More about Katherine, Countess of Chesterfield, and Lucy, Countess of Huntingdon

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

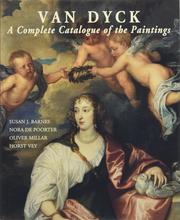

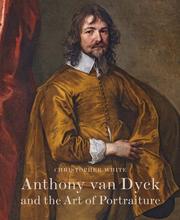

In Sir Anthony van Dyck’s dual portrait of Katherine, Countess of Chesterfield (left), and Lucy, Countess of Huntingdon (right), the baroque sumptuousness of their ultra-femme gowns, dazzling jewels, and porcelain-doll physiques belies two formidable matriarchs who lived gloriously on their own terms.

Who would guess that these blushing ladies of fashion rode the wave of power and sex in a turbulent century, surviving a machiavelian chess game of family drama that makes Succession look like The Waltons?

Intrigue ran in Katherine, Countess of Chesterfield’s blood. Her maternal grandfather, Sir Arthur Throckmorton, distinguished himself in the Earl of Essex’s Capture of Cadiz, but his sister Lady Bess incurred the wrath of Queen Elizabeth I by getting pregnant out of wedlock and secretly marrying the Queen’s favorite, Sir Walter Raleigh. As a young woman, Katherine was later wooed by (and said to be in love with) Bess and Walter’s son, Carew Raleigh. Katherine’s paternal grandfather, Edward Wotton, 1st Baron Wotton, eventually tried that same Sir Walter Raleigh for treason. Edward was a diplomat whose service to the Crown included interceding on Queen Elizabeth’s behest to persuade James VI and I to wed Anne of Denmark, and exposing Mary, Queen of Scots’ plot to assassinate Elizabeth to the French Court. He was also a closeted Catholic, a revelation which caused a scandal after his death.

Katherine took deftly to the family business, arming, financing, and plotting on behalf of King Charles I in the English Civil Wars, while shrewdly managing to secure her own estates from confiscation by the Parliamentarian forces (though she was briefly jailed for the effort). However, it was intrigue of a more domestic nature that claimed much of her attention. As governess to Charles’ eldest daughter Mary, Princess Royal, Katherine accompanied her charge to the Netherlands to wed future Prince William of Orange. In the Dutch Court, Katherine sparred with William’s mother, the Dowager Princess of Orange, for the upper hand over Mary’s interests. King Charles had entrusted Katherine with preventing consummation of the marriage until Mary was at least 14, as she was still pubescent, whereas William was already approaching his late teens. Unfortunately, Katherine failed spectacularly in her capacity as royal “cock-block,” learning after the fact that William had been sneaking into Mary’s bedchamber under her nose with the approval of Katherine’s adversary, the Dowager Princess.

Katherine knew a thing or two about nocturnal visitations, boasting a spate of husbands, admirers and lovers worthy of a bodice-ripping novel. Not least among these was the artist himself, Sir Anthony van Dyck. Their mutual acquaintance Lord Conway recorded the artist’s “gallantries for the love of that Lady.” It is unclear if Katherine requited this love, but muse and master are reputed to have been intimate. This could not have sat well with van Dyck’s mistress, the fiery courtesan Margaret Lemon, whom van Dyck’s colleague Wencelas Hollar called, “a dangerous woman,” and “demon of jealousy.” Margaret was so green-eyed over his unchaperoned sessions with female sitters that she threatened to bite off his thumb if she ever caught him in flagrante with one. Margaret need not have feared. Van Dyck’s relations with Katherine soured when they had a dispute over the price of a portrait, and he threatened to sell it to a higher bidder. He may also have been so besotted with Katherine he couldn’t bear to part with her image. In any case, they never mended the rift, so van Dyck most likely copied Katherine’s face in this painting from that earlier work.

From Katherine’s dizzying array of suitors, three were luckier enough than van Dyck to rise to the status of husband. Her first marriage, to Henry Stanhope, Lord Stanhope, left her a young widow with heavy debts and three children, feuding with her father-in-law over finances. Her second husband was Johan van der Kerckhove, Lord of Heenvliet, a Dutch diplomat she met in the retinue negotiating the marriage between Princess Mary and Prince William. Though their initial courtship turned contentious because Johan’s lower and foreign status would exclude potential children from inheriting Katherine’s assets, the marriage was ultimately successful, and Katherine commissioned a marble monument to honor Johan after his death. Husband number three was an old friend with whom she had once been accused of having an illicit affair, Daniel O’Neill, an Irish officer and Postmaster General to King Charles II. When Daniel died, Katherine inherited his office, making her the first female Postmaster General in British history, and leaving her a fabulously rich widow.

Katherine’s vast fortune at the end of her life also owes much to her own cutthroat business acumen. Not even her dearest kith and kin were spared her ruthlessness. For example, though she was as devoted to the Princess Mary as a surrogate mother, when the hapless princess died of smallpox at age 29 while still owing her a large sum of money, Katherine effectively stole Mary’s royal jewels and wardrobe, refusing to relinquish them until the debt was paid. Neither were her blood children above the fray. For half a decade, Katherine and her eldest son, Philip Stanhope, 2nd Earl of Chesterfield, engaged in a bitter inheritance dispute. Phillip sued his mother for access to funds allocated for his sisters. In retaliation, Katherine countersued Phillip, demanding all money he had received since his father’s death. The hostilities triggered a character assassination against Katherine, accusing her of contemplating switching allegiance to Oliver Cromwell (horror of horrors for a Royalist!).

Mother-son drama aside, by way of Phillip, Katherine may or may not be a 7th great-grandmother of Queen Elizabeth II. Her son’s second of three wives was Elizabeth Butler, who was, according to the memoirs of the Count de Gramont, a “very tempting and alluring” Irish brunette with enormous blue eyes and “a most exquisite shape.” Despite his wife’s obvious enchantments, Phillip was apparently otherwise entangled with King Charles II’s notorious chief mistress, Barbara Villiers. According to tell-all diarist Samuel Pepys and Gramont’s steamy memoirs, Elizabeth easily found two willing partners for revenge sex: her first cousin, Royal Navy man John Hamilton, and the Duke of York, future King James II. Despite his own liaison with Barbara, Phillip fumed with jealousy, sequestering his wife in Derbyshire where she gave birth to a daughter of doubtful paternity. This child, Elizabeth Lyon, Countess of Stanhope, went on to be a progenitor of the Queen, meaning that if Philllip was in fact the father, Katherine is a direct ancestor of the modern-day royal family. The mother met a more melancholy fate. Elizabeth Butler died at 25, allegedly poisoned by her vengeful husband. (Tune in next week, for another thrilling episode of Desperate Chesterfields!).

Lucy Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon’s origin story is no less soap-operatic. There was said to be “never so mad a lady” as Lucy’s mother, Eleanor Davies, and she was the sane one in her family. Eleanor’s brother/Lucy’s uncle, Mervyn Tuchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven, became the only member of parliament ever executed for a non-political crime after a trial so salacious it makes Depp v. Heard look like a paragon of good taste. Mervyn was accused not only of repeatedly sodomizing his male servants, but also enlisting them to rape both his wife, Lady Anne Stanley, and his son’s teenaged wife, Elizabeth Brydges, who was also his son’s stepsister and Mervyn’s own stepdaughter from Anne’s first marriage.

Witness Testimony alleged the following: Mervyn had debauched and groomed his male servants to be his lovers and accomplices. When his wife refused to sleep with other men for his sexual gratification, he held her down while a servant ravished her, then sodomized the servant as the traumatized Lady Anne attempted to stab herself. Mervyn further coerced his daughter-in-law/stepdaughter into laying with a servant multiple times while he watched, with the aim of inseminating her so he could disinherit his son. However, counter-testimony claimed Anne was willingly committing adultery with those same servants, and that they were all conspiring together with Mervyn’s son and daughter-in-law to eliminate him and usurp control of his estate. To this end, a page who was executed for committing sodomy with Mervyn called Anne, “the wickedest woman in the world.” Mervyn professed his innocence to the last, but was summarily beheaded on Tower Hill. Incidentally, if you think the current British royals are messed up, Anne was once considered next in line for the throne.

Conjugal strife was also brewing in Lucy’s childhood home, where her mother Eleanor devolved into religious mania, spewing out ominous prophecies which, to the consternation of her husband, often proved eerily accurate. Lucy’s father, Sir John Davies, was so frustrated by his wife’s “womanish babbles” that he burned Eleanor’s prophecies. She retaliated with a brilliant ploy of reverse gaslighting, foretelling that John would be dead within three years, and thereafter always wearing mourning in his presence to remind him he was about to die. The following winter, she suddenly broke into uncontrollable sobs at the dinner table over the impending death of her husband. Three days later, he dropped dead. Eleanor’s second husband did not learn the lessons of her first. He also burned her prophetic manuscripts in a fit of rage, so by some mysterious power she struck him mute, able only to grunt like a pig.

Eleanor was demonized for her prophecies (and inexplicable ability to silence men) in her time, condemned to the infamous asylum of Bedlam and the Tower of London, but her writings are far from the scribblings of a lunatic. They are complex, literary, and poetic in nature, packed with incisive political commentary masquerading as mystical religious allegory. Was she a raving madwoman, or a proto-Atwood whose resistance against the patriarchy manifested as visions of an apocalyptic future? Lucy’s dedication to her own literary pursuits points toward the latter interpretation. Lucy studied under Bathsua Makin, the most erudite British woman of her time and a radical advocate for the equal education of women. Under Bathsua’s tutelage, Lucy learned French, Spanish, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, and became a pioneering female poet in her own right.

Though Lucy shared Eleanor’s literary gift, as ever, family discord drove a wedge between mother and daughter. Lucy’s father arranged her marriage to Ferdinando Hastings, heir to the Earl of Huntingdon, when she was but 10, and Ferdinando 14. Complicating interfamilial relations, Ferdinando’s mother was Elizabeth Stanley, sister of Anne Stanley, who just happened to be the very same Anne Stanley, Countess of Castlehaven, who married Eleanor’s brother and accused him of sodomy and rape. Adding insult to injury, Eleanor and her daughters in-laws became embroiled in an acrimonious legal battle over her property, with Ferdinando’s relatives trying to transfer control of the estate from Eleanor to the newlyweds on the grounds of her insanity. Eleanor wrote the scathing treatise Woe to the House in response, comparing the Stanley sisters to Jezebel and Satan. When Eleanor was imprisoned because her prophecies spoke truth to power rather too accurately for the King’s comfort, her opportunistic foes swept in, seizing her property in Lucy’s name.

Karma appears not to have taken the Hastings’ side. Parliamentarian forces blew up their ancestral castle during the English Civil Wars, dashing the family fortune to ruin and dooming Ferdinando to debtors' prison. Compounding Lucy and Ferdinando’s misery, three out of four sons died young, but the youngest, Theophilus, was miraculously born 27 years into the marriage and only 18 months after the sudden death of his last surviving brother from smallpox. Regrettably, Theophilus Hastings, 7th Earl of Huntingdon, inherited his family’s less savory attributes, remembered by posterity mainly as a treacherous rogue. His daughter, Lady Elizabeth Hastings (affectionately called Betty), on the other hand, followed in the footsteps of her subversive grandmother and great-grandmother. Pretty, witty, and rolling in money, Betty received no short supply of proposals, but she refused them all. Her correspondence shows she made the conscious choice to remain single and independent to pursue her true passion: promoting women’s education.

Appropriately, it was their female progeny that fulfilled these grande dames' legacies. Katherine Stanhope, Countess of Chesterfield: the ambitious, calculating Royalist, and (if we are to trust in the legitimacy of the fruit of Elizabeth Butler’s loins) 7th great-grandmother of a mighty queen; and Lucy Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon: the woman of letters, pupil of the most learned woman of her time, daughter of a visionary, and grandmother of a proto-feminist heroine. Lucy’s tutor, Bathsua Makin, said, “A learned woman is thought to be a comet that bodes mischief whenever it appears,” and in the case of these two bold countesses, she just may have been right.

Sources

- “Ancestry of Elizabeth II.” Familypedia. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://familypedia.fandom.com/wiki/Ancestry_of_Elizabeth_II.

- Brand, Emily. “Beauty, Sex and Power at the Restoration Court.” The History of Love: Romantic Relationships 1660-1837. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://historyofloveblog.wordpress.com/2015/02/24/beauty-sex-power-at-….

- Brand, Emily. “Beauty, Sex and Power at the Restoration Court.” The History of Love: Romantic Relationships 1660-1837. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://historyofloveblog.wordpress.com/2015/02/24/beauty-sex-power-at-….

- Christie’s. “Sir Anthony van Dyck (Antwerp 1599-1641 London).” Accessed June 11, 2022. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4684727.

- Early Modern Women Poets (1520-1700): An Anthology. Edited by Jane Stevenson, Peter Davidson, Regius Chalmers Professor of English Peter Davidson, 246. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. https://books.google.com/books?id=EynvtQmeW-kC&pg=PA246&lpg=PA246&dq=lu….

- Edwards, Edward. The Life of Sir Walter Ralegh. London: Macmillan, 1868.

- “Elizabeth Lyon.” Prabook: The World Biographical Encyclopedia. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://prabook.com/web/elizabeth.lyon/2414144.

- Feroli, Teresa. Political Speaking Justified: Women Prophets and the English Revolution. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2006. https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-e&q=university+of+dela….

- Ford, David Nash. “Eleanor Touchet, Lady Davies (1590-1652).” Berkshire Royal History. Nash Ford Publishing, 2010. http://www.berkshirehistory.com/bios/etouchet.html.

- Geneanet. “Edward Wotton: Profile.” Accessed June 12, 2022. https://gw.geneanet.org/lard?lang=en&n=wotton&oc=0&p=edward.

- Goodall, John. Ashby de la Zouch Castle and Kirby Muxloe Castle. London: English Heritage, 2011.

- Grumley-Grennan, Tony. Tales of English Eccentrics. Lulu.com, 2010. https://books.google.com/books?id=TXs3AgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&sour….

- Hamilton, Anthony. Memoirs of Counte Grammont. Philadelphia: Gebbie & Co., 1888. https://archive.org/details/memoirsofcountgr00hami/.

- “Katherine Stanhope, Countess of Chesterfield.” Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/6433771.

- Kreis-Schinck, Annette Women. Writing, and the Theater in the Early Modern Period: The Plays of Aphra Behn and Suzanne Centlivre. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 2001. https://books.google.com/books?id=DdYFb6yeX4cC&pg=PA205&lpg=PA205&dq=ba….

- Magdalen College: University of Oxford. “The Life and Library of Arthur Throckmorton.” Last modified September 30, 2015. https://www.magd.ox.ac.uk/libraries-and-archives/illuminating-magdalen/….

- Moxon, Chris. Ashby-de-la-Zouch: Seventeenth Century Life in a Small Market Town. Farnworth: Chris Moxon, 2013.

- Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Edited by Richard Le Gallienne, 78. New York: The Modern Library, 2003.

- Scott, Beatrice. “Lady Elizabeth Hastings.” Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 55 (1983): 95-116. https://archive.org/details/YAJ0551983/page/118/mode/2up.

- Truong, Alain R. “Sir Anthony van Dyck’s portrait of Katherine, Lady Stanhope, later Countess of Chesterfield c. 1635-6.” CanalBlog. Last modified November 23, 2008. http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2008/11/23/11477197.html

- Walker, Peter. The Political Career of Theophilus Hastings (1650-1701), 7th Earl of Huntingdon. Leicestershire: Trans. Leicestershire Archaeol. and Hist. Soc., 1997. https://www.le.ac.uk/lahs/downloads/1997/1997%20(71)%2060-71%20Walker.p….

- Wilkie, Vanessa Jeane. “ ‘Such Daughters and Such a Mother’: The Countess of Derby and her Three Daughters, 1560-1647.” PhD diss., University of Riverside, 2009. https://escholarship.org/content/qt0pg50988/qt0pg50988_noSplash_0c84ea6….

- “Wotton, Edward (1548-1626).” Dictionary of National Biography. Last modified December 29, 2020. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1….

- “Wotton, Edward (1548-1628), of Boughton Malherbe, Kent and London.” The History of Parliament. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/wotto….