More about Mathew Benjamin Brady

- All

- Info

- Shop

Works by Mathew Benjamin Brady

Contributor

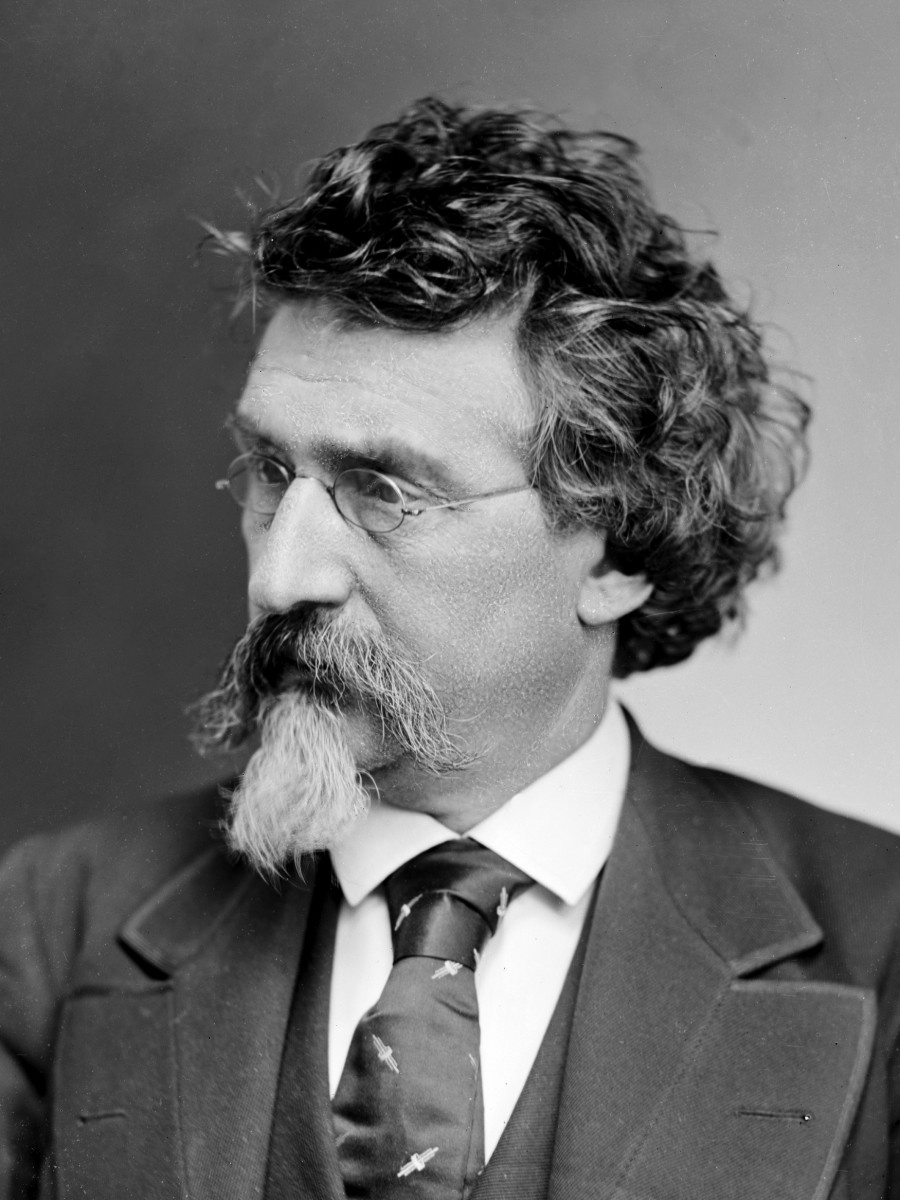

Mathew Brady pioneered the concept of war photography by single-handedly photographing the aftermath of battles during the Civil War.

And by “single-handedly,” we really mean “with a bunch of other people,” but Brady wouldn’t have wanted you to think of it that way.

Ever the entrepreneur, and after having learned everything he could from attending the first photography school in America (founded by Samuel F. B. Morse, the guy who invented Morse code), Brady first made a name for himself taking photographic portraits of famous Americans. Daniel Webster, Edgar Allan Poe, and James Fenimore Cooper were among them, but Brady also had an extensive collection of presidential portraits, including Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Grover Cleveland. (Pretty much everyone except William Henry Harrison, who died a month after his inauguration, so he barely counts anyway).

Once the Civil War broke out, Brady ambitiously decided he would document the bloodshed for its later historical value. The notion of war photography (let alone photography) was completely unheard of at this time, but Brady knew it would change the way Americans saw war forever. The U.S. government agreed to let him visit the battlefields, but would not pay for his expenses. Brady would have to take out loans personally.

“No problem,” said Brady, “There’s no way this could go wrong later!”

(Stay tuned for how it goes wrong later.)

In the meantime, Brady rounded up as many willing photographers as he could find to join his operation. While Brady himself did occasionally visit battlefields where these harrowing scenes were documented, he had overwhelming help from his dispatched photographers and assistants, preferring for the most part to organize and supervise the operation behind the scenes. Of course, this didn’t stop him from putting “Photo by Brady” over everything and misleading the public into thinking he took every single photo they saw. When some members of his team, including Alexander Gardner, protested that they should be given credit, Brady refused. Thus many men abandoned the project to pursue their own careers while Brady continued to write “Brady” on the caption of every photograph he could get his hands on.

After the war ended, Brady had spent about $100K on the whole operation. He figured, “NBD, the US government will obviously pay me back because they’ll obviously want these photographs that obviously document and preserve such an important moment in our country’s history obviously.”

(Here’s that part you were waiting for.)

Tragically, unforeseeably, Brady did not count on the government looking over all of his photographs and saying, “eh.” Brady ultimately had to file for bankruptcy.

Eventually some of his friends in politics convinced the War Department to buy his work, and Congress finally granted him $25,000, leaving him happily ever after, about $75,000 still in debt. He would never again regain financial solvency.

Towards the end of his life, Brady was in a traffic accident and broke his legs. He never fully recovered, and in 1896, the “father of photojournalism” succumbed to his injuries, alone and forgotten in a charity hospital. While we owe so much of our preservation of history to Mathew B. Brady, one can’t help but suppose he may have got his comeuppance for cutting everyone else out of his business. Still, the man could take a damn good portrait, and for that he will always be credited.

Sources

- American Battlefield Trust Editors. “Mathew Brady.” www.battlefields.org. Accessed June 7, 2018. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/mathew-brady

- Biography Editors. “Mathew B. Brady.” www.biography.com. Accessed June 7, 2018. https://www.biography.com/people/mathew-brady-9223725

- Encyclopaedia Britannica Editors. “Mathew Brady.” www.britannica.com. Accessed June 7, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mathew-Brady.

- Encyclopedia of World Biography Editors. "Mathew B. Brady." www.encyclopedia.com. Accessed June 7, 2018. http://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-…

- IPHF Editors. “Mathew B. Brady.” http://iphf.org. Accessed June 7, 2018. http://iphf.org/inductees/mathew-brady.

- Smith, Zoe C. "Brady, Mathew B". American National Biography. Accessed June 7, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1700096

Contributor

Hearing and reading about the Civil War, south of his successful early photography studios, Mathew B. Brady was seized by an indescribable, almost entirely irrational drive to bring his new art form, which was having a hard time asserting itself as "legitimate" art rather than just a cool new technology, to the front lines.

He would have to set up darkrooms on the battlefield, preventing the possibility of "action shots," he would be putting himself in harm's way, and ultimately, he'd be relying on the help of twenty-three other artists, but, as he recalled later, "A spirit in my feet said 'go,' and I went."

Going into battle with a white linen duster and straw hat, Brady, who had somehow inserted a "B" as the middle initial of his name, which doesn't stand for anything, was an unusual figure. He was inspired, and motivated, by the photographs of the Crimean War from about a decade earlier. His wagon, with all of his photography equipment, was called the "Whatsit" by Lincoln's soldiers, who didn't know he was taking photographs. Of the one hundred photos of Lincoln, almost a third are Brady's. He photographed Edgar Allan Poe, "Grant and Lee as well as Twain and Whitman and Dolley Madison and Daniel Webster." After winning, Lincoln said, "Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me President." I'm sure there are artists who can do things like that today, too, and I'm not talking about Kanye, but I'm not sure if there are politicians with that degree of humility. If there are, that's good news for us.

As a boy in Haudenosaunee country by the Canadian border, Brady had met William Page, a painter twelve years his senior, who was fascinated by the idea of a mystical union between humans and the Divine through self-identification with artworks. Page had given Brady crayons, and encouraged him to copy his paintings, later introducing him to the super-brilliant inventor Samuel B. Morse, who taught Brady photography in New York City. Morse, also the inventor of the telegraph, was, unfortunately, prone to conspiracy theories against immigrants and Catholics, and, rather than conceal his ancestry, Brady took this as an opportunity to use his skill for spinning a good yarn in order to survive and get along with his boss. They kept it profesh, and Brady became one of the greatest practitioners of the new, esoteric artistic technology. Morse was always annoyed that the most profitable form was portraits, or "face pictures," as he called them, and he yearned to prove to the world that photography was a legitimate medium on its own, for all kinds of images. Brady took up his mentor's desire.

Comparing Brady to a war widow, the poet Mary Ruefle writes,

He fell in love like a woman

in the folded arms

of a drying sweater:

touched one shoulder

and a whole platoon

was affixed with smiles.

Teeth already loose

falling from their envelopes

Sources

- Donlan, Leni. Mathew Brady: Photographing the Civil War. Chicago: Raintree, 2008.

- Garner, Dwight. "Magician of Light and Silver, Circa 1860." The New York Times, Aug. 7, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/08/books/mathew-brady-a-biography-by-ro….

- Meredith, Roy. Mr. Lincoln's Camera Man, Mathew B. Brady. New York: Dover, 1974.

- Murray, Stuart A. P. Mathew Brady: Photographer of Our Nation. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Ruefle, Mary. Memling's Veil. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1982.

- Trachtenberg, Alan. Reading American Photographs: Images As History-Mathew Brady to Walker Evans. New York: MacMillan, 1990.

- Wilson, Robert. Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Mathew Brady

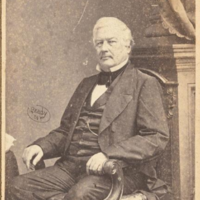

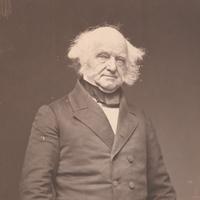

Mathew B. Brady (c. May 18, 1822 – January 15, 1896) was an American photographer. Known as one of the earliest and most famous photographers in American history, he is best known for his scenes of the American Civil War. He studied under inventor Samuel Morse, who pioneered the daguerreotype technique in America. Brady opened his own studio in New York City in 1844, and went on to photograph U.S. presidents John Quincy Adams, Abraham Lincoln, Millard Fillmore, Martin Van Buren, and other public figures.

When the Civil War began, Brady's use of a mobile studio and darkroom enabled thousands of vivid battlefield photographs to bring home the reality of war to the public. He also photographed generals and politicians on both sides of the conflict, though most of these were taken by his assistants rather than by Brady himself.

After the end of the Civil War, these pictures went out of fashion, and the government did not purchase the master copies as he had anticipated. Brady's fortunes declined sharply, and he died in debt.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Mathew Brady