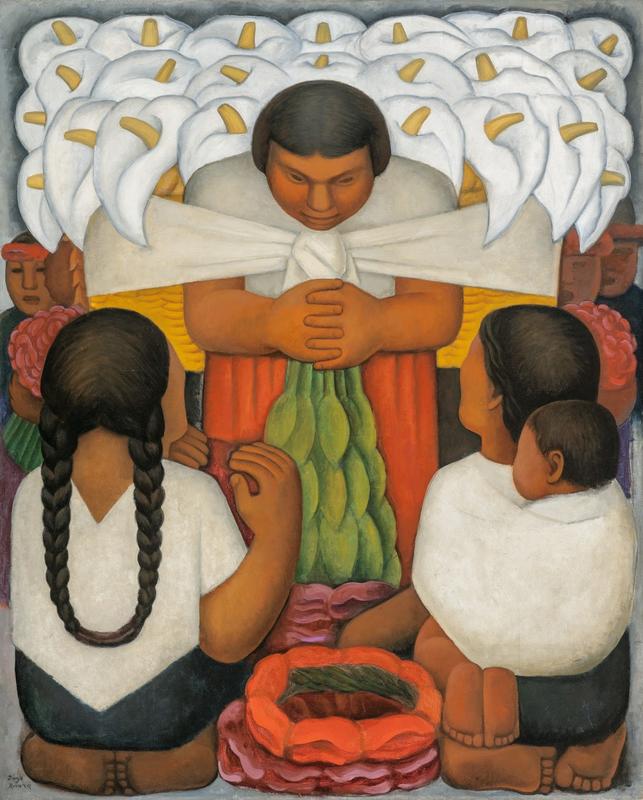

Diego Rivera’s Flower Day features beautiful flowers and strong figures to suggest the power of revolution and reform, even if he didn’t actually fight in the Mexican Revolution.

In fact, Rivera wasn’t anywhere near his native Mexico during the rebel uprising. Instead, he was gallivanting around Europe with other ex-pat artists like Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris. He was even Picasso’s neighbor in the trendy neighborhood of Montparnasse, France. But this didn’t stop him from using art as a means to communicate his radical, social agenda.

Living in such close quarters with these famous modernists while studying the art of the European greats gave Rivera’s art an interesting twist. He studied with the masters of Cubism but also infused his paintings with pre-Columbian art elements borrowed from the Aztec and Maya. Flower Day has the balanced composition of a Raphael altarpiece, the bold forms of a Cubist painting, and figures that celebrate native Mexican culture. Despite his training abroad, Rivera maintained a pretty specific MO, which was to raise international awareness of and appreciation for Mexican culture and history while championing the causes of the Mexican Revolution.

The Mexican Revolution increased this sense of political and cultural urgency for both artists and cultural leaders. During the revolution, Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa led a grassroots uprising of rebels that overthrew an oppressive dictatorship and installed a new, socially-conscious government. Although Rivera wasn’t a physical part of the revolution, he was on board with all of its social and political values. Rivera had been a Marxist his entire life, so the revolutionary labor reforms spoke to his Communist heart. His wife Frida Kahlo apparently also had a thing for Communists.

However, Rivera’s commitment to the revolution wasn’t so much physical as it was through his art. The revolution occurred between 1910 and 1920, and Rivera was in Europe until 1921. Much like David’s The Oath of the Horatii, Rivera did his part by creating an artistic celebration of revolutionary ideals, which he embodied in this and many other paintings of Mexican natives.

This scene of a calla lily vendor bowing to show off his wares is a subtle nod to the rebels of the revolution. Rivera renders the vendor in the red, white, and green of the Mexican flag. Additionally, Rivera’s stylized lilies look suspiciously like sombreros, which have a special place in Mexican heritage. To appeal to the Mexican sense of national pride, Zapata wore a sombrero and dressed like a charro, a traditional Mexican horseman, during the revolution.

This painting is chock full of hidden significance and meaning that resonated deeply with the contemporary, Mexican audience. LACMA also understood all that this painting stood for before LACMA was even a thing. LACMA’s precursor, The Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art, acquired the piece just after it won first place in the First Pan-American Exhibition of Oil Painting in 1925, putting both Mexico and the work’s promising young artist on the international stage.

With all these new plant parents, I think this would be a gorgeous addition to the greenhouse, are there prints available somewhere?