More about Oval Form with Strings and Color

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

A balanced breakfast for Barbara Hepworth includes one very large egg.

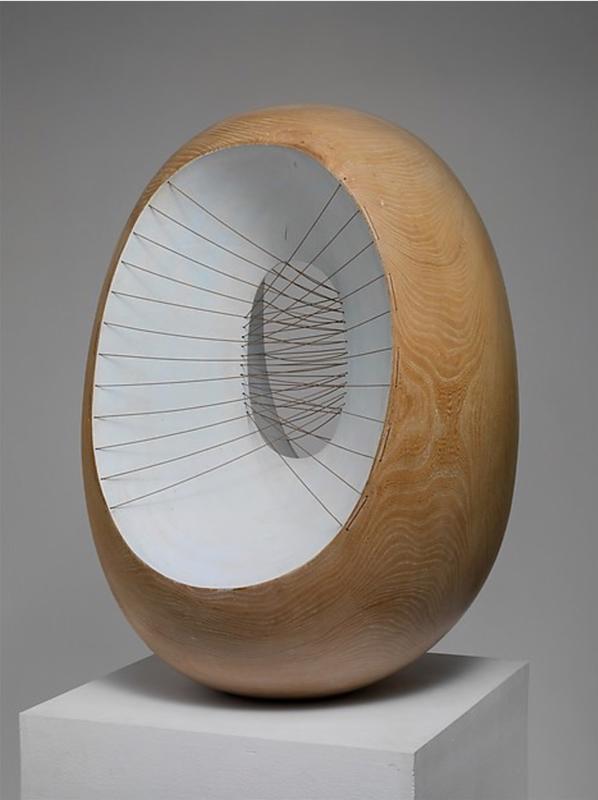

As far as names go, you can’t get more straightforward than Oval Form with Strings and Color. Barbara Hepworth may have chosen the most boring name possible for this seemingly simple piece, but trust me, it’s a lot more interesting than it sounds.

For one, it has a bronze twin painted green instead of white, but it’s not titled Oval Form No.2 or anything like that. It’s titled Spring,1966, a name that makes you think of nature and allergies. These twins probably hate being mistaken for the other, but their oval shapes suggest similar ideas of birth.

Starting in 1943, ovals replaced circles in Hepworth’s artwork. There aren’t many perfect circles in the natural world, so the oval represents a more organic structure, like an egg. While eggs are prone to break, it’s clear this egg is no Humpty Dumpty. The elmwood shell is bound by interweaving strings pulling toward the egg’s center. But what would happen if we cut the strings? The shell might remain intact, but the center would become empty and the sculpture would feel incomplete.

The strings might therefore represent children.The oval shape evokes images of eggs, ovaries, and the womb, all of which connect to motherhood and birth. Hepworth often defended her status as both mother and artist, claiming her domestic lifestyle never prevented her from working; if anything, raising children improved her productivity and marriage. Even with deep ties to motherhood, Hepworth never considered herself a “woman artist.” Her work isn’t feminine because it contrasts with masculinity; it’s feminine because it’s of her own experience.

Hepworth once said “As far as I'm concerned, in my work and in my life, the scales are in balance.” Oval Form is a great example of balance created by contrast. Natural wood/artificial string. Egg curves/linear string. Dependence/independence. Tension/stillness. With opposites unified together, Hepworth creates an unbreakable egg.

Hepworth started using ovals not long after visiting Constantin Brâncuși’s Paris studio in 1932. Constantin Brâncuși essentially pioneered modern sculpture; he prioritized the physical process of sculpting over the finished product, resulting in strange shapes made from unconventional material. If you ever find a statue that’s just a massive metal triangle, you can thank Brâncuși . Brâncuși became famous for his golden penis, which also features ovals, and after seeing his penis (the sculpture, of course) Hepworth began to favor the shape in her work. Bless friends and their phallic art.

Hepworth had lots of influential art buddies. Most notably was Henry Moore, known for his sculptures of blobby reclining women. The two were considered rivals among critics, even though they were close friends (and possibly lovers) through their career. It was Moore who introduced Hepworth to the idea of direct carving, a modern technique that focuses on a sculpture’s material instead of its meaning.

Hepworth also became close with Naum Gabo, a Russian artist famous for string sculptures that look like 3D versions of spirograph drawings. You know, the interlooping circle designs you made with protractors in math class? Gabo’s string sculptures inspired Hepworth to incorporate string into her own works to convey both fragility and balance in secure shapes.

On the other hand, it’s also likely that Hepworth just happened to have string lying around because she had a lot of cats- Nicholas, Mimi, and Tobey. Maybe it’s ludicrous to suggest that Hepworth’s sculptures are fancy cat toys… and maybe not. Hepworth’s former studios, now a museum, houses a cat that watches over the sculpture garden as though it was made just for her.

Sources

- Curtis, Penelope and Wilkinson, Alan G. Barbara Hepworth: A Perspective. London: Tate Gallery, 1994.

- Deepwell, Katy. 10 Decades: Careers of Ten Women Artists born 1897-1906. Norwich: Norwich Gallery, 1992.

- Neesmir, Cindy. Art Talk: Conversations with 15 Women Artists. New York: HarperCollins,1975.

- Hammacher, A.M. Barbara Hepworth. New York: Thames and Hudson, Inc., 1998

- Hepworth, Dame Barbara. Pictorial Autobiography. London: Tate Publishing, 1985.