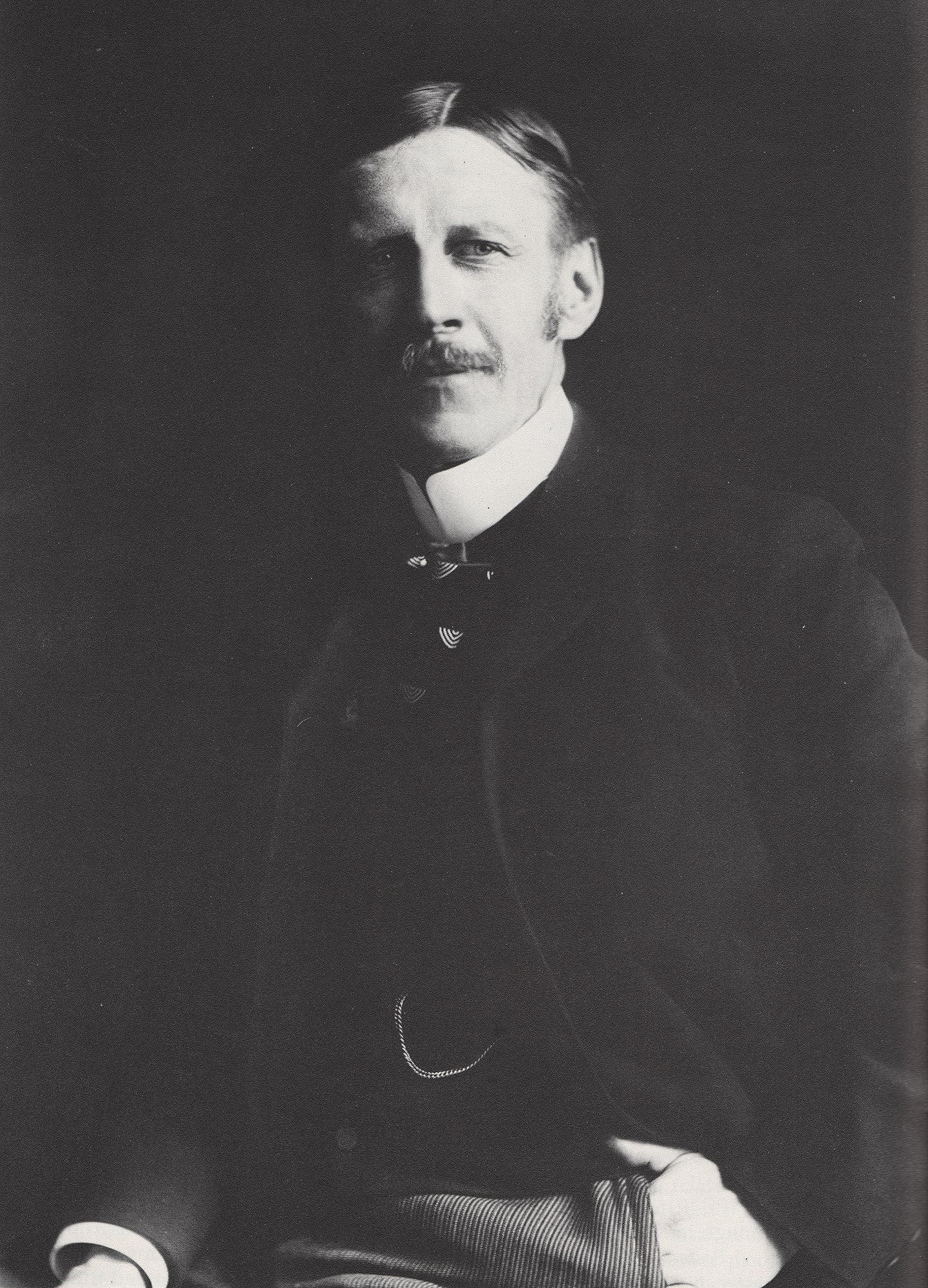

More about Richard Norris Brooke

Works by Richard Norris Brooke

Contributor

When the Civil War hit his birthplace of Warrenton, Virginia, Richard Norris Brooke was a little too young to fight,.

But he would have seen the ways in which issues of sovereignty, federal unity, the slave trade, and land ownership were capable of tearing apart both families and states. Warrenton became the site of an ugly custody battle between Confederates and Unionists, changing occupiers sixty-seven times.

As a young man, Brooke studied with Léon Bonnat, teacher of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Thomas Eakins, and Gustave Caillebotte, at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He returned to the States at the age of thirty-three, just in time to snag the big fish of political commissions, an assignment from the U.S. House of Representatives to portray Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall. The Marshall portrait still hangs in the Capitol building.

With a successful practice and an office in D.C., Brooke wanted to go back to basics and portray the lives of locals in Warrenton, about fifty miles away. Brooke wanted you to know that the town represented, like the city of D.C. itself, another side of the Republic, the side of the people whose ancestors came to the Land of the Free in chains. In several works, especially his most famous one, The Pastoral Visit, Brooke did his best to portray the Black people of Warrenton in a way that paid homage to the portraiture of Bonnat and the sensitive agrarian scenes of Jean-François Millet, as well as, in Brooke's words, "that plane of sober and truthful treatment which...has dignified the Peasant subjects of Jules Breton, and should characterize every work of art.” The National Gallery of Art gives the title as A Pastoral Visit, but leading Warrenton-ologist, retired FBI agent, tall clock expert, and Brooke authority Walt H. Sirene establishes that the correct title is The Pastoral Visit. He's also revealed the identities of many of Brooke's Warrenton models. The elderly man in The Pastoral Visit, for example, also features in other Brooke works, and his name is George Washington, writes Sirene.

For journalists, Brooke's work with Black people was an excellent "scoop"—he has "made negro life interesting to us with his brush," one of his very interviewers writes of the fifty-year-old artist in the pages of an education journal. At this point, in the midst of detailing the way in which Brooke tells "funny stories" about his local subjects, the narrator casually drops a racial slur. I wanted to quote it to give a sense of the climate Brooke was dealing with, but, after sixteen hours of hemming and hawing and two espresso shots, I changed my mind. I don't know if I'm making the right decision or not. That kind of language was totally acceptable among self-identified whites in Brooke's cultural environment, because it seemed to offer the possibility of putting the Humpty Dumpty of the slave trade back together again. Since the interviewer is, after all, recommending curricula for schoolchildren, the profile of Brooke ends with an outline of a chronological lesson plan entitled "The Negroes," beginning with the "Condition of the Negroes in Africa" and concluding with the "Effect of Mingling with White Men," and "The Negro Question of To-day." The National Gallery of Art's website says that, for "unknown reasons," Brooke focused exclusively on unpeopled landscapes in his later career. Maybe we can guess at why.

At twenty-five, Brooke had done a cartoon for Harper's Weekly called "canvassing for votes," showing the distinct dangers of the Northern "carpetbagger"—a Black man with an Anton LaVey beard, straightened hair, a shiny top hat and expensive shoes, hovering, hands clawing like Shakespeare's Shylock, at a poor Southerner, whose shoes and clothes are rumpled. The fear was that Northerners would radicalize the newly enfranchised local Black people, turning them against the politicians who'd fought tooth and nail to keep them enslaved.

When Brooke was sixty-two, a catastrophic fire swept through Warrenton, destroying the studio he'd built ten years earlier, along with 225 of his works, which were worth at least $25,000, the equivalent of over $660,000 in today's purchasing power.

An architectural Brooke painting of the U.S. Supreme Court served as an appearance reference for the Court's interior restoration during the Nixon Administration.

Sources

- "A Pastoral Visit." National Gallery of Art, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.166432.html#overview.

- Mack, Gerstle. Toulouse-Lautrec. Lexington, MA: Plunkett Lake Press, 2019.

- "Richard Norris Brooke." Smithsonian, https://americanart.si.edu/artist/richard-norris-brooke-592.

- School Education, Volume 17. Minneapolis: School Education Company, 1898.

- Sirene, Walt H. Richard Norris Brooke - A Photographic Exhibition: Warrenton Virginia's Celebrated Artist. Warrenton, VA: Self-published, 2019.

- Sirene, Walt H. Richard Norris Brooke - Artist - Record of Work: “Serving to some Extent as a History of my Professional Life And As a means of Tracing Pictures and Studies Painted and Disposed of Especially Since my departure for Paris in 1878”. Warrento

- Toler, John T. "Warrenton historian uncovers traditional and new ways to look at the past." Fauquier Times, Jan. 31, 2019, https://www.fauquier.com/news/warrenton-historian-uncovers-traditional-…

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Richard Norris Brooke

Richard Norris Brooke (October 20, 1847 - April 25, 1920) was an American painter known especially for his genre scenes depicting African-American subjects. He has been described as "first among several artists who brought a national distinction to the Washington art community, and who were instrumental in making it more professional through the establishment of schools, clubs, and exhibitions."

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Richard Norris Brooke