More about Anne Whitney

Works by Anne Whitney

Contributor

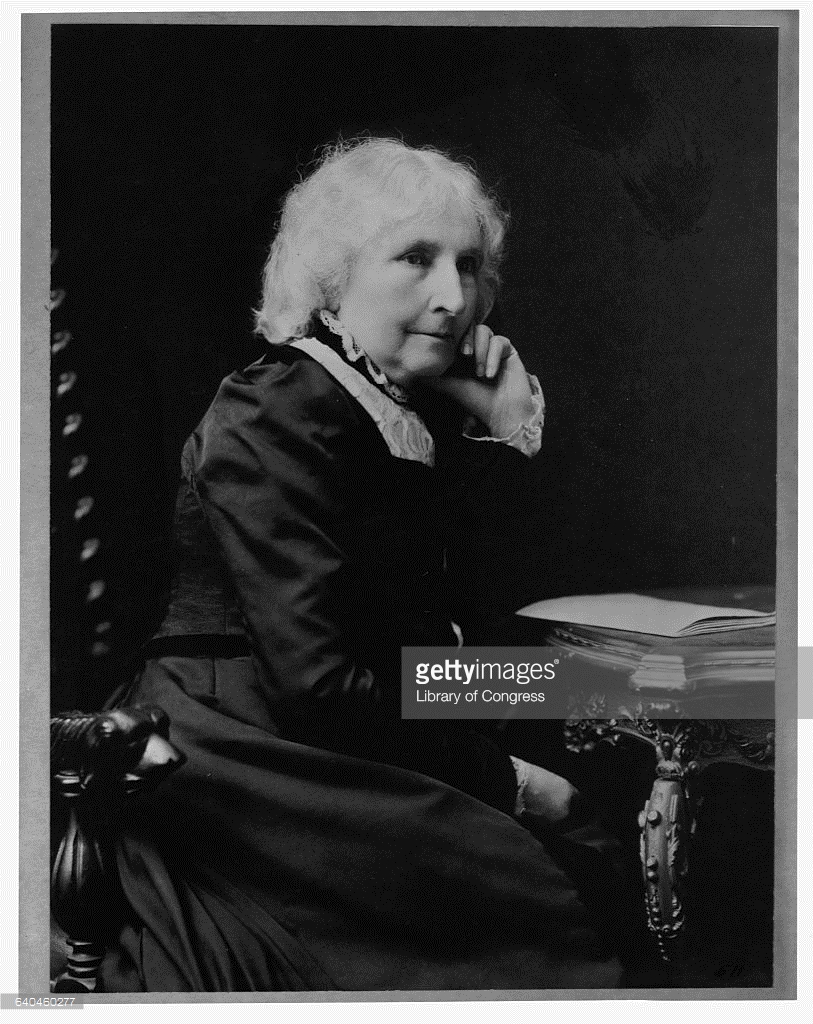

Anne Whitney was sick and tired of hearing what women should and shouldn’t do.

Scandalous for her sinfully short hair and independent lifestyle, Whitney didn’t let the naysayers steer her off course from the social commentary of her award-winning art. Impassioned by the movements of the suffragettes and abolitionists, Whitney always made a splash with her grandiose sculptures. Her favorite hobby? Working from her Boston home to become a sculptor twice as good and half as well-received as her male counterparts. Thanks, Victorian sexism!

Unfortunately, if this socially-savvy attitude sounds too good to be true, it’s because it is. Although Whitney was quite the forward thinker in terms of female voting rights and the necessity of abolition, her extensive letters reveal that she bought into the stereotypes of the day regarding Africans, Italians, Jews, and other ethnic groups. Although her prejudices were common for the accursed Victorian era, she should have been a better self-evaluator considering the ridiculous limits imposed on her art due to her gender.

By far the most aggravating instance of blind sexism in Anne Whitney’s lifetime came from the Boston Art Committee after she entered a sculpture competition. Whitney’s design of a sitting Charles Sumner, honored for his work in abolition, was initially awarded first place. Even though Sumner himself wanted her to have the job, committee members backpedaled when they discovered Whitney’s gender. Whitney’s award was revoked. In a suspiciously moronic attempt to save face, it was announced that women lacked the crucial ability to recreate the glory of men’s legs. A ridiculous assertion, really, since most of Whitney’s statues look quite proportionate. Take a look at those suspicious breasts on Michelangelo’s Night if you want to see awkward body parts.

Whitney’s lifelong partner was Abby Adeline Manning. Sharing a so-called “Boston marriage,” the two artists owned a home together and traveled to Europe. Whitney was especially drawn to the art scene in Rome. A sculptor needs models, after all, and pesky American prudishness prevented women from observing men in their birthday suits. Whitney had also received harsh reviews from a critic who said she “should go to Europe and learn what is required of a sculptor.” Ouch. Unfortunately for Whitney, once she’d made her way across the Atlantic, she committed a bit of a faux pas. Her sculpture Roma depicted the city as a poor old woman. Whitney’s work may have been banned locally, but it did make a stir in American exhibitions.

After Whitney’s death, her sister would ensure that she was buried next to Addy Manning. She’d left behind a sizable legacy, including published poetry and sculptures featured in the Smithsonian, the Harvard Art Museums, and all over the US. Not too shabby for a supposedly incompetent leg-sculptor.

Sources

- “Anne Whitney.” Wikipedia. May 30, 2017. Accessed June 8, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne_Whitney.

- “Anne Whitney.” History of American Women. Accessed June 8, 2017. http://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2015/06/anne-whitney.html.

- Musacchio, Jacqueline Marie. "Mapping the “White, Marmorean Flock”: Anne Whitney Abroad, 1867–1868." Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 13, no. 2 (2014). Accessed June 8, 2017. http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn14/musacchio-anne-whitney-abroad.

Contributor

It's strange that more attention is not paid to the poet and sculptor Anne Whitney, whose work is a significant development in the history of art.

Whitney was youngest child of seven, born to an abolitionist, suffragist, and Unitarian family in Watertown, Massachusetts in 1821. She wrote of her hometown in her only book of poetry, inspired by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, and Mary Shelley, published in 1859: "Yonder, beyond our paling/ of ash, and elm, and oak,/ hangs soft on the purple distance/ a visible, brooding smoke."

Whitney's poetry and sculpture are remarkable, as well as her "Boston marriage" to the painter Adeline "Addy" Manning, the daughter of her brother's friend. The term "Boston marriage" is a reference to the Henry James novel The Bostonians (1885), in which the characters Olive and Verena form a financial and emotional partnership which prevents them from having to rely on men. Whitney and Manning's relationship lasted nearly fifty years, through the end of Manning's life, and the couple lived together beginning in 1876, seventeen years after they met, until 1906. As Whitney's lawyer explains in a letter to the Manning family cemetery, Whitney arranged her own burial right next to Manning, in the Manning family plot. But they were probably just friends.

The city of Rome, muse of her favorite poets, meant to Whitney the possibility of personal freedom from her restricted, repressed Victorian life, as women artists there were allowed to study anatomy in ways that were deemed "improper" in the United States (i.e., from live, nude models). She worked at a hospital in Brooklyn to acquire this forbidden anatomical knowledge. In one of the most embarrassing episodes of censorship of Whitney's work, an arts council loved her seated statue of the abolitionist Charles Sumner, but refused to install it after learning that a woman had sculpted the man's legs. So Whitney was thrilled when invited to Italy by sculptor Harriet Hosmer, who was from her hometown and called Whitney her "brother sculptor."

But the journey was long, Italy was writhing from political conflict, and Whitney was partly responsible for her elderly parents' well-being in the uncertain era of the Civil War. Abolitionist work was important to Whitney and her family, and she certainly couldn't aid those efforts from Europe. Still, the more she delayed her trip, the more delectable and enticing it became. "O for a pair of wings," she wrote Manning, "or an air balloon... [and] a piece of a gone century of art to work in!" After the release of her abolitionist plaster sculpture Africa, now lost, one art critic threw shade on Whitney, the kind of shade that must have stung as it went right along with the artist's own feelings: "Miss Whitney should go to Europe and learn what is required of a sculptor.”

Upon that review, Whitney finally got the nerve to cross "liquid barrier" of the Atlantic to reinvent herself in Italy, along with the thirty-year-old Manning. Her letters record the lengthy list of items necessary for the strenuous task of ocean travel: smelling salts, lemons to prevent sickness, hoods to keep her warm. The journey took 17 days and was arduous. Whitney wrote in a letter home, on her 14th day at sea, "We have been more or less miserable since the first sickness [which] lasted a couple of days."

For all of the detail of her voluminous correspondence maintained by Wellesley College, there's not much to give a sense of Whitney's working methods. We do know, however, that she worked in clay first, then made a plaster cast to preserve the work, and, if she had received a commission, gave the plaster to a marble carver or bronze caster for the final product.

Sources

- Howe, Julia Ward. Representative Women of New England. Boston: New England Historical Publishing Company, 1904.

- Letter from James Fenimore Cooper to Mount Auburn Cemetery. January 20, 1915, Mount Auburn Cemetery Archives.

- Letter from Anne Whitney to Addy Manning. September 11, 1860, WCA MSS 4, http://omeka.wellesley.edu/annewhitney.

- Letter from Sarah Whitney to Anne Whitney and Addy Manning. Begun June 2, 1867, WCA MSS 4.193, Wellesley, http://omeka.wellesley.edu/annewhitney/neatline/show/detail#records/299.

- Musacchio, Jacqueline Marie. "Mapping the ‘White, Marmorean Flock’: Anne Whitney Abroad, 1867-1868." Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 13 (2), 2014.

- Payne, Elizabeth Rogers. “Anne Whitney: Art and Social Justice.” The Massachusetts Review 12, no. 2 (Spring 1971): 245–260.

- Smith-Rosenberg, Carol. “The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations Between Women in Nineteenth-Century America.” Signs 1, no. 1 (Autumn 1975): 1–29.

- Straws, Jr. “From New York: The National Academy of Design—Conclusion, Sculpture.” Springfield Republican, August 5, 1865, 3.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Anne Whitney

Anne Whitney (September 2, 1821 – January 23, 1915) was an American sculptor and poet. She made full-length and bust sculptures of prominent political and historical figures, and her works are in major museums in the United States. She received prestigious commissions for monuments. Two statues of Samuel Adams were made by Whitney and are located in Washington, D.C.'s National Statuary Hall Collection and in front of Faneuil Hall in Boston. She also created two monuments to Leif Erikson.

Through her art, she expressed her liberal views regarding abolition, women's rights, and other social issues. Prominent historical figures are depicted in her sculptures, including Harriet Beecher Stowe. She portrayed women who lived ground-breaking lives as suffragists, professional artists, and non-traditional positions for women at the time, including noted economist and Wellesley College president Alice Freeman Palmer. Unusual for her era, she lived an unconventional, independent life and had a lifelong relationship with fellow artist, Abby Adeline Manning, with whom she lived and traveled to Europe.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Anne Whitney