More about The Last of the Buffalo

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

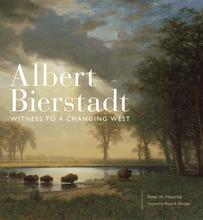

Before painting the buffalo apocalypse, Albert Bierstadt made a living depicting America as a magical place with serene mountainscapes and pretty flowers.

Bierstadt was the first major landscape painter to be able to see the American West. His work became a sort of medium for many Americans to experience the region without having actually gone there—a service he was more than happy to provide, at first. The guy was all about marketing: private screenings, ticketed events, curtains, dark rooms, popcorn (probably), the works.

To top off all the pageantry, Bierstadt’s paintings themselves were known for being really dramatic and artificial. Everything was a paradise with green grass and gorgeous mountains and perfect lighting. In his hands, the American West was a place as beautiful as it was soft and cushy.

But things changed when people began flocking to the West, partly because of just how nice Bierstadt had made it seem over there. As the frontier became settled, Native Americans were forced from their homes and put onto reservations, hunters had driven the bison to almost complete extinction, and Bierstadt started to think he may not have been helping things so much. The Last of the Buffalo is his way of saying: my bad, guys.

Bierstadt knew he was a big part of the problem—he was a former hunter who had joined and supported many extravagant hunting expeditions across the West. Only seven years before painting Buffalo, he had visited Yellowstone National Park (the park was still less than a decade old) and shot a bunch of animals illegally, just, you know, because. The dude was known as “paragon of game ravagers” among hunter circles, which just sort of means he killed way more animals than his friends did.

Yet somewhere along the line Bierstadt started to feel bad. He witnessed America change before his eyes and when the bison population plummeted, he implored Americans to take wildlife preservation seriously and protect the bison species from extinction. He even joined the Boone and Crockett Club, America’s first conservation organization, and painted Buffalo in the spirit of their meetings and the movement they stood behind. Talk about a change of heart!

Some critics thought he was trying to blame the loss on Native Americans (people Bierstadt claimed to love dearly). The painter insisted his work should to be read allegorically, AKA it’s all a metaphor, man. It’s not about literal bison or literal Native Americans, it’s about the loss they figuratively represent, you know? But also like it was actually about the bison, too.

Something happened to Bierstadt—maybe it was indeed the displacement of Native Americans or maybe it was the dwindling bison population. Maybe it was the fact that his studio in New York burned down a few years earlier or that his wife was dying from consumption—whatever it was, Bierstadt became fixated on loss and conservation. This painting was the last dramatic oil painting of the West he ever made. A year later, the National Zoo was established and live bison had been brought there in an effort to follow through with America’s new conservation mission. So there you go—one of the reasons we even still have bison roaming around the country now is because of our dramatic oil painter friend here. Thanks, Bierstadt!

Sources

- Brenson, Michael. "Reviews/Art; He Painted the West That America Wanted." The New York Times, February 8, 1991. http://www.nytimes.com/1991/02/08/arts/reviews-art-he-painted-the-west-….

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bierstadt, Albert". Encyclopædia Britannica. Cambridge University Press.

- Heydt, Mayer. "Bierstadt, Bison, and the Birth of a Western Concept." In Art of the American Frontier. The Buffalo Bill Center of the West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

- National Gallery of Art Editors. "The Last of the Buffalo." National Gallery of Art. Accessed October 20, 2017. https://www.nga.gov/Collection/art-object-page.124525.html.

- Smithsonian National Museum of American Art. National Museum of American Art: Smithsonian Institution. Washington, D.C.: Museum, 1995.

- Wimmer, Maria. "Albert Bierstadt: Landscapes of the American West." Wyohistory.org. Accessed October 20, 2017. https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/albert-bierstadt-landscapes-ame…