More about "monument" for V. Tatlin

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

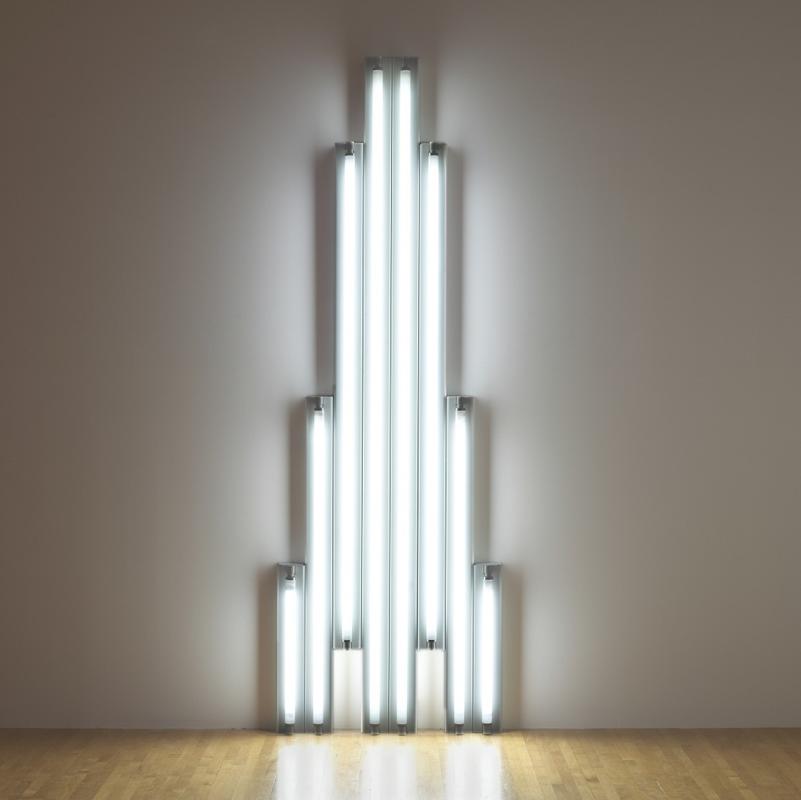

Dan Flavin’s “Monument” for V. Tatlin serves as a landmark of the minimalist movement.

Minimalism often gets written off as the movement for artists with no talent. Non-art lovers typically remark, “I could’ve done that,” when confronted with art like that of Donald Judd or Sol LeWitt, both of whom Flavin met while working at MoMA as an elevator operator, but to that I say, “Yeah, but you didn’t.” Flavin confronted this inferred laziness imposed by the general public upon minimalists, stating, “It’s important to me that I don’t get my hands dirty. . .It’s not because I’m instinctively lazy. It’s a declaration: art is thought.”

Minimal art doesn’t serve to showcase the sheer technical skill of the artist, but functions as a catalyst for the critical reconsideration of what defines art. At the conception of minimalism, the art world faced an existential crisis, much like I did when I learned about black holes. Perhaps Flavin’s fluorescent art “situations” acted as a light to prevent art from dissolving into a black hole itself. A black hole of infinite iterations of oil on canvas. Rather than categorizing art as either painting or a sculpture, minimalists began to define their works as “three dimensional objects.” Before you think to yourself, “Well, there isn’t really a difference between a 3-D object and a sculpture,” consider the following: is a light post a sculpture? Is it a three dimensional object? What about a metal grate? Or chicken wire? If you hang chicken wire on a wall, does that make it a painting? Minimalist artists aimed to push the boundaries of what may be considered art.

“Monument” for V. Tatlin references Vladimir Tatlin, the founder of constructivism, and his most famous work, Monument to the Third International, a design for a building that never came to fruition. He references Tatlin because he was “the first to free sculpture from representation and establish it as an autonomous form.” Flavin aimed to create an object that simultaneously separated itself from life and became an intrinsic part of it. His art consists solely of light, of fluorescent tubing that anyone could buy at Home Depot. As such, it emulates the most essential part of life. Perhaps the most intrinsic experience of life. Without the light of the sun and the light that we humans commercially produce, we could never exist. But Flavin’s works also detach themselves from the human experience by refusing to be representative art pieces. Unlike artworks that predate the pure abstraction that came about in the 20th Century, Flavin’s work declines to depict anything that we might find in nature, like a portrait, or a still life, or a landscape. Using only materials that anyone feasibly could buy and techniques that you don’t have to go to art school to learn, Flavin upheaved the art world’s definition of what can and cannot be considered art.

Sources

- "Dan Flavin." 56 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy. Accessed June 10, 2019. https://www.artsy.net/artist/dan-flavin.

- "Dan Flavin: A Retrospective." National Gallery of Art. 2019. Accessed June 10, 2019. https://www.nga.gov/features/slideshows/dan-flavin-a-retrospective.html….

- "Dan Flavin." Artnet. Accessed June 10, 2019. http://www.artnet.com/artists/dan-flavin/.

- Morris, Robert. "Notes on Sculpture 1-3." In Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas.