More about Mouse Heaven

Contributor

“Mouse Heaven” was Kenneth Anger’s affectionate nickname for the personal Disney treasure trove of toy designer and antique collector Mel Birnkrant.

Picture a room with mood lighting and elaborate display cases, crammed with vintage Mickey Mouse memorabilia of every variety, from every era. Anger first coined the moniker years before the creation of the short film of the same name, so the kinda-creepy collection was the film’s original inspiration (and its set). It took two rounds of funding to make Mouse Heaven happen. Anger’s projects were often backed by moneybags oil heir Paul Getty. In 1986, Getty gave Anger $100,000 to make the film. Instead, Anger spent that money on things such as a luxury vacation in Washington DC. I can’t really imagine why, but in 2004, Getty offered Anger more money (a modest $35,000) to shoot the film for real. Second time was the charm.

Anger felt passionately that the degradation of the Mickey Mouse franchise over the years was a commercial betrayal of a beloved character. The film picks at overblown Disney consumerism by glorifying Mickey’s earlier avatars, from creepy old Depression-era puppets to cheery animations. The Mickey that Anger knew and loved as a child had since become a tailless, “castrated” ghost of his former self. “He’s no longer the mischievous, sadistic mouse that he was in the beginning,” laments Anger. “He used to do nasty little tricks like twist the udders of cows and things like that. And that’s the only mouse I’m interested in, I mean this kind of demon ‘fetish’ figure.”

To further delve into the dark side of Mickey Mouse, Anger draws some thematic and stylistic parallels between Mouse Heaven and another of his short films, "Ich Will!," which centers on Hitler youth. He reasons, “Cultural critics say that the two most famous and popular images of the 20th century are the face of Mickey Mouse and the swastika.” Make of that what you will.

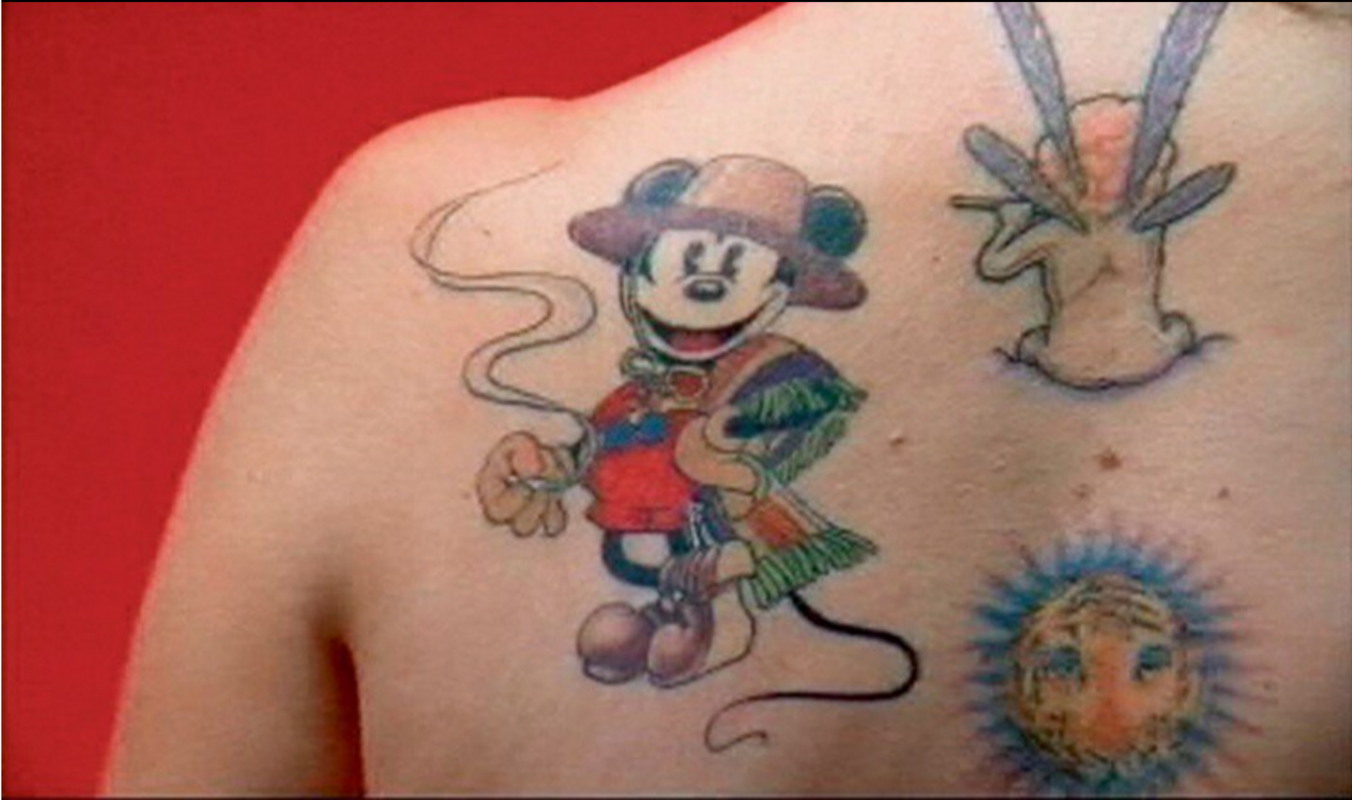

The shot of the Mickey-Mouse-dressed-as-Rudy-Valentino tattoo? That’s actually on Birnkrant’s daughter, Alexandra’s, shoulder. It’s a drawing he originally gave to Anger (framed and on paper) as a birthday gift. As an appreciator of bizarre tattoos, Anger couldn’t resist putting a good close-up in the film.

Sources

- “An Evening with Kenneth Anger: Dangerous Cinema,” Redcat, accessed April 30 2017, https://www.redcat.org/event/kenneth-anger

- Jerry Beck, “Mouse Anger,” Cartoon Brew, January 7 2005. Accessed April 30 2017, http://www.cartoonbrew.com/old-brew/mouse-anger-756.html

- Mary Hanlon, “New Films from Kenneth Anger,” The Brooklyn Rail, July 9 2009. Accessed April 30 2017, http://brooklynrail.org/2009/07/film/new-films-from-kenneth-anger

- “Mel Birnkrant’s Kenneth Anger,” accessed April 30 2017, http://melbirnkrant.com/recotwo/page2.html