More about Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

This is the story of how Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California by Jules Tavernier came to be:

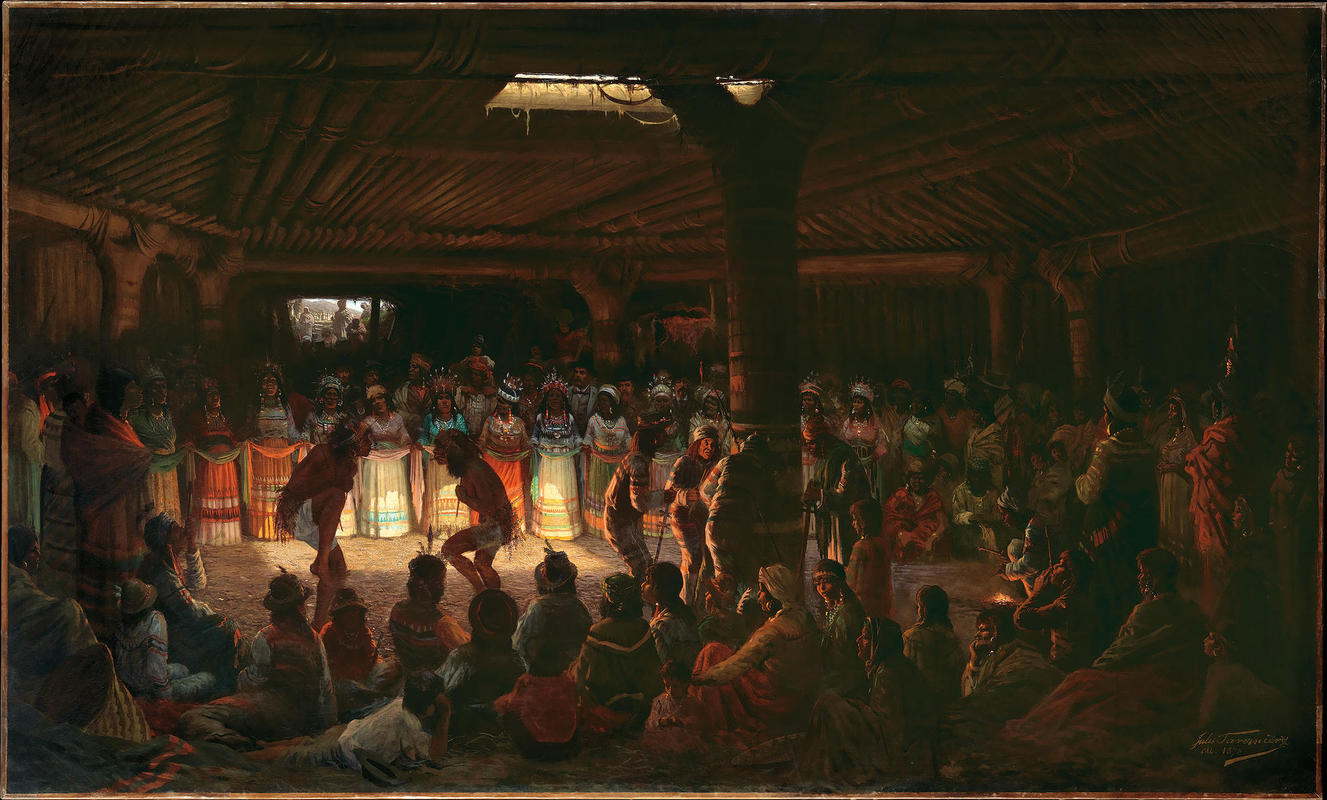

Imagine that your entire community was being destroyed from the ground up by invaders. They came in, used up all your resources, made you sick with foreign diseases, and all of your people struggle to survive. For generations, you had practiced ceremonial routines to protect yourselves. The invaders, while trying to eradicate your culture, were also fascinated by it. So, they asked to come to one of these ceremonies. You allowed them to do so, creating a new dance and ritual for even more enhanced spiritual protection. The invaders asked one of their own to document the entire thing for posterity. That, in a nutshell, is how this painting came to be.

Jules Tavernier was a French-born artist commissioned to depict the American West as he saw it. He came to the San Francisco Bay Area and did just that. On the one hand, he did an impressive job of sharing some of the more authentic truths of indigenous people’s lives. To be invited in to paint this ceremony was an honor, and in a lot of ways, he did it justice. He didn’t slack on the effort either; the ceremony was only a few days long but it took him about two years to create this painting. He paid attention to all the details, recreating the baskets, clothing, and facial features of the indigenous people.

But, of course, as well-intentioned as the work might be, it also encapsulates the problematic issues that arise when a 19th century white man is commissioned to paint an indigenous ceremony. By melding days of ritual into one still image, there are some misrepresentations that don’t accurately reflect the culture. For example, the detailed baskets in the foreground of the painting are a beautiful addition, but they would not have been used in this type of ceremony since these are “everyday” baskets.

Tavernier was commissioned by Tiburcio Parrot, the leading banker in the city at the time, to create this work. He had a business partner from France, Baron Edward de Rothschild, who visited the city for the ceremony as well. Look carefully amongst the 100+ individuals painted in this work and you’ll see those stern men, hats on and mustaches frowning, as they watch the ceremony. They’ve been invited there by the Elem Pomo people to watch this “Mfom xe” or “people’s dance.” And yet, the dance is all about protecting their culture from people like Parrot and de Rothschild.

The dance takes place in the Roundhouse - round, basket-shaped, warm like a hug, it’s been built to protect the people from the catastrophes taking place on the land around them. Their beautiful Clear Lake is being destroyed by the mining practices of white settlers who have come to the West seeking fortune, specifically from the Sulphur Bank Mine that’s polluting their lake with deadly mercury.

Roy Montez, an elder of the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians, explains that the lake is not only important to the people as a critical natural resource, but also psychologically, spiritually, and culturally. In fact, he says that before any of their dances, they must go into the water and dip their heads under in order to cleanse themselves. There is now a sad irony, as they are cleansing in polluted water, perhaps even before the People’s Dance, meant to protect their people from precisely that pollution.

Tavernier’s work was a double-edged sword. On one hand, by capturing the indigenous ceremony for non-native settlers, he was contributing to the problem. On the other hand, by fairly accurately (and powerfully - look at both the detail and the light in the painting) capturing the ceremony and the culture, he also created a legacy to help future generations better understand and honor the Pomo culture. The Pomo people still hold ceremonies in roundhouses in this area today, and still rely on Clear Lake for the water. And the lake is still horribly polluted. The article that quoted Montez was a 2021 California health report on the bacteria in the lake that causes fish, and even a dog who drank it, to die.

Tavernier did the best that he could with the information that he had available to him at the time. He used his skill and talent to try to portray the richness of this culture and this specific ceremony. We know better now, or at least we should, and so we can do better. At the time of the painting, newspapers inaccurately reported on the image using incorrect and even disparaging terms for the Pomo people such as “Coast Indians” or “Diggers,” and sometimes referring to the roundhouse as a “sweat house.” which is not accurate. When Tavernier’s work is shown today, particularly this key painting, it is exhibited with attention to different perspectives on history, and includes input and contributions from the indigenous people whose culture is shown here. This contextualization is important. Speaking at an exhibition of the piece for the de Young Museum in 2021, Elem Indian Colony of Pomo Indians tribal citizen Robert Geary said that, for him, the piece honors his ancestry and showcases traditions that they still perform to this day. He adds, “I guess the ceremony worked because me and my people are still here.”