More about Olin Levi Warner

Works by Olin Levi Warner

Contributor

He wasn't as young as Antoine Watteau or Theodore Gericault, but the imaginative sculptor Olin Levi Warner still had decades of breath left in him when he was in a tragic horse-drawn carriage accident in New York City, ending a marvelous career.

Whether it was due to a bad astrological chart, a flaky designated carriage driver, or an overtired buggy whip, the accident deprived us of many more years of soulful sculptures. When Warner was young, his parents couldn't afford to pay for an art education for him, so he worked as a telegraph operator before embarking on a career in art, which yielded dozens of beautiful works, which you can view on the Smithsonian website.

Chief Joseph (1840-1904), known to the Nez Perce people as Hinmatóoyalahtq’it, Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain, is one of the most iconic figures in the history of the U.S., representing the integrity of a people who have stewarded the land since time immemorial. Warner's close friend, Charles Erskine Scott Wood, was present as a soldier at the surrender of Hinmatóoyalahtq’it to the U.S. military. Because, in Wood's words, "the speeches of Indians were not considered of importance," "no one was interested" to write down the speech except for Wood, who gave his recorded version to the Adjutant General of the Army in Washington, where disappeared. Controversy continues to this day as to the accuracy of Wood's text, especially given that Hinmatóoyalahtq’it didn't speak English. Wood, a poet and political organizer, saw in Hinmatóoyalahtq’it an opportunity for fame and fortune.

In 1889, Wood invited Warner to Portland, Oregon, where he introduced him to Hinmatóoyalahtq’it, who sat for Warner's sketches. If Warner stayed in touch, what was Hinmatóoyalahtq’it's response when Warner informed him that his image would feature in the bronze relief Tradition, above Warner's bronze doors on the exterior of the Library of Congress? I'd bet that he would have been indifferent to it, living the remainder of his life as a prisoner of war, while his face adorned the Library. For all of Warner's genius in sculpting, his brilliance in translating the Parisian sensibility of sculpture to the U.S., and his foresight in making medallions of members of several different indigenous nations, Tradition is awkward and embarrassing.

At the top of the relief, a very ancient-Roman-looking woman, evoking the tradition of the Romans to ascribe wisdom and other virtues to female deities, tells a story to a completely random assembly of people, including Hinmatóoyalahtq’it, an anonymous Viking, and a caveman. Tradition is beautiful to look at but, as a form of storytelling, it's incoherent. Let's hope for Warner's sake that he needed the money, and the concept was the brainchild of some politician who insisted on the absurd idea. "You won't be disappointed, sir," the sculptor would have said to a muttonchop-wearing congressman as he shoehorned the image of Hinmatóoyalahtq’it into the relief.

The strangest thing about Tradition is the lack of translators in the image: none of the figures would have spoken the same language. Even if you hang out at the Ren Faire dunk tank all day, you aren't likely to find a good Old Norse translator for our Viking. And according to my research, Phil Hartman's "Unfrozen Cave Man Lawyer" and the Geico Caveman, are the only cavemen who are fluent in English. Maybe the cavewomen translated for them.

Sources

- Morrissey, Katherine G. Mental Territories: Mapping the Inland Empire. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997.

- Thomas, Mike. You Might Remember Me: The Life and Times of Phil Hartman. New York: MacMillan, 2014.

- Tolles, Thayer, and Thomas Brent Smith. The American West in Bronze, 1850-1925. New York: The Met, 2013.

- "[U.S. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. "Imagination" and "Memory" bronze doors by Olin L. Warner]." Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.31984/.

- Venn, George. "Chief Joseph's 'Surrender Speech' as a Literary Text." Oregon English Journal 20 (1998): 69-73.

- "Olin Levi Warner." Smithsonian American Art Museum, https://americanart.si.edu/artist/olin-levi-warner-5240.

- Winick, Stephen. "'Oral Tradition' on the Walls of the Jefferson Building, Library of Congress, Jul. 28, 2016." https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2016/07/oral-tradition-on-the-walls-of-t….

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Olin Levi Warner

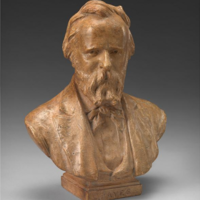

Olin Levi Warner (April 9, 1844 – August 14, 1896) was an American sculptor and artist noted for the striking bas relief portrait medallions and busts he created in the late 19th century.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Olin Levi Warner