More about Fish and Sky

Sr. Contributor

Whoever coined Michael Jackson as the “King of Pop” clearly didn’t know anything about Roy Lichtenstein.

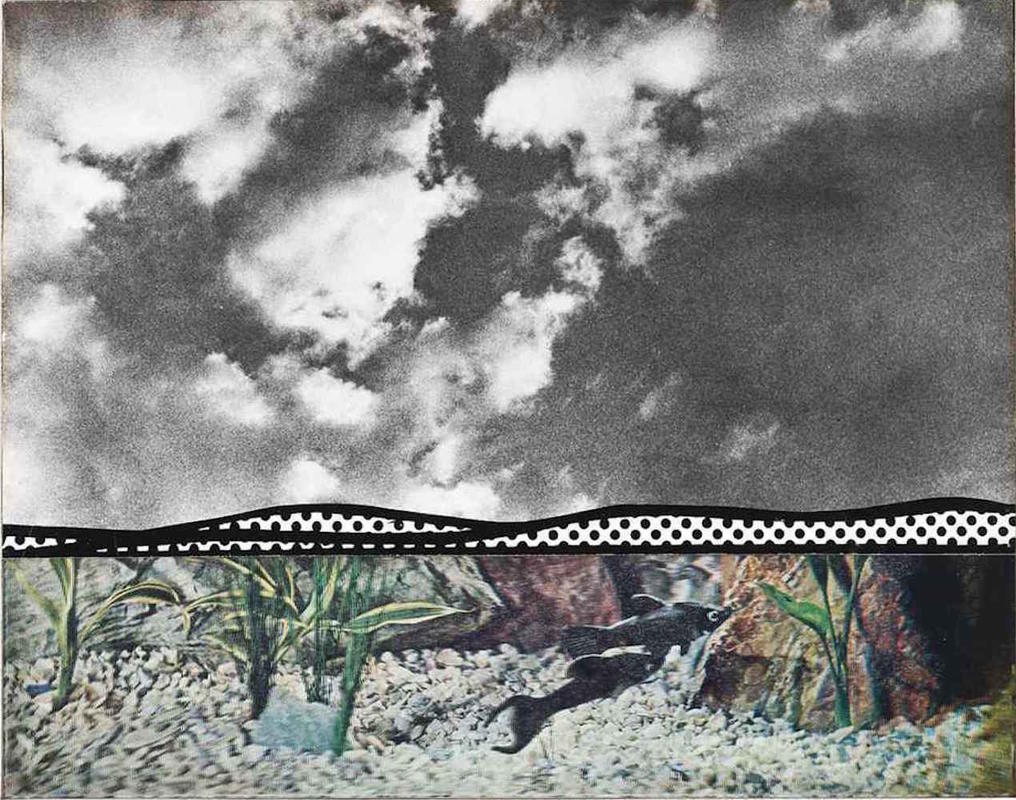

Lichtenstein revolutionized the art world by giving it a sense of humor (the horror!) and playing on the way images appear in mass-cultural productions. His dot-happy style of painting was inspired by the Ben-Day dots that gave printed comics their colors, and the dots eventually made their way into works other than paintings.

Growing up in Manhattan, Lichtenstein might have gotten the idea to make paintings and other artworks look like comics by going to the local comic book shop, but we can actually trace this inspiration to the time that he served in World War II. In 1943 at about twenty years old, Lichtenstein was drafted into the army, where some of his responsibilities included working with comics. Unfortunately, comics weren’t always as lighthearted as Family Circus and Garfield. When America was involved in World War II, many newspaper cartoons dealt with the subject of war. Lichtenstein enlarged these types of newspaper political cartoons and comics for his commanding officer.

Early in his forays into Pop art, Lichtenstein painted landscapes that he copied from the backgrounds of frames in comic books. In fact, many of his early Pop works are pretty much just blown-up copies of comic book frames. By 1967, he decided to shake things up by adding his now-infamous dots to works that incorporated photographs. The end result is a weird optical illusion that Yayoi Kusama could definitely get behind.

Fish and Sky was one of ten works commissioned to celebrate the ten-year anniversary of New York City’s Leo Castelli Gallery. Castelli was one of the head honchos of the New York art world and, in ten short years, built an art empire that basically built the “who’s who” of the insufferably hip scene. This group of ten works, called Ten from Leo Castelli, was a portfolio that featured ultra-famous artists. Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, Lee Bontecou, Donald Judd, Larry Poons, James Rosenquist, and Robert Morris all made works to commemorate their beloved gallerist and dealer. Each of the works made was created in an edition of only 200 copies. If you happen to have about $30,000 lying around, you can even pick up your own edition of this Lichtenstein print. And make sure you get one for me, too.

Luckily, LACMA has friends in high places. The institution’s Ralph M. Parsons Fund helped the museum acquire this work. You might be asking yourself, who is this Parsons guy, and why does he have enough money to have an entire museum fund named after him? A self-made millionaire, Parsons was an engineer with a soft spot for photography. Proving that really rich guys can also be cool, the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation began as a small, charitable sector of the Parsons Company and has since grown to support many programs and organizations throughout Los Angeles County, including LACMA. Currently, over 1,600 photographs in LACMA’s collection, including Lichtenstein’s part-photograph part-Pop wonderland, were purchased with the help of this fund.

Sources

- Roy Lichtenstein, The Art Story, http://www.theartstory.org/artist-lichtenstein-roy.htm.

- Roy Lichtenstein: A Retrospective, Art Institute of Chicago, http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/exhibitions/Lichtenstein/themes/La….

- Fish and Sky, Philadelphia Museum of Art, https://philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/62593.html?mulR=173615336…

- Ten from Leo Castelli, Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/portfolios/78135?locale=en&page=1…

- Fish and Sky, Peter Harrington London, http://www.peterharrington.co.uk/fish-and-sky.html

- Fish and Sky, LACMA, https://collections.lacma.org/node/196540

- https://collections.lacma.org/search/site/ralph%20m.%20parsons