More about Pasadena Lifesavers Red #5

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

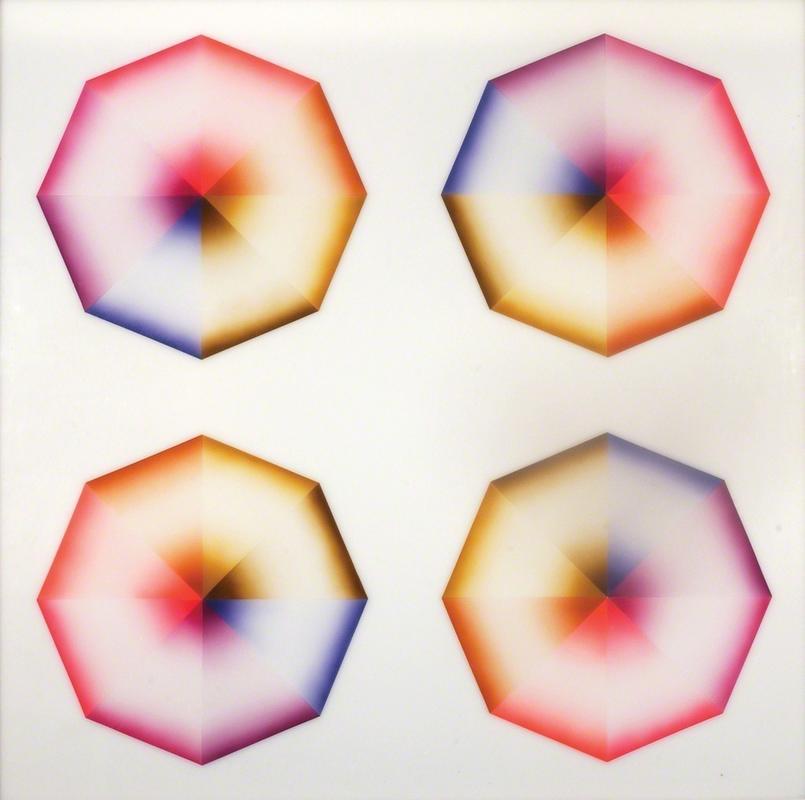

Judy Chicago's early works, like these Lifesavers, were the foundation of her “central-core” imagery.

Before creating her feminist manifesto, Chicago had to navigate the predominantly-male art world in all its painful machismo. Los Angeles in the 1960s was glitzy and glamorous, and art trends followed suit. Everyone was obsessed with the Los Angeles Look, art that incorporated the popular look and materials of airbrushing surfboards and carts. Her lifesavers show off the skill and control that she developed with this particular medium.

The art world has always been a boys’ club, and the L.A. Look crowd, which boasted artists like Ed Ruscha, was certainly no exception. Chicago experienced this firsthand. She learned to airbrush car hoods at auto-body school, where she was the only woman in a class of 250. To keep up with the sausage fest, she developed her own brand of machismo, perhaps taking a few lessons from Rosa Bonheur who cut her hair short and wore pants to see the beloved animals that she enjoyed painting.

After getting past the fact that she was one of the only women successfully working within this realm, Chicago realized that she was actually really good at this type of airbrushing. She mastered the technique and began to utilize these unorthodox, industrial materials in her fine art paintings. However, she soon realized that her womanhood and the subjugation that she experienced because of her gender would not allow her to just paint any old types of colors and shapes. Inevitably, vaginal imagery seeped into these works that were also just abstract enough to allow for open-ended interpretation.

Although if you really wanted to see that in this work, you totally could. I mean, Georgia O’Keeffe achieved the flowing, feminine forms through abstract imagery. Even before she began creating consciously feminist work, like her famous Dinner Party, Chicago was a force to be reckoned with.

Sources

- Franklin Parrasch Gallery. “L.A.’s Finish Fetish.” Press Release. http://franklinparrasch.com/exhibitions/2003_9_las-finish-fetish/pressr…. Accessed 16 February 2020.

- Jansen, Charlotte. “At 80, Judy Chicago is finally being recognized for the full range of her work.” Style. CNN. 12 December 2019. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/judy-chicago-artsy/index.html. Accessed 16 February 2020.

- National Museum of Women in the Arts. “Judy Chicago.” https://nmwa.org/sites/default/files/shared/sfy_chicago.pdf. Accessed 16 February 2020.

- National Museum of Women in the Arts. “Pasadena Lifesavers Red #5.” Explore. https://nmwa.org/works/pasadena-lifesavers-red-5. Accessed 16 February 2020.

- Rivenc, Rachel, Emma Richardson, and Tom Learner. “The L.A. Look from Start to Finish.” Modern Materials and Contemporary Art. The J. Paul Getty Foundation. 2011. https://www.getty.edu/conservation/our_projects/science/art_LA/article_…. Acc

- The Art Story. “Life and Legacy, Judy Chicago.” Artists. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/chicago-judy/life-and-legacy/. Accessed 16 February 2020.