More about Emile Zola

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

Emile Zola is revered as one of the fathers of naturalistic literature, but at the time people were interested in one thing: Sex, sex, sex!

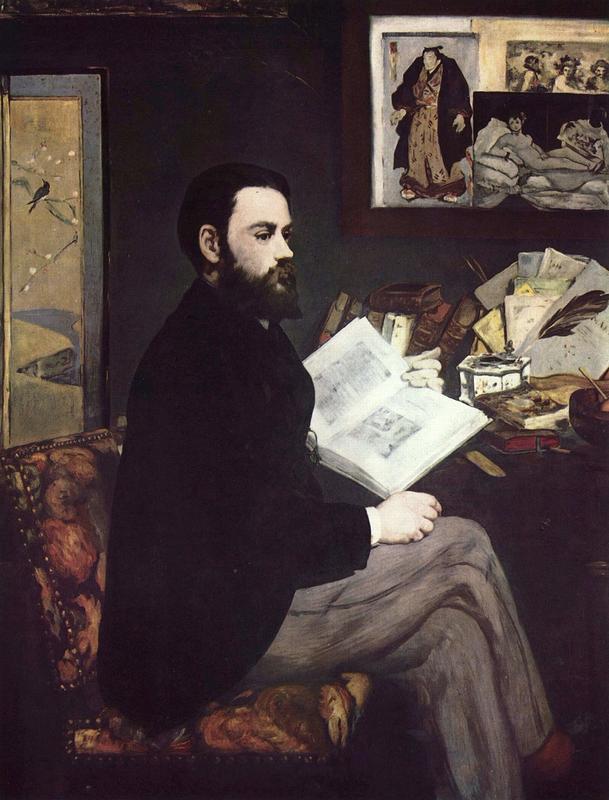

When this was painted, Zola was still glowing from the success of his salacious novel Therese Raquin, about a torrid affair between a married woman and a young artist who is misunderstood by the critics (coincidence?). Zola based a scene in the book on Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, and also modeled the main character in his novel Claude Lantier after Manet. Zola later wrote Nana, the sexual adventures of a prostitute, which became a #1 bestseller after a sensational publicity campaign...sort of the Fifty Shades of Grey of its time. Manet painted an illustration of the title character in her undies.

Zola, Manet and Paul Cezanne were all buddies from way back, and Zola was a fierce defender of Manet against the critical outrage over Olympia and Luncheon on the Grass. Manet painted this to say thanks (note to self: do favor for brilliant artist). Manet includes a reproduction of Olympia in the background, a reference to Zola having his back in the scandal, and because it was Zola’s favorite of his paintings. A purely academic choice of course; Olympia’s perky bosoms had nothing to do with it.

An etching of Velazquez, a Japanese print, and Japanese screen also appear in the background. Manet was profoundly influenced by Velazquez’ loose yet hyper-realistic style and by the color palette of Japanese art. Orientalism was all the rage. Japan had just opened its borders to foreign trade for the first time in hundreds of years, and cultural appropriation was the new black.

Zola went on to bigger things than softcore porn, such as his social activism against anti-semitism. His most famous cause was the notorious Dreyfus Affair, in which a Jewish military officer was wrongfully convicted of treason and imprisoned on Devil’s Island. Zola devoted the last decade of his life to exonerating Dreyfus, with tragic consequences. Zola was killed by carbon monoxide poisoning after his bedroom flue mysteriously closed while a fire was burning. The death was officially ruled an accident, but Zola’s mistress Jeanne insisted it was murder. Pro-Dreyfus propaganda proclaimed that the right wing establishment assassinated Zola, while anti-Dreyfus propaganda claimed Zola committed suicide when he found proof that Dreyfus was guilty. A roofer later confessed on his deathbed that he had closed the flue deliberately to assassinate Zola.

Paul Muni played him in the film The Life of Emile Zola (1937), winner of three Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Actor. Vladimir Sokoloff played Cezanne. Unfortunately, no Manet in this one.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Portrait of Emile Zola

Portrait of Émile Zola is a painting of Émile Zola by Édouard Manet. Manet submitted the portrait to the 1868 Salon.

At this time Zola was known for his art criticism, and perhaps particularly as the writer of the novel Thérèse Raquin. This told the story of an adulterous affair between Thérèse, the wife of a clerk in a railway company, and a would-be painter named Laurent, whose work, rather like that of Zola's friend Paul Cézanne, is denigrated by the critics. In the eleventh chapter the milieu of Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe is evoked, in the murder scene, where Camille, the husband, goes out for the day with his wife and her lover to Saint-Ouen.

On the wall is a reproduction of Manet's Olympia, a controversial painting at the 1865 Salon but which Zola considered Manet's best work. "Behind it is an engraving from Velazquez's Bacchus indicating the taste for Spanish art shared by the painter and the writer. A Japanese print of a wrestler by Utagawa Kuniaki II completes the décor." A Japanese screen on the left of the picture recalls the role that the Far East played in revolutionizing ideas on perspective and colour in European painting.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Portrait of Emile Zola