More about Still life with Plaster Cupid

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

Even though everything seems a bit askew, Cézanne wasn’t drunk or painting with one eye closed when he made this composition. He actually wanted his paintings to look like this.

All jokes aside, Cézanne is so important that he has his own chapter in pretty much every book on art. Cézanne infamously broke the rules of art with reckless abandon, daring anyone who had something to say to take him on. The most egregiously modern aspect is Cézanne’s denial of any sense of spatial depth. Cézanne simply decided that one and two-point perspectives were so last century. Why not go for five or six points from which to view an object? In doing so, he completely collapsed his paintings into flattened funhouses. It was the strongest rejection of the spatial illusions since the discovery of perspective itself during the Renaissance, and you better believe Cézanne wore it well.

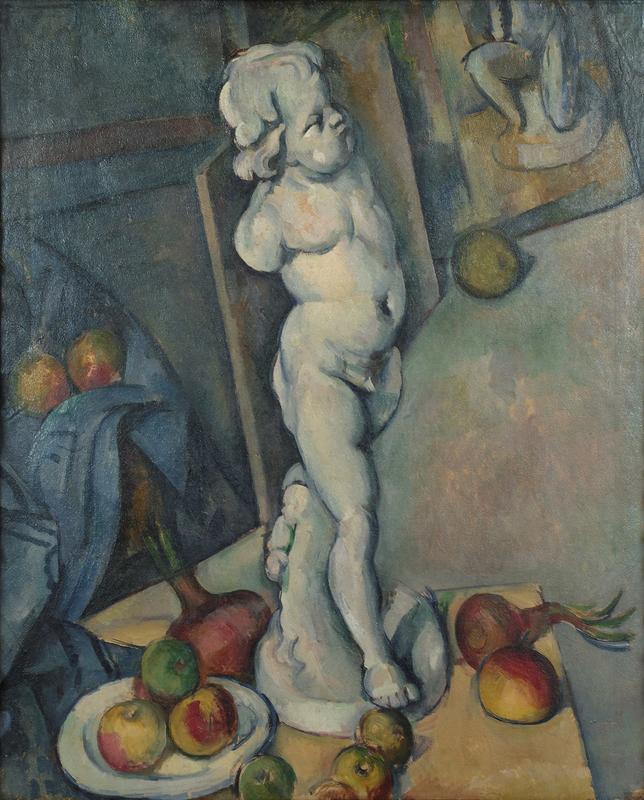

Cézanne’s approach is admittedly jarring, and I definitely feel a bit of motion sickness at first glance. Despite his quest to render any subject with “complete accuracy,” his paintings are remarkably off-kilter and always look a bit – incorrect. But in their wrongness lies the secret to Cézanne’s genius. He sought to represent the process of looking as it happens in real time. Cézanne was illustrating how a person inevitably looks at something from multiple angles to get a true understanding of an object or a scene. After this revelation, Cézanne began to paint a subject as seen from two different angles. By the time he got to Still Life with Plaster Cupid, he was toying with even more perspectives.

Cézanne’s clever approach might have us question, “What even is reality, man?” quicker than someone who has smoked a bit too much of the good stuff. Nevertheless, he took to the still life genre to answer this question. Once considered one of the lowest forms of painting, still life formerly belonged to the realm of women like Clara Peeters and Rachel Ruysch, who were relegated to this lesser genre due to their gender. Where these women flourished, so did Cézanne, and the still life ultimately became central to his work.

Here, Cézanne uses the representation of other artworks to question the very nature of art itself. Alongside his own paintings of fruit, he has the plaster cupid, which is a seventeenth-century Baroque statue. In the background, there’s also another painting of an entirely different statue. Coupled with the distortion of the space in which all this craziness unfolds, Cézanne establishes a delicate balance between reality and illusion. If you look closely, you can see a lone onion traversing the boundary that separates the two worlds Cézanne has created in this painting.

Sources

- Art and Architecture. “Still life with plaster cupid.” Image. http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/gallery/872882ac.html. Accessed 20 April 2020.

- Courtauld Institute. “Paul Cezanne’s Still Life with Plaster Cupid,” YouTube, 1 July 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0xx97BBPAY8 (accessed 20 April 2020).

- Gompertz, Will. What Are You Looking At? New York: Penguin Group, 2013.

- Khan Academy. “Cezanne, Still Life with Plaster Cupid.” Arts and Humanities. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-fran…. Accessed 20 April 2020.