More about Allover (Genesis, Travis Tritt, and others)

Sr. Contributor

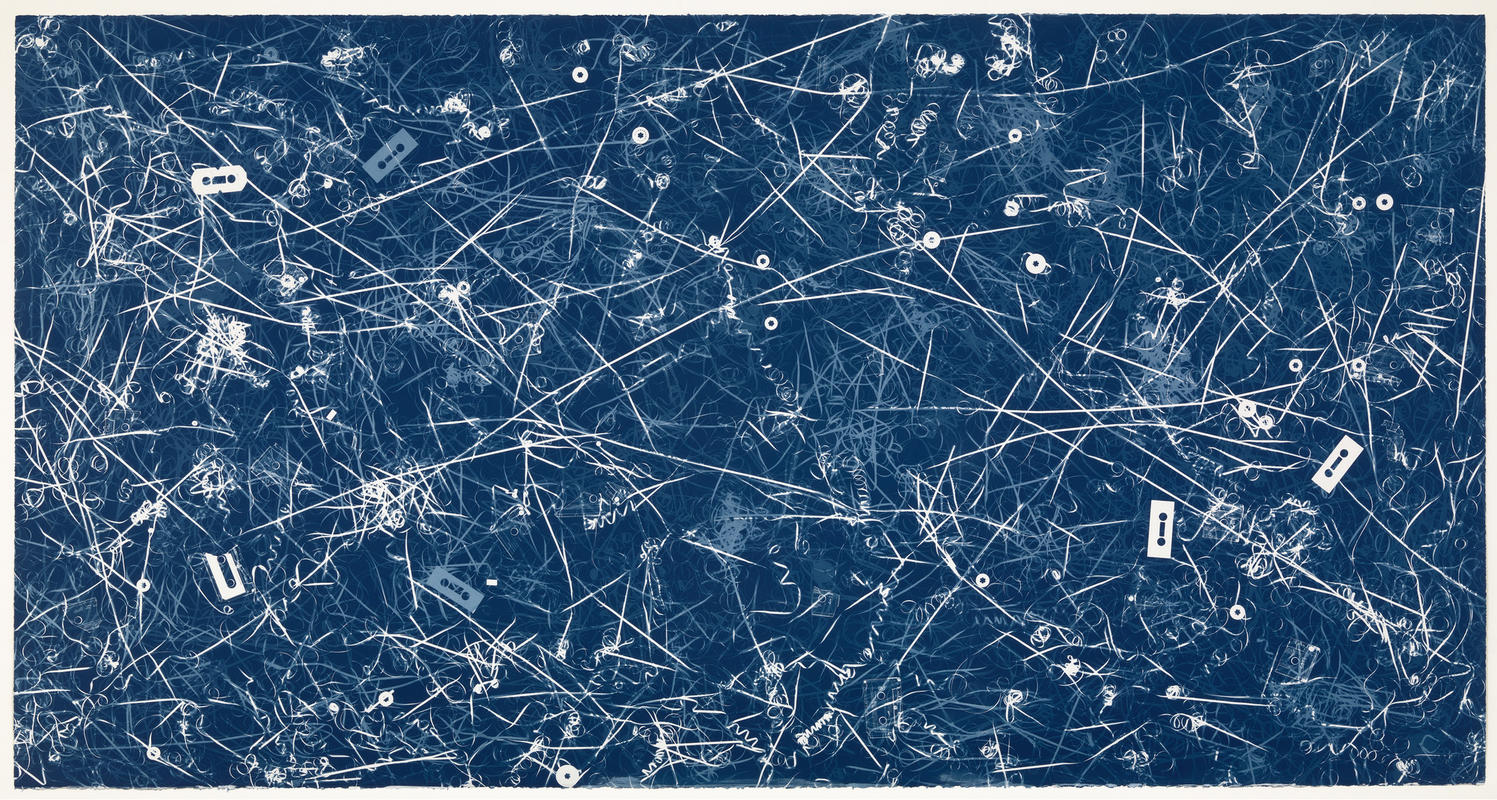

Christian Marclay finally found a use for all of his leftover cassettes from the ‘90s.

As an artist who got his start DJing in New York City clubs, Marclay’s incorporation of the hardware of music is an almost obvious evolution. It’s easy to see how an artist interested in the interplay of sound and image would ultimately use a musical apparatus like a cassette as a visual art tool. Look closely, and you’ll see not only the impressions of cassettes, but also the ribbons of unwound tape strewn about. The swooping lines recall the Abstract Expressionists of the 1950s. It’s not hard to imagine that this looks like what Jackson Pollock might have done if he worked with cassettes and tape rather than paints and canvases.

Marclay’s interest in music served as a common thread throughout his career. From poring over records to extract the perfect sounds to unwinding the magnetic tape from cassettes, Marclay always sought to connect the audio and visual experiences of art and music, as well as explore broader cultural ideas about music. In this case, Marclay deconstructs tapes by major artists like Genesis to consider the role of pop culture and mass-market music.

By 2008, iPods had made cassettes all but obsolete, but Marclay didn’t care about that. Judging by his use of the cyanotype process, he seems to prefer old-school techniques. By creating a cyanotype using cassettes, Marclay cleverly blends two ways that music and art have evolved. Like cassettes, the cyanotype is a traditional mode of art-making that has fallen to the wayside. But this isn’t your average photograph and definitely not the kind that you’d expect to read like a typical photograph.

More specifically, cyanotype is a printmaking process that was developed in the early days of photography. Because the blue background is sensitive to ultraviolet light, it is a photographic process. By placing treated paper in sunlight, you expose an image onto the paper. Sometimes called a sun print, a cyanotype can involve objects, like flowers and plants or even cassettes, laid on top of the light-sensitive ground. When he invented the process in 1842, Sir John Herschel named the cyanotype after the Greek word “cyan,” meaning a dark-blue impression. I’m willing to bet that Herschel never thought that pieces of plastic that play music would become an ironic statement on aging art techniques. No one could have predicted that the translucent plastic of the cassette would make the perfect filter for light and uncover a whole spectrum of the cyanotype blue.

Sources

- Art21. “Christian Marclay.” Artists. https://art21.org/artist/christian-marclay/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA2sqOBhCGARIsA…. Accessed 6 January 2022.

- Fraenkel Gallery. “Christian Marclay: Cyanotypes.” Exhibitions. https://fraenkelgallery.com/exhibitions/christian-marclay-cyanotypes. Accessed 12 January 2022.

- Loos, Ted. “Cyanotype, Photography’s Blue Period, Is Making a Comeback.” The New York Times. Art & Design. 5 February 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/06/arts/design/cyanotype-photographys-b…. Accessed 12 January 2022.

- Museum of Modern Art. “Allover (Genesis, Travis Tritt, and others).” Collection. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/156674?classifications=any&date_b…. Accessed 12 January 2022.

- National Science and Media Museum. “Introduction to the cyanotype process.” Blog. 18 February 2011. https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/introduction-cyanotype-proces…. Accessed 12 January 2022.