More about Peregrine Falcons (Duck Hawks)

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

John James Audubon’s oil painting Peregrine Falcons (Duck Hawks) depicts one of the most impressive North American birds of prey in its (almost) natural habitat.

Peregrine falcons, also known as duck hawks or great-footed hawks, prey on ducks, shorebirds, and songbirds. They are built to kill with large talons, a sharp curved beak, and black feathers under their eyes that act like black eye grease to block the sun's glare. Peregrine falcons are the fastest birds in the world, reaching over 240 miles per hour as they dive for prey. This speed comes in handy while the falcons are completing their annual migration which can be up to 15,500 miles long.

The history of this incredible bird is complicated. Peregrine falcons were once found nesting all across the world. They were the favorite choice for falconers since before Medieval times and were a symbol of speed and agility. However, peregrine falcons were never a very populous species and records show that in the late 18th century, the number of peregrine falcons in North America was noticeably low. Due to unknown causes, there was a spike in their numbers during the 19th century, but this age of plenty would not last for long. Between 1947 and 1970, the number of peregrine falcons decreased at an astronomical rate, the population nearing extinction because of the agricultural pesticide DDT. DDT contaminated the soil and water of the peregrine falcon’s habitats which negatively affected their reproduction. When directly and indirectly exposed to DDT, the peregrine falcon’s eggshells became extremely thin, meaning many of the eggs broke during incubation or never hatched. The epidemic became so devastating that the peregrine falcon was deemed critically endangered. After DDT was banned in 1972, a massive rehabilitation program began for the peregrine falcons in which they were bred and raised in captivity before being released into the wild. Thankfully, this effort was not in vain, for today peregrine falcons are no longer on the endangered list and their numbers are on the rise.

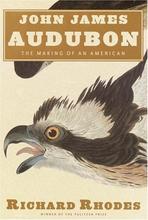

John James Audubon was lucky enough to observe the peregrine falcons during their baby boom in the early 19th century. In the 1820s, he spent five years traveling across the diverse terrain of North America drawing and studying every kind of feathered friend he encountered. He observed the two falcons in Peregrine Falcons (Duck Hawks) separately and combined their likeness into one grand composition. Audubon first saw the falcon on the right, which is the female, while on an expedition down the Mississippi River in 1820. In his four-part publication "The Birds of America," Audubon recounts coming across almost 50 peregrine falcons before shooting this particular female to perform a dissection. The dissection uncovered the bird’s diet which included the “gizzard of a Teal." Audubon used this information to guide his holistic depiction of the falcons, showing the birds feasting on a green-winged teal duck. Four years later, on a trip near Niagara Falls, Audubon finally came across a worthwhile mate for his lonely peregrine lady. He shot and then drew the male falcon on the left in Peregrine Falcons (Duck Hawks) in August 1824. Peregrine falcons are solitary animals, but Audubon chose to place both falcons in one composition to make it more engaging. Even though the artwork is not exactly accurate, it is a fine homage to this imposing and strong-willed predator.

Sources

- Audubon, John James. “Great-footed Hawk.” Audubon’s Birds of America. National Audubon Society. Accessed October 24, 2021. https://www.audubon.org/birds-of-america/great-footed-hawk.

- “John James Audubon, Part 3.” Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Last modified September 27, 2014. https://crystalbridges.org/blog/john-james-audubon-part-three/.

- “Peregrine Falcon.” State of Tennessee, Wildlife Resources Agency. Accessed October 24, 2021. https://www.tn.gov/twra/wildlife/birds/waterbirds/peregrine-falcon.html.

- “Peregrine Falcons (Duck Hawks).” Cleveland Museum of Art. Accessed October 24, 2021. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1964.351.

- Rhodes, Richard. “John James Audubon: America’s Rare Bird.” Smithsonian Magazine. Last modified December 1, 2004. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/john-james-audubon-americ… -97819781/.

- Zimmerman, David R. “Death Comes to The Peregrine Falcon.” The New York Times, August 1970. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/08/09/archives/death-comes-to-the-peregrin… h-comes-to-the-peregrine.html?smid=url-share.