More about James Ensor

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

Fed up with the Manets and Renoirs of the world, James Ensor embarked in a bold artistic direction all his own.

Guess you really can't take back first Impressions...ugh, Jesus, we're so sorry.

It's a special kind of person who decides, in the middle of Europe's love affair with the Impressionists, that what the public really wants is piles of creepy masks, pissed-off skeletons and loads and loads of fish monsters. It's not like James Ensor didn't get the memo that Impressionism was a big deal—most of his friends were artists, so it definitely came up in conversation once or twice, and his art collective (Les XX, or Les Vingt, for those of our readers fluent in French but not Roman numerals) invited such Impressionist legends as Monet and Cézanne to exhibit with them.

It's just that, despite all that, he didn't really care. Sure, he experimented with Impressionist techniques in his early years—he was young, everybody was doing it, you know how it is—but it didn't take him long to decide that his true calling lay more with the Goyas of the world. He became infatuated with the power of light and its ability to distort lines, which were to him the “enemy of genius,” and from 1885-86 he poured his heart and soul into a series of moody, haunting images called The Haloes of Christ, or the sensitivities of light. Unfortunately, when the series went on display at the Salon des XX the public didn't share his enthusiasm, instead saving the lion's share of their praise for Seurat's now-iconic Grande Jatte, a piece whose precise pointillism was the opposite of everything Ensor stood for.

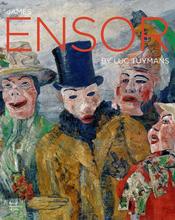

That poor showing against Seurat seems to have stuck in Ensor's craw a bit, because as the '80s progressed he didn't so much let his freak flag fly as strap rockets to it and launch it into the stratosphere. Seaside still-lifes and earnest explorations of Christ's torments gave way to works with titles like Skeletons Fighting Over a Pickled Herring (1891), My Aunt Asleep Dreaming of Monsters (1888) and The Grotesque Singers (1891). The public's uncomfortable reaction to this new and crazy direction only served to encourage him. By the mid 1890s if you showed James Ensor something the public loved, he'd show you a demi-human clown orgy.

Despite the surreal nature of Ensor's imagery, a great deal of it was drawn from his personal life. His lifelong fascination with masks had its origins in his mother's souvenir shop, where he spent a great deal of time as a child; the numerous masks he saw on display there fueled his imagination from an early age. Though he was a lifelong atheist, Ensor strongly identified with the figure of Jesus on the basis of their mutual experiences with public shame and humiliation in pursuit of their callings. As such, JC shows up in a bunch of Ensor paintings, most notably 1889's Christ's Entry into Brussels, widely considered to be his masterpiece. Similarly prominent in Ensor's work is the image of a pickled herring, due to the fact that the French term for it (hareng saur) is pronounced nearly identically to art Ensor, which is, uh, conceivably a combination of words somebody might use when talking about him. Look, not everybody in the 1800s was Oscar Wilde, all right?

The downside to being an iconoclast is that one eventually runs out of icons to clast at. No matter how inventively one thumbs one's nose at the status quo (or dresses it up in freaky masks, as the case may be), if one can't keep people guessing then one tends to find oneself uninvited from the better kinds of parties. So, after years spent successfully establishing himself as a scandalous voice of his generation's collective id, Ensor didn't really do a whole lot worth mentioning. He dabbled all over the place—did some writing, composed some music, kept a hand in the ol' painting and engraving game—but once the 1890s were over his oeuvre got pretty repetitive, and the accolades he received in his later years were mostly in honor of the stuff he'd done decades prior. This is perhaps why one so frequently hears Paul McCartney described as “the James Ensor of Rock Music” [citation needed].

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about James Ensor

James Sidney Edouard, Baron Ensor (13 April 1860 – 19 November 1949) was a Belgian painter and printmaker, an important influence on expressionism and surrealism who lived in Ostend for most of his life. He was associated with the artistic group Les XX.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about James Ensor