More about The Mosque

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

Ibrahim el-Salahi is no stranger to disruption.

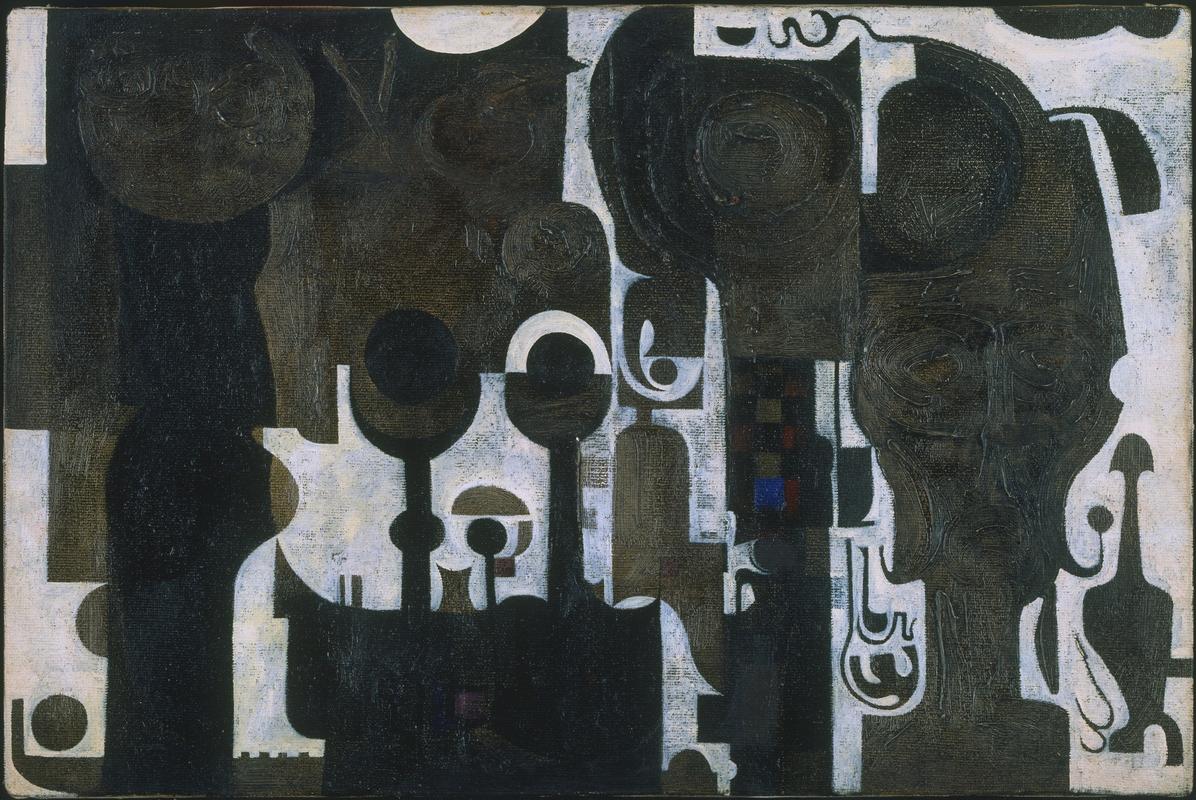

In a quiet world reminiscent of the dreamy scenes of Paul Klee, two minarets rise up and assert their place in the midst of what might otherwise be construed as Western, modernist abstraction. This blending of Western styles and Islamic symbols is a product of Salahi’s upbringing – first in the Islamic state of Sudan and then in London where he attended art school and was inevitably taught the Western modes of art production.

Salahi has earned the moniker of African Surrealist, and, as with any good Surrealist, his works toe the line of familiarity. But he always adds something that doesn’t quite jive with the Western sensibility...in the best possible way. This was perhaps what Alfred H. Barr Jr., the notorious first director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, noticed about The Mosque when he first saw it in 1965. Barr must have realized that Salahi had a certain je ne sais quois because he bought the piece directly from the artist. Sadly, after The Mosque debuted in a recent acquisitions exhibition that same year, it sat in storage and remained unseen for another fifty-two years.

MoMA finally busted out Salahi’s small, yet powerful work after Donald Trump’s January 2017 travel ban on citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries, including Sudan. The ill-advised executive order characterizes a strange time in American history, and MoMA declared an institutional position through the art that was on view in their galleries. Curators hauled works by artists from the seven banned countries out of storage and installed them throughout the museum’s fifth-floor permanent collection galleries.

The works provided a much-needed disruption to the same-old, same-old that’s always on display in this space. Since its inception, MoMA has told a Western-centric narrative of modern art, tracing its development as a linear progression starting with Cezanne, continuing through Picasso, and up to Pollock, leaving little to no room for non-Western artists. Taking down some of these works by “the greats” and introducing the world to names such as Salahi and Parviz Tanavoli was a bold move for the museum to stick it to the man in a subtle, yet pointed way.

The Mosque had its time to shine for a short while. The painting hung across from Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, one of the museum’s most infamous works on view, except of course for The Starry Night.

Sources

- Balaghi, Shiva. “MoMA’s Travel Ban Protest Exposes a Legacy of Closeted Modernism.” Hyperallergic. March 15, 2017. https://hyperallergic.com/365397/momas-travel-ban-protest-exposes-a-leg…. Accessed March 9, 2018.

- Farago, Jason. “MoMA Takes a Stand: Art from Banned Countries Come Center Stage.” The New York Times. February 13, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/03/arts/design/moma-president-trump-tra…. Accessed March 9, 2018.

- Museum of Modern Art. “Ibrahim El-Salahi. The Mosque. 1964.” Collection. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78385. Accessed March 9, 2018.

- Shaw, Anny. “Sudanese artist’s haunting images of prison come to MoMA.” News. The Art Newspaper. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/sudanese-artists-haunting-images-o…. Accessed March 9, 2018.