More about Picasso's Studio

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

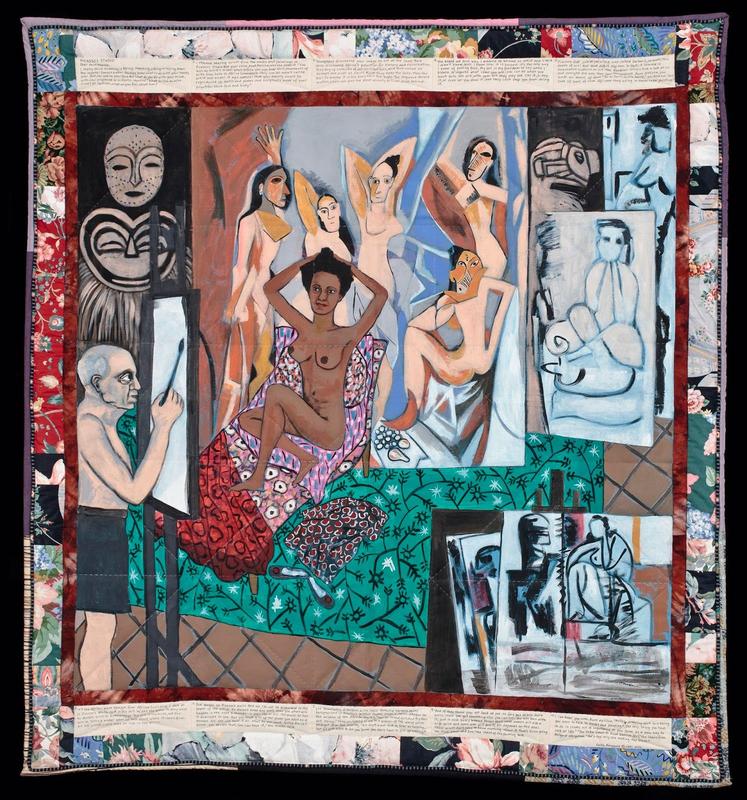

We don’t actually know what went on in Pablo Picasso’s studio, but in this story quilt, Faith Ringgold gave it her best guess.

And at first glance, it’s not exactly a flattering depiction. Picasso is delegated to a small, cramped corner of the quilt, whereas his subject sprawls on a couch, claiming space literally and figuratively. She looks elegant, refined, and at ease. He looks unshaven, old, and more than a little scrubby, which probably isn’t an accident. Ringgold’s quilts often mess with pre-existing narratives and re-imagine events from an alternate viewpoint.

When Ringgold created this quilt, she was likely frustrated with all the hoity-toity reverence given to Picasso, despite what she (and many others) saw as a misuse of black, African bodies. (Some other folks have posed the counter argument that he was commenting on the racism of the colonial West rather than participating in it, but that’s a story for another article). The famous cubist painting depicted, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, has been celebrated as a seminal work that had “immense consequences” on the art world writ large, shattering pre-existing expectations of realism and launching art into a new age of non-realistic interpretation. But Picasso’s “originality” was not entirely his own. Instead, he was drawing on a legacy of African expression, reusing it for his own purposes.

Ringgold’s quilt changes the narrative of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon from a work of Picasso’s individual genius to a work that looks to African imagery for its originality. Around the edges of the quilt, she prints the story of Willia, a fictitious African-American ex-pat, artist, and model living in 1920’s Paris, quite literally re-framing the story of Picasso’s genius to center a Black narrative. In Ringgold’s telling, Willia is writing to her Aunt about Picasso’s abuse of African imagery for his own artistic ends. Near the end of the text, she says “The European artists took a look at us and changed the way they saw themselves...It’s the African mask straight from African faces that I look at in Picasso’s studio and in his art. He has the power to deny what he doesn’t want to acknowledge. But art is the truth, not the artist. Doesn’t matter what he says about where it comes from. We see where, every time we look in the mirror.”

In an example of the appropriation Willia describes, despite the fact that all of the figures in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon are given white or white-ish skin, Picasso painted the two figures on the right with sharp, cubist features, reminiscent of African masks— like those Willia references and Ringgold has hanging up behind her. Even worse, when speaking of the choice, Picasso said that he wanted to "liberate an utterly original artistic style of compelling, even savage force.” Which is an okay-ish way to talk about painting, but was— and is— kind of a terrible way to talk about the bodies of your fellow humans, the idea of "savage" people being all too common in European discourse regarding Africa.

Additionally, the original painting famously depicts a brothel in Spain, a fact Ringgold almost certainly knew. Which could mean a couple things for this painting’s title: Ringgold is implying that Picasso depicted models as prostitutes, even though that’s not what they were. Or, Ringgold is implying that Picasso’s studio itself is a brothel. Either way, it’s a sick burn, one that takes a strike at the conventional narrative of Picasso’s greatness.

Sources

- Kramer, Hilton. "The Triumph of Modernism: The Art World, 1985–2005, 2006". Reflections on Matisse. 163.

- Leighten, Patricia. “The White Peril and L'Art Nègre: Picasso, Primitivism, and Anticolonialism.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 72, no. 4, 1990, pp. 609–630. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3045764. Accessed 15 June 2021.

- Ringgold, F. (1992). The French collection, La Collection Franc̦aise. B MOW Press.

- Race-ing Art History: Critical Readings in Race and Art History. United States, Taylor & Francis, 2013.