More about Berenice Abbott

- All

- Info

- Shop

Works by Berenice Abbott

Sr. Contributor

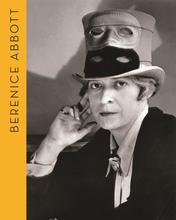

Berenice Abbott wasn’t interested in being a boring “nice girl.” She was interested in making a name for herself in the realm of photography.

Like most great artists in the early 20th century, Berenice Abbott left the United States to study art in Europe. Nothing against the good ol’ U.S. of A, but the country just wasn’t “there” yet in terms of the arts. So, like every other painfully hip artist at the time, Abbott spent the 1920s in Paris, working and absorbing the latest in artistic styles. During her stint abroad, she served as a dark room assistant to the infamously experimental and strange Man Ray, who pushed the medium of photography to its limits, even in its earliest stages.

In 1929, the former expat decided to return to New York and show off her newfound photography skills. This time, she began taking pictures of the urban jungle, fascinated by the landscape of skyscrapers, bridges, and people. She especially wanted to capture what she saw in a straightforward and objective way. For Berenice Abbott, what you see is what you get – definitely not like those unnecessarily artsy photographers like Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen whose photographs approached abstraction. What nonsense.

To capture her impressive architectural shots she had to boldly go where no women had gone before. Like a more modern version of Rosa Bonheur, Abbott was brave enough to do things that were considered “unladylike” and were definitely frowned upon. An older man reportedly warned her against going down to the rough and tumble area of Manhattan’s Bowery, where Martha Rosler later made a fantastic photo series, saying that it wasn’t a place for “nice girls.” Ever the badass, Abbott responded, “I’m not a nice girl. I’m a photographer. I go anywhere.”

Berenice Abbott was okay with not fitting any prescribed molds. I guess that’s not how greatness is born. She was a teacher, author of nearly a dozen books, and even an inventor who held four patents for inventions that aided the photographic process. Always the innovator, Abbott had the great idea to use photography to capture what the naked eye couldn’t see. Her science photography became popular, and in 1944, she became the photographic editor of Science Illustrated. Taking pictures of the path in which a ball bounces and illustrating what a magnetic field looks like, she captured the elusive beauty of physics. Her photographs adorned the pages of a high school physics textbook that millions of Americans read in school.

She also had some unconventional political views. In the midst of the Cold War, Abbott was a Communist sympathizer – so much so that the FBI started a file to keep tabs on her in 1951. Although she may not have been as hardcore as Frida Kahlo was with her love for Joseph Stalin, Abbott wasn’t exactly secretive about her unpopular opinions. She remained a fan of the party well into the 1980s and was openly sad to see the Soviet Union fall just before her death in 1991.

Today her photographs are especially interesting, as many of the buildings that star in her images have been demolished to make way for the next generation of skyscrapers.

Sources

- Hirsch, Robert. Seizing the Light: A History of Photography. Boston: The McGraw-Hill Companies, 2000.

- Newhall, Beaumont. The History of Photography. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1982.

- O’Hagan, Sean. “Berenice Abbott: the photography trailblazer who had supersight.” The Guardian. Culture. March 10, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/mar/10/berenice-abbott-sc…. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- Solomon, Deborah. “Berenice Abbott: She Was a Camera.” The New York Times. Reviews. June 1, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/01/books/review/berenice-abbott-julia-v…. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- Van Haaften, Julia. “Not a Nice Girl: On Berenice Abbott.” The Paris Review. April 10, 2018. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/04/10/not-a-nice-girl-on-beren…. Accessed August 20, 2018.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Berenice Abbott

Berenice Alice Abbott (July 17, 1898 – December 9, 1991) was an American photographer best known for her portraits of cultural figures of the interwar period, New York City photographs of architecture and urban design of the 1930s, and science interpretation of the 1940s to the 1960s.

Super Sight, also known as the Abbott Process, is a form of macro photography developed in the early 1940s by Berenice Abbott.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Berenice Abbott