More about St. Dionysus

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

Kehinde Wiley’s St. Dionysus juxtaposes black masculinity with a classical art background.

You might recognize Kehinde Wiley’s name as the artist who painted President Obama’s official portrait. It was in the news because it was different than any presidential portrait we’d seen before, in part because Obama was different than any president we’d had before. Wiley’s signature juxtaposition of his central figure and a vibrant patterned background is consistent, but Obama was the biggest name to take center stage in one of his paintings.

Before the Obama portrait, Wiley made a name for himself by combining old classical sensibilities to modern subjects. The clash of the two is often jarring, but always powerful. Let’s face it, while they hold so much historical weight, the classics can often be boring. Not for the lack of craft or care that went into their creation, but for the sheer fact that they are incredibly narrow in their subject matter. And we’ve evolved so much creatively since then. To the average viewer, they may simply seem basic. But at the same time, classic works of art are still held in high regard. We still learn about artists who lived hundreds of years ago because of the precedence that they and their work set. And no matter what we think about them, they still stand out to us at the very least because they feel familiar.

That’s what Kehinde Wiley is trying to tap into; that familiarity. There’s something about his art that feels recognizable. And once it brings you in, it introduces you to something else entirely. St. Dionysus is the perfect example of this. Its title and background suggest a painting of old, but its subject and popping colors tell a different story. One we need to listen to. Wiley’s paintings are without a doubt contributing to the Identity Politics category of art, which basically means that his work focuses on those with which he identifies, in a way to uplift them and put them into the forefront. And he’s talked about how being immortalized in a portrait is a sign of power. Think about it, all those historical portraits that you learned about in school were always Kings, Queens, and religious leaders. But is it the subject of the portrait, or the status that a portrait conveys that really represents the power? Mixing unfamiliar with the familiar is Wiley’s attempt to give a platform to those who’ve been denied that power.

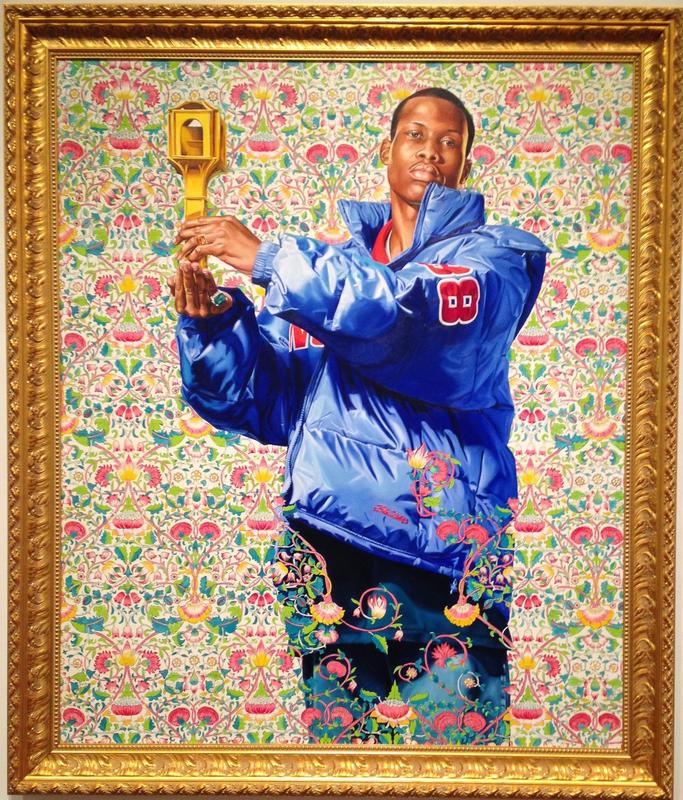

Walking up to St. Dionysus at the Milwaukee Art Museum, you’d naturally look at the plaque in front of the painting to get some information. That name might strike you as archaic. Maybe this is a portrait of an old Greek bishop, like the one you learned about in your World History class who claimed he saw a solar eclipse the day that Jesus died. But then you look up and see a young black man, in a puffy sports coat staring back at you. This doesn’t resemble the Saint you learned about in school at all, but the longer you look at it, the more this man looks like he belongs, despite what you were expecting.

In a critique of Wiley’s larger works, research associate at the Brooklyn Museum Connie H. Choi writes, “In inserting the urban black male figure into the art-historical canon, the artist brings the canon up to date and at the same time questions its centuries-long exclusion of such figures. His manner of portraying African American men is Wiley’s way of affirming their presence in a society that has long discounted or undervalued them.” The pink and green patterns are reminiscent to something you might see in an old church or a palace that housed important monarchal figures. And then we’ve got the subject of the painting, who looks like he just walked out of a Detroit Pistons game from 2004. The marriage of the two is when the patterns seem to both simultaneously enwrap and open up for Dionysus to be on display for any onlookers-- both accepting him and putting him on display.

The story behind how the subject of the painting became the subject is indicative of just how much Wiley cares about who he gives the spotlight to. "I remember it like it was yesterday," says WNYC's Darnell Jefferson. Back in 2005, he answered an ad on Craigslist where Wiley was seeking a model to pose for him for St. Dionysus. "I remember wearing that blue bubble coat, with that crown — I was probably 24 years old when I did that portrait with him."

Wiley wasn’t looking for someone we would consider recognizable. He wanted someone who people often overlook. That way when they see the final product, they can ask themselves why this feels different from anything they’ve ever seen before. For some people, that will mean confronting history’s role of erasing certain types of folks from the narrative, and to others it’ll mean that they get to see themselves represented in a space and a medium that has purposefully forgotten them.

Sources

- Jeantly, Diane. “When You Find Out Your Coworker Was Painted by Obama's Portraitist.” WNYC News. February 15, 2018. https://www.wnyc.org/story/when-you-find-out-your-coworker-was-painted-…

- Jones, Emily Victoria. “Christian-themed portraits by Kehinde Wiley” Art & Theology. August 31, 2016. https://artandtheology.org/2016/08/31/christian-themed-portraits-by-keh…

- Orthodox Church in America. “Hieromartyr Dionysius the Areopagite, Bishop of Athens.” Accessed November 21, 2019. https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2019/10/03/102843-hieromartyr-dionysiu…

- Tanzilo, Bobby. “Obama portrait artist has Wisconsin connections, including a work at MAM.” On Milwaukee. February 19th, 2018 https://onmilwaukee.com/ent/articles/kehinde-wiley-milwaukee-art-museum…

- The Art Story. “Kehinde Wiley.” Accessed November 21, 2019. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/wiley-kehinde/