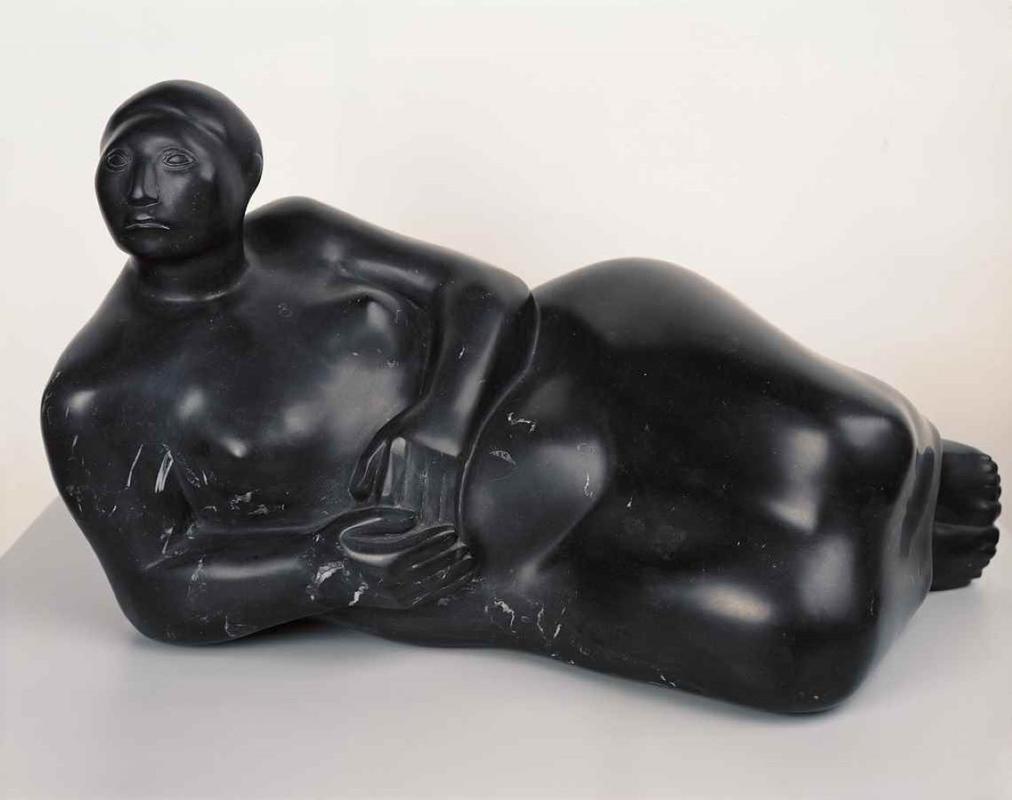

His name may not yet be "as big" as Picasso, but Zúniga's masterful Reclining Woman, la Mujer Reclinada, gives a faithful portrayal of the same lifelike body shape that appears in Picasso.

She's not interested in adhering to the form of the artist or atelier—the artist seeks her out, turning the power dynamic on its head. When Zúñiga released Mujer Reclinada in 1955, indigeneity and indigence were supposed to be the same thing, in the eyes of the political establishment of both his adopted México and his native Costa Rica. The "beauty ideal" of the woman who stays indoors all day served the political goals of certain interests, selling skin-lightening cream, corsets, and so on. On the contrary, esta mujer prays for everything she needs for herself and her family, like her ancestors. It ain't no "Yellow Wallpaper" for her.

The critics call Zúñiga's work indigenismo, a perspective which apparently represents or relates to the people who you have to get out of the way, or bribe, in order to mine and destroy the earth for oil and other natural resources. According to one digital archive site, Zúñiga's models' "monumental bodies with markedly indigenous features refer to Pre-Columbian concepts of an earth mother" and put his work in conversation with indigenismo.

Just before he released Mujer Reclinada, Zúñiga received popular acclaim for sculptural installations at la Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes, a government agency in México City. Zúñiga produced this work around his twentieth year teaching at La Esmeralda school of painting, sculpture and printmaking, also in México City. When Zúñiga first got the job, he'd only been in México for two years, studying at the school. Around his fifth year wearing professorial corduroy-elbowed jackets, the Secretary of Public Education gave La Esmeralda a thumbs-up from the government, which made the school officially accredited. During that time, both Kahlo and Rivera also taught at the school.

Thirty-five years after he finished this work, Zúñiga lost his sense of sight, but he kept massaging the terracotta, producing new work for three more years.

Sources

- "Francisco Zúñiga." LatinArt.com, http://www.latinart.com/faview.cfm?id=81.

- "Francisco Zúñiga: La fuerza de la mujer indígena." Trianarts, Aug. 9, 2019, https://trianarts.com/francisco-zuniga-la-fuerza-de-la-mujer-indigena/#….

- Francisco Zúñiga en el Sector Comunicaciones y Transportes. Ciudad Universitaria Toluca, México: Centro de Investigación en Ciencias Económicas, 1994.

- "Mujer reclinada, 1955." MALBA, https://coleccion.malba.org.ar/mujer-reclinada/.