More about I Hear Their Gentle Voice Calling

Contributor

Hung Liu may not have lived through the Great Depression, but she was no stranger to poverty.

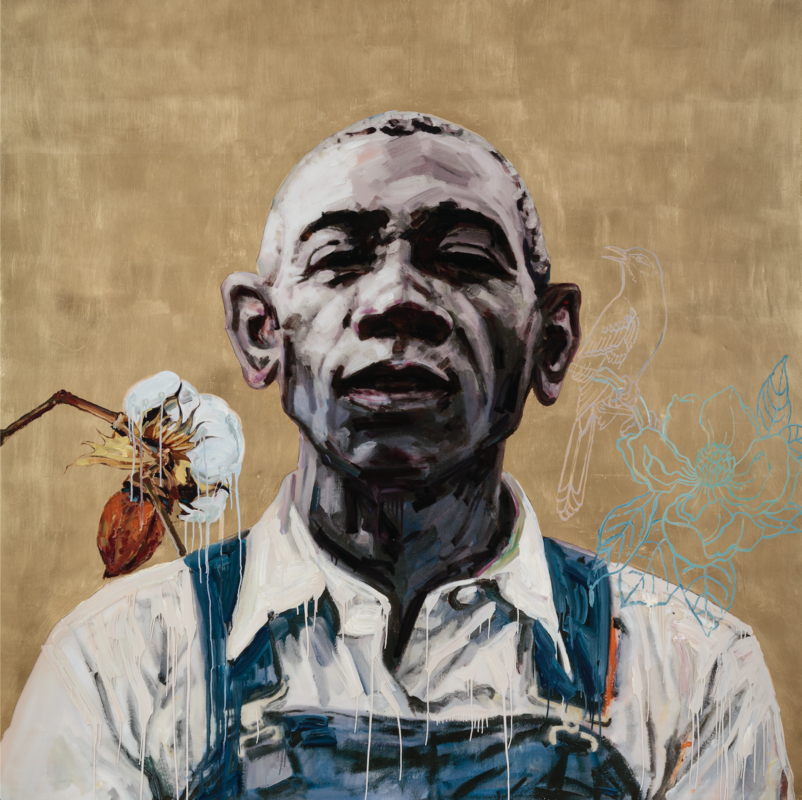

Born in Changchun, China in 1948 under Mao’s Communist Revolution, Liu’s formative years were defined by political and social upheaval. As a young adult, she was sent to the fields as a peasant worker, part of her "proletariat reeducation.” There, she secretly (and very illegally) took photos of her fellow workers and used them as blueprints for her art, sketching their faces when she wasn’t at work. This began Liu’s long relationship with photography, which continued to play a role in her work until the end of her life this past summer. I Hear Their Gentle Voice Calling is an example from a larger series where Liu reimagined historical photographs as vivid portraits.

In interviews, Liu has spoken of her interest in the work of Dorothea Lange— noted photojournalist and very cool woman— specifically speaking of her photography of forced migration during the Dust Bowl. Liu has remarked that she “identif[ies] personally with the work,” referencing the famine, war, and revolution that defined her childhood and forced her and her family to leave their homes again and again. Cotton laborers, often Black workers, were in even worse straits than their fellow migrants. In addition to being forced to leave their lands, they often had no income after the fall cotton harvest and had very few options to make ends meet through the long and dangerous winter. And while the New Deal attempted to make things easier by giving farmers money to share with their workers, many farmers opted to keep the money for themselves and send their workers on their way.

In a work about displacement, it’s notable that Liu chooses to forego a landscape, scrapping the original background for a plain gold. Instead of fields or clouds, Liu adds three very specific symbols to invoke a sense of place; a cotton bud on the left, and a magnolia flower and northern mockingbird, the state flower and bird of Mississippi, on the right. The cotton bud is the only item that exists on the same plane as the man; the branch and the bird remain only as outlines, ghosts of themselves. Considering the vast mistreatment of sharecroppers, it’s easy to read in these symbols the tangibility of present horror versus the elusiveness of hope and life (bird and plant).

It’s not clear who the titular gentle voice belongs to— the bird? the man? marginalized people everywhere?—or if the “I” in the title is even Liu at all. In her work, Liu doesn’t leave us with answers— just with new ways to look for them.

Sources

- BRIA 21 3 a Dust Bowl Exodus: How Drought and the Depression Took Their Toll. (2014, January 1). Constitutional Rights Foundation. https://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-21-3-a-dust-bowl-…

- Mississippi Symbols. (2021). Mississippi Symbols. https://harrison.lib.ms.us/eservices/mississippi/mississippi-symbols/

- Helly, Jeff (1998-2012). Timeline. HUNG LIU. http://www.hungliu.com/timeline.html Lieu, K. M. (2020, December 18). The Dust Bowl. ArcGIS StoryMaps. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/2041c735ed034a3aa077c0b0bc889cce

- Magazine, S. (2021, October 7). The Revolutionary Portraiture of Hung Liu. Smithsonian Magazine.https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/the-revolutionar…