More about The Great Avalanche of 1905

Contributor

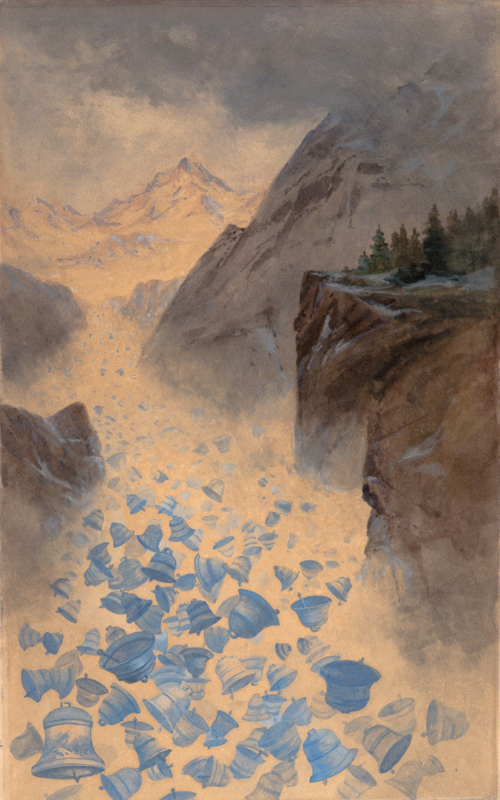

The Great Avalanche of 1905, or 10,000 Bells, marks a fascinating—and in some ways, frighteningly prescient—departure for the painter’s usual “cowboy art.”

Charles Marion Russell worked in a similar fashion to artists such as Frederic Remington and created realistic, yet strongly atmospheric paintings of the 1800s American West. His art, depicting the lives of cowboys, cattle drivers, and Native Americans, illustrated the hardships and beauty of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains for those in the industrialized Eastern cities. Russell’s work often had an air of nostalgia for the lost landscape, before the period of white American imperialism known as “westward expansion” caused unprecedented ecological and cultural catastrophe among indigenous populations. His sympathy for the situation of Native Americans is a pleasant surprise amid mainstream contemporaneous racism. In a biography otherwise predictable in its ethnic stereotypes, Russell’s nephew Austin quotes him as saying, “The white man kills off the buffalo, takes the Indians' land, deprives him of his only means of livelihood, refuses to hire him as a ranch hand, and then tells you that all Indians are lazy, a bunch of stinking gypsies!"

Russell created this particular painting during a time of his life when he spent his summers in the north of Montana’s Glacier National Park, with alpine trips to Avalanche Basin. However, the artist’s personal experience is where the painting’s connection to real, relevant events seems to stop. Records of historical avalanches in the area are spotty at best, and there is certainly little evidence of anything that could be described as a “great” avalanche that Russell intended to commemorate with a painting. Even the mountains in the background don’t match the Avalanche Basin skyline. Plus, the scene is not only fictional, it is highly fantastical and dramatized—instead of the expected slab of snow or slide of rocks, the avalanche itself is represented by a mass of huge bells.

The bells make some sense—anyone with mountaineering background can attest to the incredible sound that avalanches make. The “whumph” of the snowpack breaking and the roar of material coming downhill signify the advent of a force of nature that can kill or injure any living being in its path and destroy infrastructure. The cascade of bells accurately reflects the sort of alarm and terror any experienced skier, snowboarder, or hiker might feel upon hearing such noises.

However disastrous an avalanche may be, mountain ecology requires their occasional disruption to remain balanced. In the same way that forest fires clear brush and trigger the growth of certain plants, avalanches create regular open spaces along their consistent paths, enabling the growth of flowers and low plants that require more light and water than they would otherwise get in a dense, high alpine forest. In the slide paths of an avalanche, meadows can form, adding to the habitat diversity in the range. The snow pushed downhill and consolidated also provides an additional source of meltwater for plants and animals in the spring.

As a natural feature of the environment, avalanches are a crucial part of the overall biosphere and geography. They are also highly dependent on weather, which, of course, is subject to extreme and unprecedented change as the global climate grows warmer. Scientists working in this field have been unable to determine whether global warming will cause avalanches to be more common or more rare. Neither of these options is good—more avalanches pose a threat to human activity, while fewer avalanches may upset the already delicate balance of the ecosystem. Charles Marion Russell could not have predicted the scope of the damage, but even in his time, he was preoccupied with anthropogenic (i.e., caused by humans) ecological disaster, as he witnessed firsthand things like the near-extinction of buffalo. The Great Avalanche of 1905, like many of Russell’s landscape paintings, reflects his concern with both individual and environmental catastrophe, in a way that even twenty-first century viewers can understand.

Sources

- Sasnet, Peri. “Glacier’s Avalanche Cycles: Past, Present, and Future.” National Park Service, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/articles/avalanche_research.htm

- Russell, Austin. Charles M. Russell, Cowboy Artist: A Biography. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1957. See esp. chap. 13, “Charlie in Montana,” and chap. 18, “Charlie and the Indians.” http://www.archive.org/stream/cmrcharlesmrusse010044mbp/cmrcharlesmruss…

- Gale, Robert L. Charles Marion Russell. Boise: Boise State College, 1927. http://digital.boisestate.edu/cdm/ref/collection/western/id/30