More about Self-Portrait

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

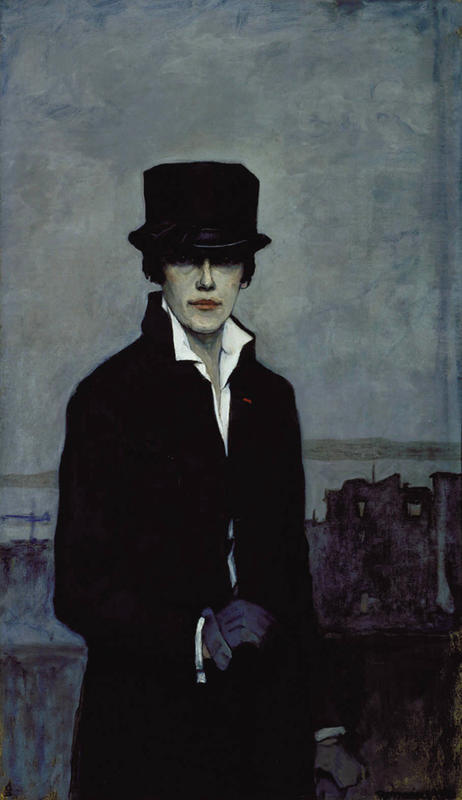

Dressed like a “dandy” and staring confidently out of the canvas, Romaine Brooks dares the viewer to question gender, sexuality, and the possibilities for women.

In the foreword to Amazons in the Drawing Room, National Museum of Women in the Arts director Nancy Risque Rohrbach (what a name!) writes, “Romaine Brooks’s stunning psychological portraits provide a significant record of European literary and artistic culture from 1910-1930.” This tells us so much worth knowing about the artist. She’s celebrated by feminists across history. She was tapped into a rich creative network of edgy people, mostly women, from a particularly intriguing historical era. And you can see the psychology of the people she painted within her works.

She took no less care with her 1923 Self Portrait than she did when capturing the minds of other models on her canvas. Just a glance at this work tells us even more about her. Painted nearly 100 years ago, long before we had genderfluid language, she has depicted herself wearing masculine clothing, tailored like a man’s would be, in dark tones. This polyamorous lesbian wasn’t shy about her androgyny; she stares straight at the viewer with bold confidence. It represents her entire view of herself as an artist and how she challenged the world to see her in the same way. It’s particularly brave work when you consider that at the time there were very few examples of lesbian style or signifiers of that subculture. She has turned to the attire of the gay male “dandy” to represent gay female sexuality in a new light. This work launched a series she did of strong women in similar clothing, effectively telling the world, “we’re here, we’re queer” long before such a phrase entered common verncaular.

When you look at reproductions of the work, particularly online, you don’t really get a sense of the striking power of her eyes. They’re strategically hidden under the brim of her hat. However, if you see the painting in person, you discover that the eyes gaze directly out at you with bold alertness in a way that has been described as startling. One critic argued that it’s as though she’s intentionally sizing you up before you get close to her, deciding whether or not you are worth her time.

Three intriguing things greatly impacted the work that Brooks chose to create and we see them clearly in this painting: 1) She came from wealth so she was able to run in circles that might otherwise have been unavailable to her. 2) She had an abusive childhood that certainly led her to an interest in the psychology of life and relationships. 3) Her homosexuality was a critical part of her work and life, inevitably tied up in her creative process.

Since she came from money, she could pick and choose who she wanted to model for her. She did so judiciously. She didn’t have to make a living from her art since she inherited her mother’s money upon the abusive woman’s death. Therefore, she could give all of her intention to her creative impulses, choosing only those subjects that interested her most. She liked people with flair and personality and unique takes on life. It’s no wonder that she was one of her own best subjects. She created several different self-portraits over the years, in multiple mediums; this one depicts her nearing age 50. That’s just another example of how daring she was, a woman seemingly unafraid to age under the public gaze.

This Self Portrait speaks volumes on its own, but it is when shown alongside other works in themed exhibitions that it really shines. In 1979, it hung in an exhibition of 61 works titled “As We See Ourselves: Artists’ Self‐Portraits” at the Heckscher Museum where it sat alongside works by Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning, demonstrating what a range of different types of women artists thrived in the first half of the 20th century. In 2011, it hung at the Brooklyn Museum in “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture,” which was a collection of portraits and self-portraits from 20th century gay artists. It sat there alongside photographer Bernice Abbott’s 1927 portraits of writer Janet Flanner and art dealer Betty Parsons, highlighting the creative lesbian elite of the era.

In other words, this work is an example of how a self-portrait can be not just a picture of the person in the image or even a telling story about the artist herself but can also provide important insight into the social, cultural, and political aspects of an entire era in history. Brooks was an outstanding woman who helped pave the way for a new voice for homosexual, androgynous women in the early 20th century; this painting is a record of that important work.

It’s critical that we return again and again to view works like this through the new social understandings we’ve gained over the years, especially as we’ve gone back to review history with a critical eye, knowing as we do now that it was told through the lens of a white male gaze and must be revisited in order to see the truth. In a 1979 article, it is said that her Self Portrait paints her as a victim, living a life in which lesbianism was viewed as only marginally more acceptable than cannibalism. Revisited in the 21st century, the painting is rewritten as a powerful statement of self-confidence and a striking example of a real woman who differed from the caricature stereotypes of the flapper era. Thanks in no small part to her wealth and status, Brooks’ work was recognized in its time. This painting was shown in at least half a dozen major publications in America and France. And yet, as the edgy 20s faded into the domestic 40s and 50s, history seemed to favor her more as an outcast than an innovator. Thankfully, she’s resurged into new awareness in recent years, and we can see Self Portrait for the brave work that it is.

This article has an amazon affiliate link, meaning that at no additional cost to you, by clicking through and making a purchase, you will also be contributing to the growth of Sartle.

Sources

- Chadwick, Whitney et al. “Amazons in the Drawing Room: The Art of Romaine Brooks.” University of California Press. 2000.

- Cotter, Holland. “ART REVIEW; Politics Runs Through More Than Campaigns.” The New York Times. Aug 25., 200. Retrieved June 25, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/2000/08/25/arts/art-review-politics-runs-throug…

- Latimer, Tirza True. “Romaine Brooks and the Future of Sapphic Modernity.” Sapphic Modernities: Sexuality, Women, and Natural Culture. 2006. Springer.

- Lucchesi, Joe. “The Dandy In Me: Romaine Brooks’s 1923 Portraits.” Dandies: Fashion and Finesse in Art and Culture. 2001. NYU Press.

- Russell, John. “Art: Self-Portraits at L.I.’s Hecksher.” The New York Times. Jul. 13, 1979. Retrieved June 25, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/1979/07/13/archives/art-selfportraits-at-lis-he…

- Smith Roberta. “This Gay American Life, in Code or in Your Face.” The New York Times. Nov. 17, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/18/arts/design/hide-seek-portraits-at-t…